Blog Archives

Seeking Darkness

.

.

In a blog post from last September, I wrote how I felt like I was ‘chasing light’ by hopping from summer in the northern hemisphere to catch another summer in New Zealand, only after doing similar hemisphere-hopping travels the year prior. Now, back in the northern hemisphere, we have recently passed the summer solstice—the day with the most light each year. For me, this marks five summer solstices in a row without experiencing a winter solstice. I, indeed, have been chasing light.

But, in my hemisphere-hopping quest for summer light, I found myself inevitably pursuing just the opposite. After experiencing so many summers in a row, I ended up, quite literally, seeking darkness. Sometimes rather desperately.

The details were that I was following along a thru-hike in New Zealand. Te Araroa—New Zealand’s longest trail—which I tramped my way along from last October through February. Peak summertime in the southern hemisphere. Long summer days filled with ample sunshine in New Zealand’s high latitudes. And I was outside camping for all of it.

In spite of this, I began to seek out the darkness like a nocturnal animal. Though backpacking and camping itself are most practically done during daylight hours, my sleep schedule shifted to be more night-oriented. I was desperately craving the dark. Always an early-bird before, I instead felt the pull to become a night owl.

My daily hiking routine was far different from most other trampers. I would lollygag and nap my way through the afternoon’s hiking route—I never felt in a rush to get anywhere—and this resulted in a delayed arrival at the campsite or hut later in the evening. Daily chores of setting up camp and cooking dinner would take me even later into the evening hours. While nearly all my hiking compatriots would be in bed sleeping before sundown, I would continue to stay awake. At the fall of nighttime, I would feel a sense of relief. Reawakened, reinvigorated by the dark, I would remain conscious. I was enlivened again. Aside from a little bit of stargazing, seeking out glowworms, or swimming with bioluminescent algae, I tended to not explore much after dark. Instead, I cocooned. I would cozy up in my tent or in the hut. I would read or journal. Or, failing that, I would just lie awake and think. My mind was becoming clear and active. It was no time for sleep.

Delayed bedtimes from my nighttime activities resulted in delayed mornings. Late nights meant later waking times, and increasingly later starts to the hiking day. My daily routine of wake-hike-camp-sleep kept creeping later and later into the day. I got into an inefficient (by thru-hiker standards) pattern of waking around 10 or 11am, leaving camp by noon or later, and arriving at the next camp just before sundown (or, in some cases, after sunset). I started setting up my camp and cooking dinner exclusively by the wane light of a headlamp. And since I never wanted to go to sleep immediately after making camp, I continued to stay awake after dinner reading and journaling by the dim glow of a red light. The spiral of becoming more nocturnal continued.

Keeping this kind of sleep schedule meant that upon waking in the morning, nearly always everyone else at the huts or campsites had already departed. I would thus be greeted by a peaceful morning of blissful solitude in a beautiful location. Upon arriving at the next hut or campsite the following evening, I found most of its occupants would already be in bed, or pretty darn near to it. A direct result was that I started talking less and less to my fellow Te Araroa trampers. I became a temporal recluse. I embraced the quietness and seclusion that night offered, and I basked in this new-found introverted time.

In essence, I think what I was craving was not the darkness itself, but something that the dark provided. Nighttime can facilitate certain events and emotions that the daytime cannot do justice. Darkness sets a certain mood and ambiance, and that was what I had been craving for so long.

Summer seasons, with their long days and ample light, play host to social gatherings and long adventurous outings in the outdoors. Summer is an externally-focused season, with an emphasis on travel, exploration, and sociality. Winter seasons, in contrast, play host to a quieter, more subdued, more introspective disposition. The darkness closes off the self to much of one’s surroundings—the world becomes more limited, and the internal self begins to take focus. The snug coziness of one’s safe protected domicile on a dark winter’s day offers a feeling of security that cannot be matched by the bright and benign summer. From this position, one can look inwards at oneself, reflect, grow, introspect.

With so many summers in a row under my belt, I think my body and soul were craving that dark introspective rest period to relax and mentally digest all my recent experiences. Leading up to Te Araroa, I had undergone many long adventurous summer days of travel, socializing and exploration—a summer guiding canoe trips in the Boundary Waters, a summer working at a research station in Antarctica, an entire summer spent leading a backpacking trip on the arctic tundra of Alaska. Then to top it all off, I started on this long endeavor of a thru-hike on New Zealand’s longest trail. All this movement and exploration simply became too much for my own desires. Instead, I was craving a more relaxed pace—just to have some time to sit and process through everything I had done while the days were long and my thirst for adventure was high.

Personally, I find myself quite cognizant and responsive to the change in seasons. I grew up in a temperate climate. The places I call home are marked by a strong seasonality from summer into winter and back again. Furthermore, I have chosen to pursue a career as a seasonal worker in the outdoor industry, where the arc of my year follows the progression of the seasons—and I am outdoors witnessing the changes for most of it. In the temperate climates I call home, there is a distinct period of rapid growth and activity, followed by a period of rest and dormancy.

The plants in the temperate landscapes where I grew up have adapted to this seasonal cycle. In fact, many cannot live well or reproduce if the hard winter cycle is broken. Buds fail to open, flowers fail to bloom, seeds fail to germinate. The changes in the plants’ metabolism are triggered by changes in light and cold—processes known as cold stratification and vernalization. As a plant connoisseur, I am in-tune with the plants around me. And similar to the plants, I need these seasonal cycles for my own healthy biology.

There was only one other time in my life where I felt acutely the lack of change in seasons. It was the first time I had ever skipped a winter, opting to spend October through April in Australia instead of in the northern hemisphere. Coming back to America the following summer, I felt like something wasn’t quite right. I felt like I had missed that vital internal reset period that feels so intrinsic to my nature.

Now, as summer has officially started and the solstice has passed, darkness will ever so slowly return to the northern hemisphere. This time, I am staying put in the north for the foreseeable future. Darkness, and all it brings, will finally come to me. No longer will I have to stay up so late desperately seeking darkness. I will finally get the strong seasonal reset period that my body and mind have been craving. It may be the height of summer now, but I’m already looking forward to winter.

Night Lights

A photograph is a modicum of truth as it captures an instant in time, a scene reflective of precisely how everything appeared the moment the shutter was released. True? Not exactly. The realm of photography is filled with all sorts of trickery and inexactness. In fact, as early as there has been photography, there have been those using the medium to alter the way reality is captured and presented. Images on film do not appear precisely how even our own eyes view them. This is because of the effect of optics—cameras, as well as our own eyes, are merely just optical sensors. Both take in light photons and use them to gather information about the world. For our eyes, photons fall upon our retinas and are manifested by our brains into our vision. For a camera, the photons fall upon the film (or in digital photography are recorded on a computer) and render what we call a photograph. Under most circumstances, the images generated by a camera are similar to what we’d view in real life. But when the level of light gets low, a whole new world of photography opens up, one where the varying levels of light can create interesting scenes through different levels of exposure.

The following photographs I took at night as a few experiments in capturing the scenes of light and darkness around Camp Burgess.

The night sky is full of the light of stars. It’s beauty causes us to gaze heavenwards with wonder. Though our brain can process the combination of light and darkness just fine to render a starry image, a camera cannot simply point and shoot a scene from the night sky. The level of light is just too low to record anything but blackness. In order to photograph the night sky, the shutter of the camera must remain open longer than an instant. For as long as the camera’s shutter remains open, light falls on the sensors and the image being rendered is evolving. For this photo of the Big Dipper through the trees, I left my camera’s shutter open for 30 seconds. In the dimness of night, leaving the shutter open for that long enabled the stars, as well as the trees in the foreground, to appear in the scene. (If you’re having trouble seeing the images, then turn up your computer’s brightness)

The following four photographs all were shot from the same location.

Here is the night sky again, with the forest in the foreground. The exposure time was set for 30 seconds, which allowed the stars time to emit enough light to be captured in the image. The outline of the Milky Way can be scene across the sky. This is pretty standard night sky photography.

But I decided to use the optical sensing of the camera to my advantage to create some digital trickery. The night sky is great, but I wanted to see how some artificial light would look in the exposure. This is the same image as before, except that I shone my green star laser in front of the camera while it was recording the image. The streaks of green that were only temporary flashes in the sky look as if they were shining beacons from within the cosmos.

Instead of adding artificial light to the sky, for this image, I added extra light to the trees in the foreground. This is a photographic technique known as light painting. The additional light shone on a nearby object is captured during the long camera exposure, causing a highlighting effect on that object. With this, the details of the trees in the foreground can pop out.

For my final photograph of the series, I increased the exposure time from 30 seconds to a few minutes. The increased length that the shutter is open permits an accumulation of light to enter the camera sensor and be recorded in the image. The wonderful thing about exposures at night longer than a few minutes is the ability to capture star trails. Since the Earth is continually rotating, the placement of the stars changes in the course of the night. This change is below our threshold of perception, but not the camera’s. In a star trail photograph, the stars themselves appear to move across the sky, leaving a curved bright streak showcasing where they have been. I absolutely love star trails. Unfortunately, from my location in Sandwich, Massachusetts, the light pollution was too much to capture star trails. After just a few minutes, the light from the nearby city dominated the image. The resulting photograph looks like a foggy forest captured during daytime. But remember—this photograph was taken in the dark!

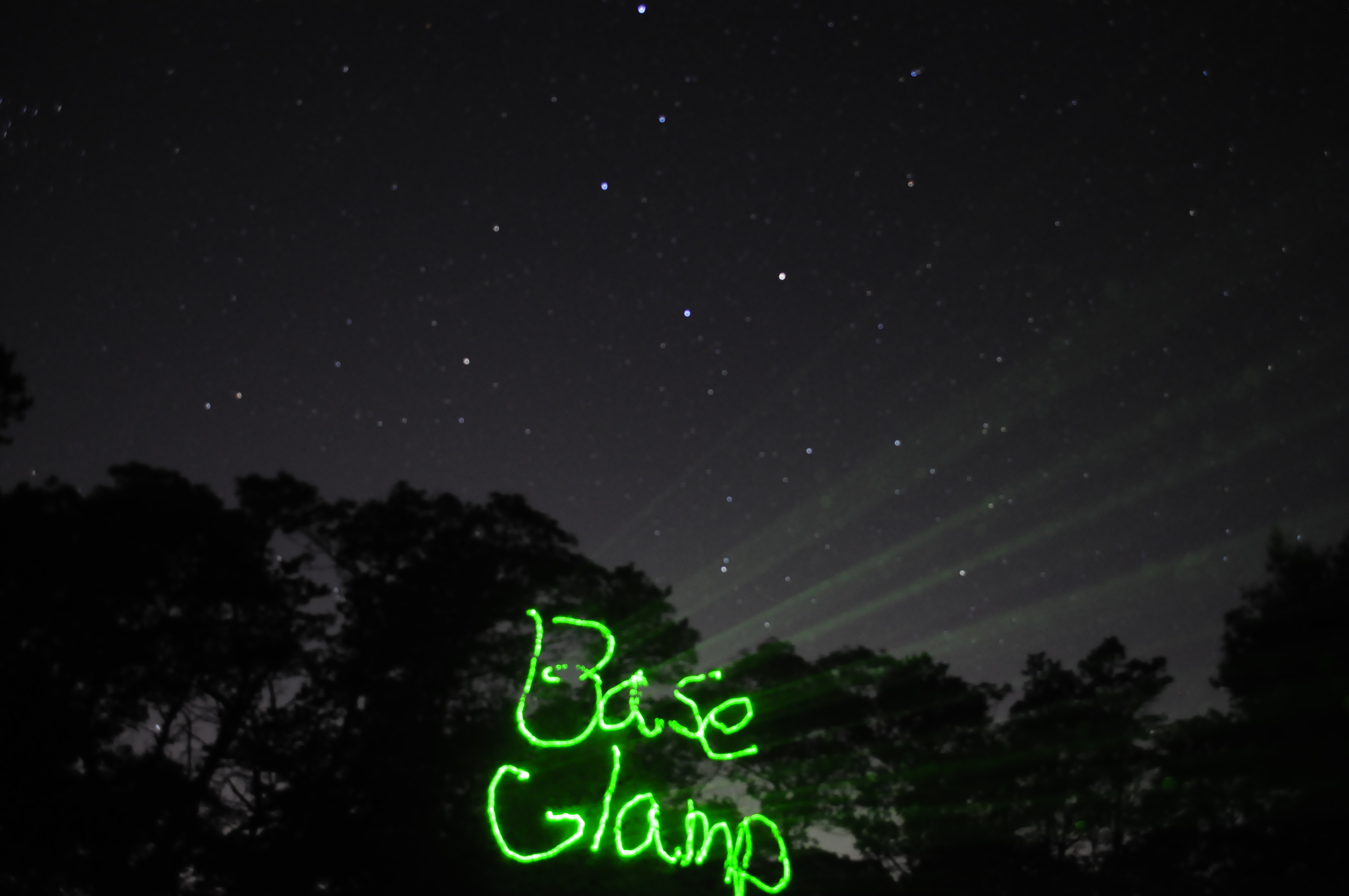

Some more fun with artificial lights here, and some more light painting. Here, I used my high-powered green star laser to write some words on the trees in the foreground. The light emitted from the laser is strong and concentrated enough to appear like a neon tube-light in the trees. “Base Glamp” is the nickname of where I’m working this summer.

More fun with lights in the dark. Similar to star trails, any moving artificial light that falls upon the camera’s sensor gets recorded as a streak in the image. Here I had a few friends walk through a field in the darkness as they shined a few flashlights and headlamps around while the exposure time was set for 30 seconds. The resulting light streaks and spotlighting effects always cause an unexpected result. Though the scene itself is nothing much, the very process of recording the image provides a good artistic flair.

Low levels of ambient lighting at night provides an opportunity to capture scenes highlighted by a single light source. Here, the scene in the composition is dim and the only light source is from a single headlamp. Hence, the hands are illuminated while everything surrounding them fade into darkness of the nighttime.

Fire can also provide a source of light at night. The beauty of flames and glowing embers is pleasing to look at as well as to photograph. Compared to the stars, the light emitted by a fire is bright. It takes an exposure of only a few seconds to capture an image like this.

Finally, using my zoom lens, I can safely get close to the fire to photograph a macro of the glowing coals. Just a few seconds exposure captures the soft, glowing light of the embers but blurs the flames crawling from under the log on in the middle.

Crepuscular Awakening

space

To go in the dark with a light is to know the light.

To know the dark, go dark. Go without sight,

and find that the dark, too, blooms and sings,

and is traveled by dark feet and dark wings.

–Wendell Berry, “To Know the Dark”

space

There is a certain phase between day and night, a time of transition, where the diurnal blends into the nocturnal. These periods of emergent light and shifting darkness make up the twilights of the day—the bimodal intervals between dawn and sunrise, and between sunset and dusk. This is a time on the edges, on the border of binary classification. Organisms that make their way about in these in-between times are known as crepuscular. Those active strictly in the morning twilight are the matutinal; those active solely in the evening twilight are vespertine.

Many familiar creatures make their way about in this altered level of light, taking advantage of both the dimness and the illumination. This is the time to be crepuscular. Under these conditions, a multitude of large forest dwelling creatures emerge—bear, deer, moose—along with their small mammal compatriots: skunks, raccoons, possums, rabbits. Many creatures of the air take flight. The insects—mosquitoes, moths, fireflies. The birds—the owls, the nighthawks. The charismatic bats also take wing. It is now that the active behaviors of these creatures peak. To bear witness to these crepuscular awakenings, the intrepid observer must come join the experience, without light, as a member of the dark.

You are in the middle of it now. Let your feet and voice be silent as you travel in deeper. You will find that the woods are alive with sounds and movements. Careful! Listen close! You too will hear and know the character of the fading light. Though the growing darkness distorts your human vision, fear not. There is nothing to be afraid of in these woods. Nothing in the night is any more dangerous to you than during the day. With transformed senses and unfamiliar sensations, your mind fills in the gaps and imagination runs wild. Yet don’t be alarmed. These crepuscular creatures are more afraid of you than you are of them. Relax. Stay a spell. You may become privy to the hoot of an owl or catch the gliding wisp of a bat overhead.

This twilight journey has been a distinctive experience for you, for humans are not crepuscular creatures. We are largely diurnal, adapted to the brightness of day. Our main sensory experience, our vision, works best in broad daylight. As the day fades into twilight, our eyes begin to cope. The iris expands and the pupils dilate to allow in the dissipating light. Inside the eye, the cones—the sensory cells that detect color and detail—begin to shut down in the dimness. Colors begin to fade, details blur. The acuity of vision diminishes. Yet within the eye, the counterpart of the cones—the rods—begin to become engaged. With the activation of the rods, contrast and shadow become keener, movement more detectable. The silhouettes of trees overhead begin to pop against the dimming sky. The rods readily pick up movement in the periphery of your vision. What was that?!? Did something move? In your periphery, you may detect movement, but oh what tricks your mind may also play on you! The darkness is unfamiliar territory; you are more wary, more attuned to sudden movement.

Yet there are creatures about. There is an abundance of life that is indeed adapted to the crepuscular world. The fading light offers a veil of protection for easy prey, yet illumination enough by which to forage. Predators, too, make use of the twilight as a time of feeding. Equally adapted to the hunt, the crepuscular predators seek out their crepuscular prey. In the twilight, the never-ending battle of evolution ebbs on. Owls, marauders of the night sky, have large eyes adapted to gathering the few rays of light available; binaural hearing, also known as asymmetrical ear placement, allows the owl to detect differences in sound occurrence down to 30 millionths of a second, letting them pinpoint even the tiniest rustle on the forest floor. Overhead the sky is filled with the noise of sound waves, inaudible to the human ear. The bats have emerged and fill the night sky with their echolocation. By emitting their sonar in flight, bats are able to precisely locate the abundance of crepuscular insects upon which they feast. It is a world of eat and be eaten.

All daylight has now faded. At astronomical dusk, the light from the sun no longer can reach over the horizon—it is now as dark as it can get. The period of crepuscular animals is ending. Patiently they will wait again until the next time of twilight. Truly nocturnal animals now make their way about the forest. Take a moment to gaze up now. The sky abounds with a brilliance of stars. Even in the dark, light from a thousand distant suns still caress the planet with their brightness. Even in the darkness, there is light. Even in the darkness there is knowing.