Author Archives: tylerbleeker

Te Araroa Packing List

.

Let me confess that I am not an ultralight backpacker. Or that I even concern myself much with the weight I carry in my pack. When on a camping trip, I like having all the various comforts and amenities along with me, and no matter how heavy my pack is I still find a way to carry it. My tendency to overpack is not helped by owning a 100-liter pack that, no matter the length of the trip, I somehow always find a way to stuff full.

Ultralight backpackers, on the other hand, become obsessed with ounces. Experienced ultralighters can get the base weight of their gear down to 15 pounds or less. They find myriad creative ways to reduce weight, like cutting off the handle of their toothbrush or using a tent-stake as an eating utensil instead of packing a spoon. Yuck! Personally, I don’t mind carrying the extra ounce to have a spoon that is solely reserved for eating.

The bulk of my backpacking experience comes from working as a trail guide at YMCA Camp Menogyn, which, with its emphasis on extended backcountry expeditions for youth, is concerned more with carrying all the necessary gear for an expedition and is less concerned about how much all of it weighs. Menogyn is not an ultralighting outfit in any sense of the word. This past summer, I led the longest backpacking trip that Camp Menogyn offers for its participants, a 40-day excursion to Alaska’s Arctic National Wildlife Refuge (ANWR). My 100-liter pack’s base-weight was somewhere around 40 pounds. Add in shared group gear and provisions for two weeks at a time, and my pack could weigh as much as 70 to 80 pounds—or more! Aside from weigh-ins for our bush plane flight, we weren’t too concerned about how heavy our packs were. All we really knew was that they were heavy!

Backcountry camping Menogyn-style, we needed to carry all that we could envision needing for forty days in the wilderness—repair kit, first-aid kit, extra food rations. Gear breaks and needs to get fixed, the food resupply plane might not arrive on time due to weather, and we needed ample first-aid kit supplies for anything upwards of a grizzly bear attack. Backcountry camping is about carrying enough supplies and knowing how to use them to prepare for every eventuality. But of course, it’s not just all about the necessities either. My group carried, for our entertainment, the luxury of a frisbee and plenty of books as well. And no, none of us ripped apart and burned the pages of our books as we read them—not even David Foster Wallace’s 1,079-page tome Infinite Jest. My reading on this trip included a book about two authors/filmmakers who spent five months in the Canadian and Alaskan Arctic following caribou—though their packs weighed upwards of 100 pounds with camera gear and provisions, they still found the wherewithal to pack a George W. Bush doll so that President Bush could too see the Arctic (cue the video in the link to 3:45 to see the Bush doll’s cameo).

As I transition from an extended backcountry expedition in Alaska to a thru-hike of New Zealand’s Te Araroa trail, I’ll be encountering a very different style of backpacking than I’m used to and have been trained on. So different in fact, that I might as well be starting from scratch! Aside from a lot of the gear looking similar, not much of the practice of travel is the same.

Backcountry camping, like I am accustomed to, is about spending a significant portion of time in federally-designated wildernesses, or areas with little human influence. Thru-hikes, which include more famous trails such as the Appalachian Trail and the Pacific Crest Trail as well as Te Araroa, also pass through many wildlands—but include lots of contact with the developed world as well; in the case of Te Araroa, the trail passes directly through New Zealand’s two largest cities, cuts through miles of sheep pasture (it is New Zealand, after all), and is around 15 percent hiking on roadways.

Another large difference is that backcountry camping does not necessitate hiking a large number of miles each day. In ANWR, our group averaged just four miles of ‘progress’ each day towards our end point of the Dalton Highway. This relaxed schedule allowed us to be free to set out on day-hikes and wander more or less where our hearts desired within the Refuge. In fact, Arctic National Wildlife Refuge has no designated hiking trails. On Te Araroa, the objective will be to get from Point A—Cape Reinga, the northernmost tip of New Zealand’s North Island—to Point B—the city of Bluff, the southernmost tip of the South Island. I will be following closely the trail of Te Araroa the whole time—hopefully not head-down looking at my feet constantly, but looking about and enjoying the scenery. But ultimately follow the trail I will, and the daily goal will be to put on the miles to complete the trail in an ever-shrinking time window (my hiking partner Annemarie has a firm deadline to return to work at McMurdo Station, Antarctica, and I last-minute delayed my start on the trail by about two weeks when an opportunity popped up the night before my departure). With 2,000 miles to cover, and potentially only 3 ½ months to do it in, we could be faced with hiking an average of 19 miles a day. Woof!

Finally, the difference in the food. In ANWR, my trailmates and I carried so much food on our backs—up to 15-days’ worth—because we could only get resupplied only so often by bush plane. In order to carry that many meals, our food needed to be dehydrated, and all 40 days’ worth of food was packed well ahead of the trip itself. Given the amount of time that our dehydrated trail food spent sitting in thin plastic bags all squished together, it is no surprise that all our provisions tended to meld into the same generic trail-food taste. With thru-hiking, I do look at food as being an upside. While the South Island of New Zealand does have several long sections between towns, the number of miles we will cover each day will allow for more frequent resupplies of our provisions. And also the chance to eat at restaurants and fast food! Indeed, my perception of thru-hiker victuals is hiking all day long just to eat at the next McDonalds.

With all this in mind, here’s what I currently have planned to take on Te Araroa. I did myself a favor by downsizing to a 65-liter pack so that I can’t stuff it too full. Currently I have my base weight down to just under 30 pounds. How much of this stuff I will still be carrying at the end of the trail will be a guessing-game over the next 2,000 miles. I included brand names and trade names just to be specific about the gear I have, but recommend finding whatever works best for you, whether brand name or not. I myself have little brand loyalty and have amassed my outdoor gear collection via Craigslist, the REI® Garage Sale™, and discount sections at outdoor gear stores.

.

.

Backpacking and Sleeping Gear

- Osprey® Rook™ 65-Liter Backpack

- Mountainsmith® trekking poles

- REI® Zephyr™ 25⁰ synthetic sleeping bag

- Sea to Summit® Thermolite™ sleeping bag liner (+10⁰)

- Nemo® Tensor™ inflatable sleeping pad

- The North Face® Asylum Bivy™ single person tent

Clothes

- Hiking Clothes

- 1 sunhat1 pair sunglasses1 synthetic shirt1 Original Bug Shirt Company® bug shirt1 pair synthetic underwear1 pair trail running shorts1 pair synthetic socks1 pair La Sportiva® Bushide™ trail running shoes1 cotton handkerchief1 rain jacket

- 1 pair rainpants

- Non-hiking clothes

- 1 synthetic shirt1 lightweight fleece1 medium weight fleece1 puffy jacket1 pair synthetic underwear1 pair synthetic convertible pants/shorts1 cotton handkerchief1 pair lightweight gloves1 beanie1 pair Xero® sandals1 pack-towel

- 1 pair synthetic socks

.

.

Cook-Kit

- Optimus® Crux™ stove with case (uses isobutane/propane fuel available in New Zealand)

- 1 2-liter aluminum cookpot

- 1 potgrips

- 1 spoon

- 1 rubber spatula

- 1 Leatherman® multi-tool

- 1 plastic tupperware

- 1 lighter

- 1 small bottle Dr. Bronner’s® biodegradable soap

- 1 small green Scotch-Brite™ pad

- 1 bottle Potable Aqua® iodine tablets (50-count)

- 1 stuff-sack for carrying food

- 2 32-oz Nalgene® water bottles

Toiletries

- Small tube of toothpaste

- 1 travel toothbrush

- Small tube of sunscreen

- Small tube of hand lotion

- Small bottle of hand sanitizer

- 1 small first-aid kit in an old pill bottle

- Moleskin®Assorted small bandages1 roll athletic tapeAnti-biotic ointmentDiotame anti-diarrheal tabletsIbuprofenHydrocortisone creamSmall and large nail clippers

- Tweezers

Electronics

- Petzl® Actik™ headlamp with rechargeable battery

- Luci® Base™ solar charging lantern

- New Zealand wall outlet adapter

- American charging block

- Charging cord compatible for all electronics

- Smartphone (to use for photos, staying in contact, and navigation apps for the Te Araroa)

- Wristwatch

Extras

- 1 Repair Kit (fitting inside old pill bottle)

- Gear repair tapeInflatable sleeping pad patchesThin sewing threadThick waxed sewing threadAssorted sewing needlesSafety pinsZip tiesDuct tape wrapped around pill bottle

- 2 spare shoelaces

- Journal

- Pen

- Book (Jennifer Pharr Davis’s The Pursuit of Endurance. Why not start off with a book on running the Appalachian Trail?)

- Aluminum wallet with ID, New Zealand cash, and credit cards

.

Happy Trails!

.

.

Chasing Light

It seems I’ve been chasing light lately. First an Austral Summer below the Antarctic Circle. Then a Boreal summer above the Arctic circle. In a few day’s time, shortly after the autumnal equinox has ushered in fall to the northern hemisphere, I will board a plane and fly back to the southern hemisphere for the start of spring. I seem to have become a season hopper.

With three summers in a row without a winter season in between, you’d be forgiven if you thought I was chasing warmth and sunshine instead of chasing daylight. Though astronomically speaking, the seasons have been summer, traditional ‘summer’ weather has been neither what I was seeking or have experienced. Last December I spent the solstice in Antarctica, though even the peak of summer there felt climactically akin to my brethren at home in the Midwest. This June, I was in northern Alaska for the solstice. Yes, temperatures could rise and be unbearable under the full, circling, blazing sun—but it could also become cloudy and reach temperatures within the range of snowfall. Indeed, though the daylight has indicated summertime, these summer seasons haven’t always seemed particularly ‘summery.’

And here I go again, back to New Zealand, back to the southern hemisphere, and back into another summer season. It wasn’t by design that this happened—circumstances and the development of life decisions just produced this unintended result. While working in Antarctica last October through February, I met someone who convinced me to join her on a thru-hike on New Zealand’s Te Araroa trail. So, while the days are short and the snow falls in the northern hemisphere, I will be on the other side of the globe chasing the warmth and summer season as we hike the island together. As we follow the trail from north to south, we will be reaching higher and higher latitudes where in summer the days become longer and the nights are short.

In the temperate mid-latitudes where New Zealand lies, the distinction between periods of night and day are pronounced, but not extreme. But life, as well as the landscape, reaches towards the extreme the more one goes poleward. And beyond the Arctic and Antarctic circles, the land goes from 24-hour sunlight in the summer to 24-hour darkness in the winter. The polar regions are places of extreme seasonal differences. The summer season knows not the winter season, and the transition between the two is abrupt with only truncated springs and falls. From the sun circling overhead continually in the summer, there is only a short transition until the suns sets and never peaks above the horizon in winter.

I have seen firsthand the way the sun wanders aimlessly around the polar summer sky, circumambulating. At McMurdo Station, Antarctica, 77.5 degrees south, I spent 118 days without a sunset. When it finally did occur, the first sunset of the fall was a momentous occasion. The residents of McMurdo piled outside to watch as their faithful sun companion dipped briefly below the horizon, only to rise less than an hour later. And though the sun had officially set, it was far from night, and would be for quite some time. In the beginning of fall, the sun stays so close to the horizon that it remains civil twilight for hours after sunset. Not until a month and a half after the first sunset of the fall does McMurdo experience its first true minutes of night.

With traditional distinctions between day and night becoming muddled at the poles, day and night become somewhat irrelevant. How is one to tell the passage of time when one cannot tell when one day slips into the next? In summer, the sky remains constantly lit. Day rolled into night, but the night seemed just like the day.

In Antarctica, during the summer season, I ended up working the night shift at McMurdo Station. Though the 24-hour clock that the research station ran on considered the shift to be ‘nighttime’, there was no darkness. The only indicator of night was that the throngs of researchers and science support staff hanging out in the galley would slowly subside; there would be a few hours of peaceful quiet while the station slept, until folks began to roll into the galley for coffee and breakfast at the start of another workday. Meanwhile, in those quiet hours in the wee of the morning, the sun was at its lowest angle on the horizon, sending in radiant beams of light through the bank of galley windows—a middle of the night golden hour.

I had no problem adjusting to working the night shift after spending my first few weeks on station as a daytime worker—the sun was as bright as always, and I did not feel like I was sleeping away and wasting daylight as I had felt when I worked overnights for big-box retail. Inside my windowless McMurdo dorm room, the lights were always off. When I needed nighttime, I could retreat to my room and sleep soundly out of the sun. But were I to choose to go out and play instead, the sunlight would be my constant companion.

I had more experience living under the midnight sun this summer, as I led a 50-day backpacking trip north of the Arctic Circle to Alaska’s Arctic National Wildlife Refuge. Our latitude was not quite as high as McMurdo—only at 69 degrees latitude—thus the extremes of sunlight were not as pronounced. But what this trip to Alaska lacked in sheer latitude, it made up for in intensity of experience. Gone were the modern conveniences of McMurdo Station. There was no longer any indoors to hide in, no eternally dark dorm room or dimly-lit dark bar to retreat to. Instead, we were out in the backcountry with no more than we could carry upon our backs. Our only shelter was a thin-walled tent, and the daylight filtered right in. We either made friends with our eyemasks, or we learned to sleep in the light. Once again, the time of day became irrelevant—there was no hiding from the constant presence of the sun.

It took a number of days before I lost the nagging feeling that comes after looking at the late hour on my watch and feeling the pressure to get a hustle on to make camp before darkness falls. Throughout the duration of the trip, I kept tabs of the time on my watch—not out of necessity, but more out of a curiosity of how our circadian rhythms were adapting. Our days slowly dragged out to be longer, as we stayed up later enjoying each other’s company and slept in longer the following mornings. Thus, we ended up being awake through the darkest hours of the day, and even towards the end of the trip after the sun had been setting below the horizon, the light remained with us. Even in the depth of night on our last day in the Wildlife Refuge, it remained light enough in the tent to read a book.

In spite of the mounting fatigue from daylight that comes with constant exposure to lightness, I appreciated the daylight as a benign and amiable companion in a remote and unfamiliar terrain. Here we were, traveling for weeks in the Arctic National Wildlife Refuge, where wolves and grizzly bears roam wild. The signs of these animals were all over—tracks, scat, kill-sites. But the daylight made the wilderness seem friendlier. All told, we saw six wolves and seven grizzly bears on the trip. Seeing the bears and watching their natural disinterested movements in the daylight provided much more psychological comfort for us than wondering if out in the darkness somewhere was a bear lurking just outside the tent.

At about the same time on the trip that I began to miss the creature comforts of home—dry feet and doorways instead of tent zippers—I also began to miss the darkness. Aside from being able to sleep better in the darkness, I began to miss darkness not for darkness itself, but for what it brings to us. The constant daylight drowns out the stars all polar summer long. I’m constantly reminded that people forget this, as I am asked quite often if I saw great stars or aurora. Unfortunately, I was able to see neither stars nor aurora, much to the disappointment of my star-gazing self. And too, having the darkness creep in at the end of the day provides a natural daily cycle of gathering in your shelter for rest. Darkness too, lends itself to gathering around a campfire for light and warmth. Though we did have a campfire on the riverbank one night in Alaska, the magic of the fire just wasn’t the same in the light hours.

As much as I began to miss the darkness, when it finally did come, it felt uncomfortable and foreign. Towards the end of our trip, the nights had been gradually growing dimmer. But right after leaving the Wildlife Refuge, we caught a shuttle ride to Fairbanks, which sits below the Arctic Circle. Darkness descended upon us as we camped in Fairbanks that night. For the first time in nearly two months, it was no longer light enough outside to walk around without a headlamp. The feeling was unfamiliar. Suddenly all the scary feelings of darkness came rushing back in that gut-wrenching primordial fear of the unknown. My how easy it is to forget what darkness is like!

This coming summer, the distinction between day and night will not be as pronounced as I hike the Te Araroa as it was when I spent time closer to the poles. The mid-latitudes will provide a kinder balance of light and darkness each day. Nevertheless, as fall and winter begin to descend on the northern hemisphere, I will once again be off chasing light.

State of Mind, State of Being

space

The United States of America, with its fifty nifty geographical sub-units, neatly divides up this diverse nation into different states that each has a generalized culture and personality. As someone who is not yet settled down with a permanent address, I still have the flexibility and open-endedness to decide which state I want to live in for the long haul. From working jobs in a variety of locations, I have gotten a taste of many different geographies, a smörgåsbord of potential places to call home. In any given year, I seem to work in about three different states, which doesn’t usually include my birth state of Michigan. This prolonged period of ‘geographical investigation’ has given me some insights into where I might want to settle permanently based on my experiences in each state. While I have explored around the country quite a bit (see this page on my personal website for the most up-to-date map of U.S. counties I’ve been to), I’m a northerner at heart—I’ve never stayed long in a place under 40°N. And while I’ve worked jobs on both the East and West Coasts, I always return home to the Midwest.

From my adventures, I have my own thoughts about potential locations to settle, as well as to what my ‘soul state’ might be. But I thought I’d elicit some help from the omniscient ether—by taking a number of sleazy internet quizzes to see where the quiz writers think I belong. These quizzes—though far from scientific—are quite fun to play around with. I’ve listed them here according to my self-rated quality of the quiz, from best to worst:

What were my results? Out of seven quizzes taken, surprisingly none of them yielded the same state. However, there seems to be a strong connection to northern New England, as I was matched with Maine, New Hampshire, and Vermont (even though New York is not considered part of New England proper, I’ll clump it in with this category because the most desirable part of New York for me, Upstate, has a lot in common with northern New England). These four states—charming small towns, more rural populations, historic places, and winding roads through hills and deciduous forests—all seem to be a good match for what I’d be looking for in a habitat. The quiz from Quizony was the only one that picked what I consider to be my ‘soul state’ of Vermont: fiercely-independent, sustainability-minded, ample greenery, and the fewest Wal-Marts of any state.

space

space

space

space

space

And as for my natal Midwest? Sadly, no quiz matched me with my birth state of Michigan. I guess it turns out that I don’t fit in with the bulk of the state, though I think quite highly of life in the rugged frozen Upper Peninsula (Yoopers are a special breed, and I don’t think I could ever live up to their cred). I was quite happy that Wisconsin appeared as a match. I really am fond of the upper Great Lakes region, especially around Lake Superior, and I’ve been quite frequently perusing for real estate in northern Wisconsin. Cheese curds and a good football team? Count me in.

space

space

Then there were two far-flung results. Washington State, with its forests, mountains, and avid outdoor recreation culture seems to be a good fit for me. And though I enjoy visiting and recreating in the west, the West Coast has never really felt like home to me. Finally, my most out-there match was with Tennessee, provided by Buzzfeed. Apparently the quiz determined that I have an undiscovered penchant for country music that makes me belong in the South (even though when given the quiz question for musical preference, I explicitly chose rock over country).

space

space

space

Of course, no online quiz can ever compare with the process of getting to know a state in person. So get out there and start exploring to find your own perfect state!

space

space

space

Flirting with a Smartphone

spacespacespace

My close friends may know that for a millennial, I am quite a technological holdout. I still use Microsoft Word 2003, listen to music on a 4th-gen iPod Nano, and have yet to use social media platforms like Snapchat or TikTok. But what probably most makes me a Luddite is that I still have not acquiesced to the smartphone.

For the second time in my life though, my reliable brick of an ‘unsmart’ flip-phone is becoming obsolete long before it quits working. Network upgrades to 5G will soon render my 3G flip-phone incompatible.

And recently, I was loaned a smartphone to use while on a temporary job assignment, a phone which I was allowed to keep after the job was finished.

Am I now at a crossroads where I’ll join the darkside and become a smartphone user?

I must admit, having a smartphone has been fun for these first few weeks (although I refer to it as a ‘phone,’ it does not actually have a SIM card and therefore cannot be used to make phone calls, which is the primary definition of something being a ‘phone.’ I have been trying to call it for what it actually is, a ‘pocket computer,’ but the name hasn’t stuck and most people would colloquially recognize it as a phone anyway.)

Whereas in my primitive pre-smart-technological life, I would keep either a mental or written list of things I wanted to look up on the internet, and then wait to boot up my clunky old second-hand computer (c.2015) and do a big internet search session, now with a smartphone I have instant access to the world wide web and instant gratification to search for any bizarre or random thing that pops into my head at a moment’s notice. Having the internet in my pocket makes me realize how often I think of random questions that I’d like to research, and also how often I forget about those curiosities if I don’t immediately look them up.

Adamantly decrying smartphones for so long as I have, I found it funny how quickly I became attached to that little pocket computer companion once it was at my fingertips. Oh how easy it was to check messages and emails, to stay in constant contact with the broader world! I kept a web browser pulled up with my email on the smartphone. On breaks or brief moments of down time I could just so easily check for any new messages. And I constantly did check. Of course this was silly—my life hadn’t changed any—previously, checking my email and other messages every couple of days had been sufficient. And it still was sufficient. But I felt that tug of compulsion to constantly check and be connected just because it was so easy. The FOMO was real and it was strong—I couldn’t stand the possibility of missing something, even if it was just the latest promotional email from a company I bought one thing from years ago.

And then, there was my downtime. That phone was so easily a time filler. Getting off work, I would sit and relax in a big comfy chair, phone by my side. Inevitably I’d start browsing. My favorite site was realator.com. Before I knew it, a couple hours would have passed and I’d have progressed into looking at the real estate market in several far-flung cities that I had no intention of ever living in. Wikipedia rabbit holes were also another vice of mine, one that also got me lost for hours. On those evenings alone, that smartphone proved to be a source of mindless recreation, addictive from all the endorphin hits upon each new stimulus viewed. But it also was a huge time-suck.

After leaving the job that necessitated the smartphone, I lost my access to 24/7 high-speed internet along with the SIM card. My next job had me relocating to Bend, Oregon, and while on the extended cross-country drive, it was tough to give up that instant gratification. No more could I instantly research whatever popped into my mind, say the real estate market in Rockford, Illinois, or learning about what had actually happened at the OK corral. On the drive, I found myself periodically checking the phone like I had grown accustomed to—a habit that was so quick and mindless to form. But without service, the smartphone was little more than a slim computer. I had a lot of time to ponder things on my 2,000 mile drive, but I knew that I could no longer just whip out the phone and look something up. Still, the urge to research things on the phone was strong. Irresistible even. I often found the desire compelling enough that sometimes I just had to curb the anxiety by pulling into a McDonalds parking lot to bum WIFI for a few minutes.

So, after my month-long flirtation with a smartphone, am I ready to make the transition from a flip-phone myself?

Absolutely not. I appreciate my flip phone for what it is, and for what it is not. It is just a phone. It is a utilitarian tool, used to call people. The smartphone, though sleek and beautiful and convenient and powerful, is too much for me to handle. I realize I cannot control myself when with a smartphone. I do not want to be counted among the masses who mindlessly check their phone out of habit at every microcosm of an empty microsecond. I like to be free to be alone with my own thoughts. I do not wish to feel so connected and dependent on a technological device that I cannot bear to have it not by my side.

Some folks make the argument that technology is not the culprit, but rather phone abuse is from a lack of self-control. Phooey. This technology is made to be addicting. Even with my staunch anti-smartphone values and austere self-discipline, I still found myself getting sucked into the mire of addiction. Best to just cut it off and not have the temptation.

In the end, though I have decided to keep the smartphone, I have decided not to get a service plan for it. I will use it only like I use a computer—occasionally and with an intended purpose. And though it is becoming more difficult, I can still operate in a world that is becoming increasingly interconnected and dependent on smart technology. More than anything else, I value the freedom of not being connected all the time. Though the perks of a smartphone are charming, it is not worth the cost to me.

Space

Space

Space

What I Learned from 23andMe

It all started innocently enough the last time I was with my sister. We were talking about how different we are, and I invoked the old teasing trope that my sister Allison was switched at birth (though there is anecdotal evidence, nothing has been scientifically proven at this point). As we were talking, it clicked in my mind that maybe we should take a DNA test to solve the matter. In recent years, at-home ancestry DNA test kits, like 23andMe and Ancestry.com have become quite popular and affordable. I proposed to Allison that we could find out definitively once and for all if indeed we were siblings or not; I would take a test if she would take a test. I have since gotten my test results back, but as of this writing, Allison still has not yet even sent her test in. I’m taking this as a sign that Allison knows the truth and is still trying to hide it…

Aside from settling the matter as to whether my sister and I are actually blood-related, I was mostly curious where the bulk of my DNA comes from. Growing up in America, especially in white populations, we often like to talk about where our ancestors migrated from, whether we definitively know where or not. White people will list off a smattering of European nations, proud of their heritage as a European mutt in this country we refer to as the American Melting Pot. I grew up, however, in a fairly homogenous town, the aptly named Holland, Michigan area where most everyone is to some extent Dutch. It’s no surprise, then, that I considered myself Dutch, and not much else. If you ain’t Dutch, you ain’t much! But aside from growing up in a town with windmills, wooden shoes, and an annual Tulip Festival, there wasn’t a lot of evidence to say how Dutch I actually was—or if I had any other surprises in my genes. Sure, I had a pair of Great-Grandparents who emigrated from the Netherlands, but other than that, my not-so-distant relatives were American-born. My family has a few historical records that show when a small number of distant ancestors migrated, but other than that, it was just generally assumed that my forebears came from the Netherlands. Or northern Germany, as they are geographical neighbors. But the Germans never really got more than a passing mention in my family’s lore.

Upon recommendation from a friend, I decided to go for the 23andMe test kit. The test kit breaks down recent ancestry into a multitude of regions and sub-regions, as well as giving genetic information on phenotypic traits and health risks with a provided scientific backing behind it all. Once I received the at-home test kit, I spit a copious amount into a tube and then mailed the sample away to a lab to await my results. I mostly wanted the results to show how ‘Dutch’ I actually am. Or, if in fact my DNA would have a surprising trace of genes from another ethnicity. Some Euro-American individuals, in an effort to bolster their feeling of diversity, may talk about how one of their distant ancestors was a Native American or an enslaved African-American. There was no such talk of this in my family though. Would the DNA test reveal otherwise?

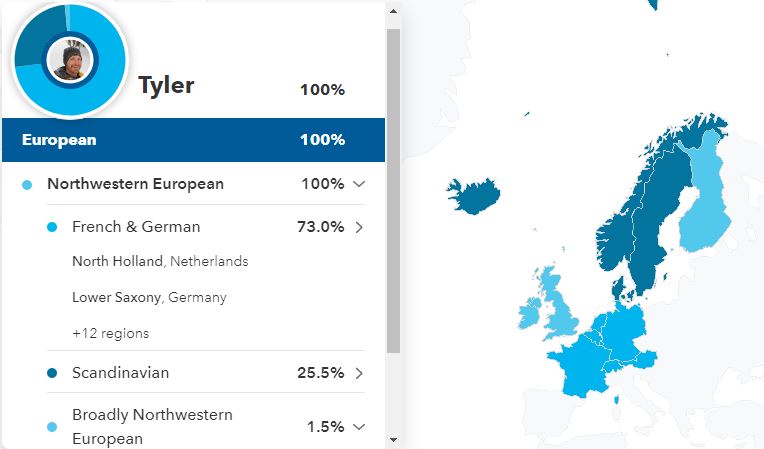

After getting my results back, it turns out I am indeed very white—or more appropriately, of European genetic origin. 100%, in fact. All of my genes come from European heritage (it should be noted that 23andMe types DNA according to particular genetic sequences which are held in common by a reference population with known ancestry to a particular region. These results mean that I share particular DNA segments with people of a known regional European ancestry).

space

space

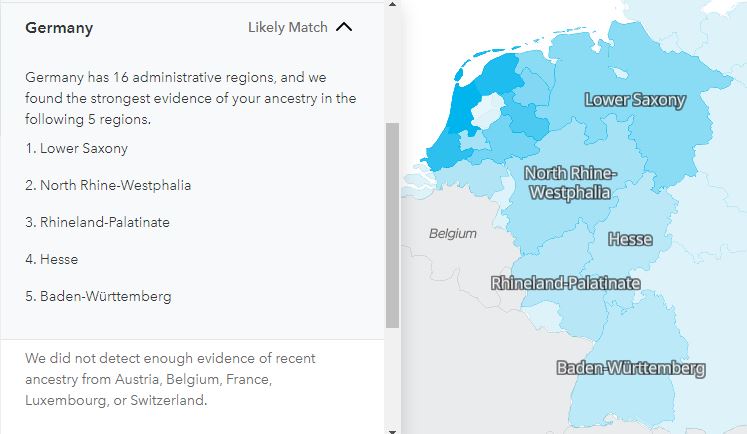

Not surprisingly, as the story told by my living ancestors attests, the bulk of my DNA originates from the Netherlands. 73% match in fact for the category 23andMe titles ‘French and German.’ Within this grouping of countries, 23andMe does not break down ancestry by percentages; instead, ancestry DNA matching is listed by likelihood of a DNA match. Turns out, I’m a ‘highly likely’ match for the Netherlands. This is followed by a ‘likely’ match for Germany. All other countries in the region—Austria, Belgium, France, Luxembourg, and Switzerland—I did not have any likely DNA matches from. Looking at my results, I am mostly Dutch ancestry, as I believed, with the smattering of Germans that my family only slightly acknowledges.

space

space

The biggest scandal of the DNA test, the big surprise that I had been waiting for, was that I am 25.5% Scandinavian ancestry. No one in my family had ever mentioned anything about Scandinavian ancestors! To think that my family has been hiding the fact that somewhere far back in the family tree are a few crazy Swedes or Norwegians! (Given this new information, it now all becomes clear why I fit in so well with the primarily Scandinavian ethnic population of northern Minnesota. Uff-da!)

space

space

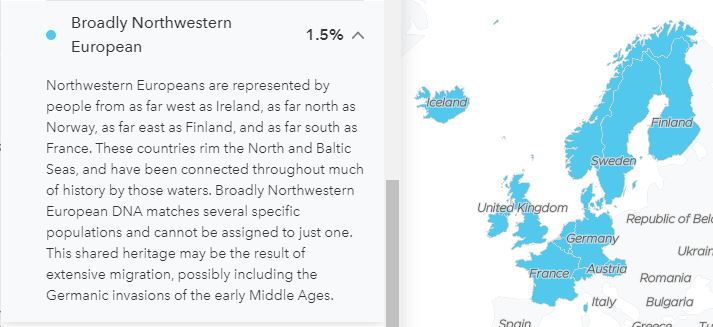

To round things out, the last remaining 1.5% of my DNA is defined as Broadly Northwestern European. These are genes that are common in Northwestern Europe, but not specific to a particular country. To sum it up, I suppose, I am of broadly Northwestern European ancestry. No big surprises in my genes, I’m afraid.

space

space

Reflecting on what I learned, I can’t say that my life was changed too much by finding out my DNA ancestry. It pretty much confirmed what I had already known, or had at least suspected. Before any person takes the test, though, 23andMe does go through a fair number of disclaimers aimed at educating participants in how learning the results of one’s DNA makeup can be upsetting. I am not upset, though. If anything, getting my results makes me even more likely to pursue a long bicycle tour of Northwestern Europe. But I was planning on dong that someday anyway.

Aside from just learning the background of your ancestral DNA, 23andMe offers an outlook into certain genetic traits and health markers. Many of these of course are for disease risk and are quite serious to look at. But there is also the much lighter side of genetic traits, which range from the standard to the inconceivable.

Some of these traits seem intuitive that there is a strong genetic component. For example, 23andMe correctly predicted most of my phenotypic features—blue eyes, unattached earlobes, little to no back hair, an uncleft chin, and no dimples. In regards to hair loss, much to my relief, I have an 82% chance of not going bald before age 40 and an 87% chance of not having a bald spot.

And then the genetic results get more bizarre and interesting, as the trait report begins to list not just physical traits, but also behavioral traits and preferences. These more far-flung personal attributes do have certain genetic markers in common among populations with said trait, as per 23andMe’s research, though the company also acknowledges other physical and cultural factors are at play too. For example, I have about average odds of hating chewing sounds and I am about as likely to get bitten by mosquitoes as others. But, fortunately I’m less likely to be afraid of heights, and also less likely to be afraid of public speaking (I can attest to both). Apparently, according to 23andMe, my circadian rhythm should wake me up naturally at 8:16 AM. I also have less than two percent Neanderthal DNA.

Aside from that, 23andMe says that I’m more likely to detect a distinct odor in my urine after eating asparagus (that’s true…), but also that I’m more likely to think cilantro tastes like soap (I don’t). And apparently I don’t have a particular preference for either chocolate or vanilla ice cream. I’ll actually eat any ice cream. And on that note, I’ll say thank you to my Northern European ancestry which has blessed me with an incredibly high dairy tolerance.

space

space

space

Northern Lights, Bettles, Alaska

Over the winter of 2020-2021, I worked at a remote lodge 35 miles north of the Arctic Circle, in the small, isolated community of Bettles, Alaska. Located in the normally dry and clear interior of Alaska, Bettles is ideally situated under the typical arc of the Northern Lights, or, the Aurora Borealis. On any mostly clear to clear night, from late-August to early-April (when the skies get dark enough to see aurora), the vigilant observer will be treated to some degree of a show.

Though scientists who study the aurora can make forecasts and predictions about when and where auroral activity will occur, much remains unpredictable and mysterious for the aurora chaser. Each night puts on a different show. On some nights, thin distinct bands of aurora will linger in the sky for hours; on other nights, bursts of intense waves, greens and purples, will wriggle and twist their way across the sky in just a matter of minutes. Clouds or a full moon make the aurora appear vastly different than on a clear moonless night. Whatever the conditions, when the aurora do appear overhead, the viewer is guaranteed an excellent show unlike any other.

The following images and time-lapse videos I captured in and around Bettles, in the winter of 2020-2021.

An auroral forecast, along with an FAQ section about the science of the aurora, can be found at the University of Alaska Fairbanks Geophysical Institute website.

Space

Space

Space

Space

Space

Space

Can a Collector Live in a Tiny House?

space

I found a rock the other day. A shiny metallic piece of schist about the size of a travel bar of soap. It’s a beautiful specimen of its own accord, found as part of the mélange of rocks jumbled up in Alaska’s glacially-formed landscape. I decided to keep the rock as a small souvenir, a tactile memento of my first winter spent in interior Alaska. Amateur geologist that I am, I thought the schist would make an excellent addition to my rock and mineral collection.

You see, I am a collector. My rock collection is testament to this. Boxes and boxes of rocks I have picked up from places I have visited now sit begrudgingly in my parents’ basement. The finest specimens I keep on display in a little nook in their basement workroom, but without a permanent space yet to call my own, most of my treasures still wait in expectation for when they will once again see the light of day.

The rocks I collect are not only intrinsically beautiful, but they all have added meaning for where I was when I collected them. I am a collector—of things, yes, but also of experiences. Working as a dog musher north of the Arctic Circle is just the latest life experience I am collecting. Though I won’t need to hold the little piece of schist in my hand to remember my winter spent in Bettles, Alaska, it can serve as a conversation starter or as a token to trigger my memories of time spent here.

At the same time that I am adding to my ever-expanding rock collection, I am also living in a repurposed trailer that housed construction workers who built the trans-Alaskan pipeline. Some nights I theoretically sketch out in my head if I could imagine an entire home being placed in the 8’ by 14’ unit that makes up my apartment. Kitchen here, bathroom there, sleeping loft above. It’s an enthralling exercise, as I have a growing interest in tiny homes. Living in staff housing, as I typically do, I am accustomed to occupying smaller spaces, though none of them ever being a bona fide tiny home and none ever being a permanent residence either. Regardless, constantly moving into and out of staff housing for the past number of years has given me great practice in small living, as well as showing me how simple it can be to live out of a couple duffel bags in a small space for an extended period of time.

But sometimes I have to wonder to myself: can a collector of things live in a tiny house?

space

space

It seems like my desire for tiny house living might be at odds with my natural inclination as a collector. The tiny house philosophy, after all, is about living a life with fewer things in general. To live in a small space, you have to cut out what is non-essential. I’m afraid it may be that my rock collection, though exceedingly cherished, is fairly non-essential to my everyday life.

And yet though I contemplate tiny house living more and more, the older I get the more things I accumulate, and the more reluctant I am to dispose of the things which I have acquired. Though I believe myself to be in one of the lowest percentiles for possessions owned by a 30 year-old American, my various hobbies have resulted in quite a collection of things. In addition to my rock collection, I now own a wide assortment of backpacking and camping gear, snowshoes, cross-country skis, a canoe, and two bicycles. And that’s not to mention other things like the massive volumes of books that I have accumulated. If push came to shove, I believe, I could still fairly readily pack all my essentials into my hatchback with my canoe and bicycles strapped on the outside. As for now though, with ample storage space at my parents’ place, I don’t yet have to make the decision between being a collector and living in a tiny house.

But if I do at some point opt to try the tiny house lifestyle, it might come to the point where I must make the choice between having more things and living simply in a tiny home. As that potential day is still far down the road, I can only speculate what the outcome might be. Perhaps in ten years, my collection of rocks won’t seem as important to me as it does today. Perhaps I’ll somehow incorporate my rock collection into the build of my tiny house. Maybe I will still be a limited collector of things. Or maybe I’ll have to switch to just being a collector of life experiences instead.

Only time and future experience will tell if being a collector of things can be compatible with living in a tiny house. In the meantime, I’ll continue practicing the tiny house ethic of being mindfully intentional with the items I do decide to keep. Each item I decide to hold onto must serve some practical purpose or be imbued with some sort of special significance. With that in mind, I will be very intentional about the one souvenir rock I will ultimately bring home to my collection from Alaska.

Glamour Snoots: Koyukuk Kennel

space

Welcome to the Koyukuk Kennel, the dogsledding division of Bettles Lodge! Meet the team of 17 adorable Alaskan Huskies who are working with me this winter giving dogsled tours in the Alaskan bush 35 miles north of the Arctic Circle. They were all ready for their snoot close-ups with the help of my fish-eye camera lens!

space

space

space

And of course, an equal part of the kennel is our 8 new husky puppies born in early September 2020. Our pandemic-inspired litter of Corona, Curve, Demic, Fauci, Lysol, Kluster, Swab, and Zink!pace

space

space

space

space

space

The Socially Distanced Cyclist: 16 Days, 1,170 Miles, and Minimal Human Contact Around the Coast of Lower Peninsula Michigan

From August 9 to 24, 2020, I took a solo, self-supported bicycle trip to explore the coastline of my home state, the great state of Michigan. Being the Great Lakes State and a water wonderland, Michigan offers 3,224 miles of freshwater coastline to explore as well as 124 lighthouses, both of which are the most of any state. The following is a summary the trip, encompassing 16 days, 1,170 miles, and following the coastline of Lake Michigan and Lake Huron around Michigan’s Lower Peninsula.

Approximate Route:

Day 1: Familiar Territory

Zeeland to Muskegon State Park: 67 Miles

It was a beautiful summer Sunday afternoon when I finally departed for my trip after a much longer than anticipated morning of final preparations. Bluebird skies and temps in the 80’s made it a day more fitting for a beach holiday than a long, sweaty bike ride. I would start the trip covering very familiar territory, a survey of the Lake Michigan beaches within just a short driving distance of where I grew up. I hopped on my overloaded bicycle and listened to the new squeaks and groans as the immense weight found its equilibrium on my old Cannondale, crossing my fingers that no spokes would snap (wanting to keep myself socially-distanced as possible, I chose to pack around 35 pounds of food so I wouldn’t need to re-provision the entire trip). My first leg would be the twelve mile distance to the white sand beaches of Holland State Park, with a ceremonial stop to see my beloved ‘Big Red’ Lighthouse, which would mark the first of many lighthouses I would stop to see on the trip.

The Holland area boasts many wonderful non-motorized recreational paths, and I followed one of them along Lakeshore Drive, past many lakeshore mansions, nearly all the way to Grand Haven. Grand Haven State Park, another beautiful white sandy beach, was packed with beach revelers on such a gorgeous day. From Grand Haven, I crossed the drawbridge over the Grand River and proceeded northward to Muskegon. This first day of the trip was marked by getting through some of the bigger metropolitan areas on the lakeshore to the less developed lands of the northern counties. North of Muskegon lies Muskegon State Park, a much quieter and forested lakeshore dune park than both of the state parks I had visited earlier. It was at Muskegon State Park where I would first camp for the night, and, as an omen for a good trip to come, I found a $20 bill on the road leading to the park.

Day 2: Storm’s A-Brewing

Muskegon State Park to Ludington: 72 Miles

Day two started fairly leisurely on the sandy beaches of Muskegon State Park, followed by a stimulating up-and down ride through the tree-covered dunes to the Blockhouse, the highest point in the park which offers great views of the dune ecosystem. Continuing northward, I followed the aptly-named Scenic Drive paralleling the lakeshore until I reached White Lake and the twin villages of Whitehall and Montague. As recommended, I found the Hart-Montague Trail, which was Michigan’s first Linear State Park and one of the earliest instances of Rail-to-Trail conversions in Michigan (1991). The Hart-Montague Trail runs for 22 miles and connects several small country towns that offer ice creameries and small cafes. Being a former railway, the trail is undeniably flat and straight, with mostly shrubs and brush for scenery. A few miles shy of Hart, I got the itch to return to the lakeshore for more expansive scenery and some hills for interest. I turned west towards the lake and the sand-buggy enclave of Silver Lake. Though I yearned to make the short detour to the remarkable Little Sable Point Lighthouse in Silver Lake, dark ominous clouds had begun building to the west.

I followed roads along the lakeshore through the city of Pentwater and past the cottages of Bass Lake. A few miles south of Ludington, the road passes right by the Ludington Pumped Storage Plant, once the largest pumped storage plant in the world! During the night, when there is excess electricity generated, the plant will pump water from Lake Michigan up into a 1.3 square mile reservoir over 350 feet above the lake. Releasing this water during the day generates supplemental electricity during peak demand. I stopped to gawk at its massive industrial workings, until a security guard came and asked me to leave. The guard said they were shutting down the overlook due to impending weather and showed me the radar on her phone. Yikes! I made a mad bike dash down from the high dunes to the city of Ludington, where I fortunately was able to set up camp before the heaviest rains set it. It was an eventful night as lightning flashed and thunder cracked overhead, but this would prove to be the only rain encountered on the whole trip.

Day 3: This is Hilly Amazing!

Ludington to Sleeping Bear Dunes National Lakeshore: 78 Miles

The storms had passed during the night leaving me with wet gear, but a warm sunny day proved to be in order once again. North of Ludington, Hamlin Lake and Nordhouse Dunes (Lower Michigan’s only federally-designated wilderness area) block road access to the lakeshore, so I took an inland route of country roads through the matrix of forest and small farms. Riding into Manistee took me back to the lakeshore, and proved to be stop with plenty of great parks to relax at along the lakefront. A few miles north of Manistee, while riding on Lakeshore Road, I got caught up in paying too much attention to a car behind me as I looked to turn left towards the beach access. My front wheel slipped off the paved roadway immediately bogging down in the soft beach sand and causing a slow-motion flip over the handlebars. Aside from a few superficial scratches on my hands, knees, and bike, I was shaken, but OK.

I continued on, albeit more wary of soft shoulders now, around Portage Lake and the small town of Onekama. Onekama is the southern terminus of Michigan Highway 22 (or M-22), that famed route whose highway sign is emblazoned on merchandise and bumper stickers all over Michigan. Reaching M-22 proved a dramatic change in riding conditions; here, the hills began. Whereas up until now things had been remarkably flat, M-22 began a series of long, winding, gradual 1-to-2 mile climbs up a sand dune, followed by a speedy descent on the other side. I maxed my downhill speed out at 39 MPH, which on a fully-loaded bicycle is simultaneously exhilarating and terrifying. I broke up the hill climbs with stops at the little Victorian town of Arcadia’s city beach, and at the much more bustling tourist town of Frankfort. I then turned my route inland toward the town of Beulah, in search of cherry pie and wine. Riding from Frankfort along the sizable Crystal Lake proved no relief from the hills, and slower travel over the terrain caused me to miss out on the treats found in Beulah. Hungry and exhausted, I made my camp for the night just a few miles to the north in the Sleeping Bear Dunes National Lakeshore.

Day 4: I Bearly Got Anywhere Today

Sleeping Bear Dunes National Lakeshore: 37 Miles

However exhausted I was from the hill climbs the day before, I woke up very excited for the route I would cover today. I would be traveling through the Sleeping Bear Dunes National Lakeshore, perhaps the most scenic stretch of land in the Lower Peninsula (indeed, Sleeping Bear was named ‘The Most Beautiful Place in America’ by ABC’s Good Morning America in 2011). My bike, however, seemed less up for the challenge. As I had feared, all the popping and groaning coming from my crank were signs that my bearings were going bad, and my crank assembly had been growing disconcertingly looser and looser since day two. I would need to make a pit-stop to have that taken care of before I found myself stranded with no pedals to pedal.

I followed the quiet stretch of M-22 into the tourist outpost of Empire, where I met up with the Sleeping Bear Dunes Heritage Trail. This trail winds through the woods through most of the park, providing most excellent riding scenery. The trail also goes over some very steep dune sections and around some very sharp curves which makes for a sendy route to keep riders on their toes. Highly recommended is the Pierce-Stocking Scenic Drive, which winds a course of seven miles over some of the biggest dunes in the park and past some of the best vistas of Lake Michigan on top of the 400-foot tall sand dunes. Unfortunately for me, and maybe fortunately for my bike, the Pierce-Stocking drive was closed in 2020 due to road construction. However, a short distance north is the epic ‘Dune Climb’, a large active dune blowout that guests are encouraged to climb. The vantages from the top are quite spectacular, and offer sweeping vistas of Lake Michigan, the dune systems, and the valleys inland. Sleeping Bear Dunes also offers opportunities for history hounds as well. Just north of the dune climb is Glen Haven, a former fishing company town that the National Park Service now maintains as a historic village. Tucked in pockets around the park are also the barns and farmhouses of homesteaders of yore. In the course of time, most homesteads folded in the region, and the main economic driver switched to tourism.

I finally stopped to have my bike repaired in Glen Arbor, and the mandatory afternoon of downtime was well spent enjoying a swim in the crystal blue waters of Lake Michigan, as well as doing some tourist shopping in Glen Arbor itself. Not a big day distance-wise, but one of the best places just to enjoy some time in the splendid destination.

Day 5: Up and Down on Leelenau

Leland to Traverse City: 84 Miles

Back in 2012, I had taken a short bike vacation with my parents to the Leelenau Peninsula, and this area offers so much for the bicycle tourist on shorter trips as well as longer ones. The bigger towns of Leland, Northport, and Suttons Bay all offer their own vibe and tourist amenities. I started my day by following M-22 into Leland, of which any stop requires a mandatory visit to the historic and artsy Fishtown. A pleasant and lightly-trafficked ride north on M-22 took me to the quiet town of Northport. About an 8 mile ride north of Northport, past many cherry orchards, I reached the very tip of the Leelenau Peninsula which is home to a state park and the impressive Grand Traverse Lighthouse. The lighthouse was open to tours, though the tower was closed due to COVID.

On my way south on M-22 towards Suttons Bay, just past Omena, I crossed over the 45th Parallel (I had actually crossed over it earlier in the day between Leland and Northport), which, being the geography nerd that I am, necessitated a reason to celebrate. The closer I got to Suttons Bay, the more traffic M-22 picked up, and the worse shape the road became. Though riding M-22 next to Grand Traverse Bay was scenic, I was happy to beat the traffic by picking up the TART Trail (Traverse Area Recreation and Transportation Trail) going into Traverse City. Being the ‘Cherry Capital of the World,’ I biked past many cherry and fruit orchards on my way into the city.

Day 6: On a Mission

Old Mission Peninsula to Charlevoix: 78 Miles

The start of the day would take me onto the Old Mission Peninsula, the very long and narrow stretch of land that neatly divides Grand Traverse Bay in two. I peddled up the Peninsula on the west side’s Peninsula Drive, which offers a very quick and flat route to the tip, going past miles of miles of really fancy waterfront properties along the way. At the tip of the Old Mission Peninsula lies the Mission Point Lighthouse and a nice beach with crystal clear waters. The route back to Traverse City, along the main highway M-37, offered quite a contrast to the solitude and ease of Peninsula Drive. M-37 goes through the middle of the Peninsula, meaning the road goes up and down many hills as it winds its way mostly through vineyards. Though the hills were challenging, they did provide some incredible vistas of vineyards and Grand Traverse Bay. Had it not been before 10AM, I would have stopped for a tasting.

Once back into Traverse City, I caught the TART Trail to its eastern terminus in Acme, a few miles away. I was glad to avoid the heavy development and tourist traffic along that stretch of US-31. Once the path ended, I followed the signed bike route through some bucolic country acres until I ended up at US-31 again. During route planning, I had wanted to bike that stretch of US-31 as it passes on a narrow strip of land between Lake Michigan and both Elk Lake and Torch Lakes. In hindsight, this was the only section of my route that I wish I had changed. US-31 along that stretch has only a narrow, crumbling shoulder, and the summer tourist car traffic is constant. Even worse, the route has absolutely no views of any lake along the way. As a plus side, though, the heavy tourist traffic does bring with it an abundance of roadside food, fruit, and sweet stands, and Elk Rapids makes a nice town to stop at. Given that it was an exasperatingly hot and sunny day, I made my fill of stops along the way to replenish my belly and refill my electrolytes with some pasties, pastries, and apple cider.

Day 7: Through the Tunnel of Trees

Charlevoix to Cross Village: 81 Miles

Whereas the previous two days were spent biking around the Grand Traverse Bay, today I would bike around the Little Traverse Bay. First stop of the day was in the harbor town of Charlevoix, outside of which I picked up the Little Traverse Wheelway bike path. With the underlying bedrock of the region being limestone here, I made several lengthy stops along the lakeshore to try my hand at fossil hunting. Being so close to Petoskey, I was really hoping to find a stellar specimen of the city’s namesake and Michigan’s state rock (even though Petoskey stones are indeed a fossil, they are not Michigan’s state fossil). Alas, good specimens of Hexagonaria coral (AKA Petoskey stones) were difficult to find, but it doesn’t take an expert paleontologist to soon pick out many other fossils in the mix; fossilized horn corals, bivalves, brachiopods, and crinoids all make the lakeshore a Devonian paleontologist’s playground. Following the nicely-paved Wheelway around Little Traverse Bay will take you to the towns of Petoskey and Harbor Springs, both of which offer plenty of dining and shopping amenities. Petoskey offers a large historic downtown area built into a hillside, whereas Harbor Springs caters to the yacht club upper-crust.

Past Harbor Springs, following Michigan Highway 119 (M-119) is both the motorist and cyclist eye-candy route known as the ‘Tunnel of Trees’. The Tunnel of Trees is a splendid, curvy, 1 1/2 lane highway that encourages you to slow down and enjoy being immersed in the trees as the highway meanders along a sand dune bluff for nearly 20 miles. Traveling, as I was, on a mostly cloudy evening, I encountered very little auto traffic (I let my eyes wander once again, forgetting entirely my days-earlier episode of crashing my bike). At the northern end of the Tunnel of Trees is the tiny settlement of Cross Village, most notably known for its iconic roadhouse, the Legs Inn. In the 1930’s Polish immigrant Stanley Smolak, along with the help of local Odawa craftsmen, began to build the fantastical building using local stone and driftwood. It is highly recommended as a place to eat, or at least walk in and feast your eyes on the décor. Wait times often exceed one hour. Though a hot meal and a beer sounded nice after such a long day, I was burning daylight and had to get to my campsite near Wilderness State Park.

Day 8: In the Straits, not in dire straits

Wilderness State Park to Mackinac Island: 45 Miles

Wilderness State Park is a fantastic, remote expanse of land on the northwest tip of lower Michigan. It offers wide swathes of pine forest and vast expanses of sand dunes, and is highly recommended to spend a full day there. My time in Wilderness State Park would prove eventful. I had just started biking for the day when I came around a corner and saw two young men frantically waving for me. I caught glimpse of a motorcycle stuck under a truck, which is what they were making a big fuss about. I stopped to help the two guys, both named Tyler, incidentally, to get the motorcycle out from under the truck. By that time, I had already pieced together the narrative that the man with the fresh patches of road rash had lost control of his motorcycle going around the curve, and had slid under the parked truck. Fortunately everyone was OK, and I helped Tyler clean up his road rash a bit. Of the three of us there, only my flip phone had cell service, and I stayed with them until they arranged a tow. Flip phone for the win!

Since I no longer had time to explore the vastness of Wilderness State Park, I picked my way along rough rural roads in Emmet County towards the very tip of the Mitt at Mackinaw City. Along the way, however, I couldn’t resist stopping when I saw a sign for the McGulpin Point Lighthouse (which, by the way, you could actually climb the tower). From the McGulpin Point light tower, I could get a great view of the Mackinac Bridge spanning the Straits of Mackinaw. I was at the tip of the peninsula, but the Mackinac was a bridge I would not cross (at least not on this trip). Nearby the lighthouse is the Headlands International Dark Sky Park, and the region is perfect for stargazing on a clear night.

Now that I was halfway through my ride and at the tip of the Peninsula, my crowning stop would be an afternoon spent on Mackinac Island, Michigan’s iconic and premier island destination. A former British fort and a tourist destination since the mid-1800’s, Mackinac Island was once even briefly a federal National Park (1875-1895). Today, the island is known for its bikes and horse-drawn carriages, its Victorian architecture, its fudge and tourist shops, and for being carless. It is a half-hour ferry ride to the island from Mackinaw City, and to get to the ferry terminal you have to pass through all the shops of downtown Mackinaw City that are hawking fudge and T-shirts. Once you land on Mackinac Island itself, you’ll be in downtown and will walk past all the shops hawking the same fudge and T-shirts as the mainland. But when you’re on the island, it’s special, and I did the touristy thing of buying fudge, popcorn, and postcards. The island is also great for history buffs, given Fort Michilimackinac and other historic buildings to tour, but I was there for the bike riding. A right of passage on the island is to bike the 8 mile loop on M-185 that rings the island. I had biked around the island once before on a family trip when I was in fifth grade, but biking on my own as an adult was so much better. Of course I had to make a stop at some of the iconic geological formations such as Arch Rock and Skull Cave. And there was no better way to cap off the day than by getting ice cream from the shop below the Grand Hotel’s world-record 660′ long front porch.

Day 9: Lonesome Limestone Highway

Mackinaw City to Thompson’s Harbor State Park: 74 Miles

United States Highway 23 offers a dramatic contrast to the commercialism of Mackinaw City. Never before had I been to northeast Lower Michigan. It is an region of small towns separated by large distances all built on the extractive industries. From Mackinaw City to Cheboygan, the North Central State Trail follows an old railroad grade paralleling Highway 23. Though the crushed gravel of the state trail was nice, I found I preferred the feel of pavement and the glimpses of Lake Huron that riding on the road afforded me. Traffic was light and the shoulders were wide, which meant great riding conditions.

The surrounding waters of Lake Huron are extremely treacherous, and have claimed hundreds of ships and lives over the centuries. These shipwrecks are all protected within the Thunder Bay National Marine Sanctuary. Forty miles from the Straits of Mackinac is the Forty Mile Point Lighthouse. Several shipwrecks lie in shallow water just offshore, but the remains of the 1905 wreck of the J.S. Fay lie on the beach near the lighthouse. Snorkeling, SCUBA diving, kayaking, or glass bottomed boat tours are all the best ways to see the wrecks.

From Forty Mile Point, one can get on the paved Huron-Sunrise Trail, which leads to Rogers City. Though Rogers City is small, its status as the only town of 1,000 or more people for 30 miles in either direction means that it has all the amenities a person would need. Rogers City is built on mining—mining the fossil-rich limestone bedrock that dominates the region. The limestone is crushed and used as an ingredient in cement, and Lake Huron provides easy access for shipping to distant markets. Outside the city is a special overlook that peers into the massive strip mine that gives Roger’s City its lifeblood. The Calcite Quarry, at over 1,800 acres, ships out 7 to 10 million tons of limestone each year.

Leaving Rogers City early in the evening, the sun was beginning to shine lower and lower on the horizon, while the blue open skies made the late sunshine feel quite tangible. I took a detour off of US-23 at Thompson’s Harbor State Park to search for the Presque Isle Lighthouses. Without directions or a detailed map, I followed an unnamed dirt road hoping it would take me to the lighthouses. The road dead ended at the outlet where water from Grand Lake flows into Lake Huron. The low gleaming sun, the slight warmth in the gentle breeze, the sound of the rocks rolling in the surf—it aligned all too perfectly. I had to stop right there for the day—I had to sit down and just bask in the beauty of the experience. If anything, that evening spent on the beach of Thompson’s Harbor was the defining spiritual experience of the trip. The video encapsulating my experience is included above.

Day 10: Here On Huron

Thompson’s Harbor State Park to Oscoda: 76 Miles

After my euphoric evening at Thompson’s Harbor State Park, I had to follow up with nothing short of a pre-breakfast swim in Lake Huron. My morning route would continue around Grand Lake to the small sleepy enclave of Presque Isle. I would find both the old and the new Presque Isle Lighthouses on a peninsula, and, not unexpectedly, both were closed for the summer. Nevertheless, taking the detour around Grand Lake to those small communities and idyllic harbors was well worth it. After passing another large limestone quarry, I reconnected to US-23 and had a short ride into the city of Alpena.

Alpena hails itself as the ‘Sanctuary of the Great Lakes’ owing to its location at the center of the Thunder Bay National Marine Sanctuary. It is a large city, as far as cities in northeastern Michigan go, and along with the extractive industries of fishing, lumbering, and limestone quarrying, Alpena boats a modest maritime tourist economy as well. Unfortunately the highly acclaimed NOAA Museum and adjoining glass-bottom boat tours were closed due to COVID. At this point in the trip, I had grown terribly tired of the food I had packed from home, so I stopped in downtown Alpena to get the greasiest cheeseburger Alpena could offer. While seated at the restaurant, a middle-aged couple started up a conversation by saying that they had seen me yesterday riding from Mackinaw City. We chatted a while about our Michigan travels, and they seemed thoroughly impressed by my stamina. They also paid for my meal.

I left Alpena headed south on US-23 on the mostly empty road past the endless forest. A peculiar place to stop would be Ossineke, where giant sculptures of Paul Bunyan and Babe the Blue Ox great travelers on the highway. Nearby, a gigantic Jesus holding the earth aloft in one hand beckons visitors to come visit the Dinosaur Gardens Prehistoric Zoo, an eclectic and anachronistic mix of cavemen, dinosaurs, and Christianity. By the time I was ready for a break, I was passing by the small town of Harrisville, and I saw a sign for an outdoor concert at the lakefront pavilion. It was some good foot-tapping folk music being played, and after a few songs an announcement was made that it was the organizer of the concert series birthday today. A homemade carrot cake was cut up to celebrate. I was invited by a women to grab a slice. What great small-town hospitality! South of Harrisville, US-23 travels right next to Lake Huron, on what is called the ‘Sunrise Coast’. In a long stretch from Harrisville to Oscoda, the lake is lined with second homes and vacation rentals. I think I finally found where most of the east-siders go on their summer vacations.

Day 11: To the Thumb Pit

Oscoda to Standish: 71 Miles

The twin villages of Au Sable and Oscoda mark the finish line of one of Michigan’s most epic races: The Au Sable Canoe Marathon. In the race, competitors start 120 miles upstream in Grayling, paddling through the night to reach the finish line near Lake Huron. The race was cancelled in 2020, but seeing so many fine rivers as I biked along the coast made me itch to get out and paddle again.

A short distance later, I would be coming upon the start of the ‘Thumb Pit,’ better known as Saginaw Bay. The Tawas Point Lighthouse marks the start of the bay on the northern end, and Tawas City is a small tourist enclave. Continuing south on US-23, the highway is flat and runs right along the lakeshore. The tourist resorts and second homes disappear, and the landscape consists of forest and utilitarian buildings. Maybe it was something about this road, or maybe it was because I just started to put my head down and ride, but I began to notice an abundance of quarters, nickels, and dimes scattered on the shoulder. Another roadside find was a ‘Don’t Tread On Me’ flag, which was evocative of the region’s independent and libertarian leanings.

Day 12: Thumbs Up

Standish to Port Austin: 77 Miles

Today I would round Saginaw Bay and enter Michigan’s Thumb. Pure geographical curiosity had me wondering what it would be like to visit, though I have heard that the Thumb is very flat, rural, and agricultural. The rumors proved true: the Thumb is incredibly flat, rural, and agricultural. Very small farm towns dot the landscape. Biking south on M-13 going into Bay City, I passed through Pinconning, Michigan’s Cheese Capital. On the Thumb, the town of Sebewaing has a large sugar beet processing plant. It was not until the very tip of the thumb, in the towns of Caseville and Port Austin, where vacation homes and tourist attractions began to sprout up along M-25 by the lakeshore. The thumb-tip also offers a couple of nice state parks with sandy swimming beaches.

Day 13: Last Day Along the Lake

Port Austin to Lakeport: 84 Miles

Starting from the tip of the Thumb, today would be my last day biking along the lakeshore as I made my way south on M-25 towards Port Huron. M-25 runs right along Lake Huron, passing many small towns along the way. Even though the route is right next to a Great Lake, it remains agricultural and undeveloped. I biked past the historical company town of Huron City and then past the Point Aux Barques Lighthouse and former U.S. Life Saving Service Station. I continued biking past many sleepy towns enjoyed by the R.V. crowd, until I passed through more touristy enclaves like Lexington and Lakeport as I neared Port Huron.

Day 14: Eastward

Lakeport to Flint: 96 Miles

Alas, all good things must come to an end, and I was about to wrap up my travels along the Great Lakes and start the long trek eastward back to my starting point in Zeeland. I couldn’t help but say goodbye to Lake Huron with one final swim at Lakeport State Park. From Lakeport I would pedal eastward through the farm country in the heart of the state. I passed through small towns named Yale, Lynn, Capac, and Dryden. The roads were rough and had limited shoulder, and I bet that road bikers are a rare occurrence there. However, even with the unseemingly busy roads and all the trucks trying to get past me, every driver was courteous. By the time I biked to Metamora and Hadley, the farmland had turned to hills and forest. I would end the evening on the outskirts of Flint, after a very long, hot and sunny day.

Days 15 & 16: Wrapping Up

Flint to Middleville to Zeeland: 115 & 35 Miles

One final, scorching hot day was ahead of me as I aimed to make it to my friends Robert and Becky’s house in Middleville for the evening. From the outskirts of Flint, I was immediately back into farm country. I would pass through Durand, home of the Michigan Railroad Historical Museum. I would also pass through Laingsburg, where I began running into fleets of spandexed cyclists out for a Sunday morning ride. Out of Laingsburg, I would follow country roads that ran along the crisp and cool Looking Glass River, being thankful for the trees lining the road that provided some measure of relief from the sun. Once past the outskirts of Lansing, it was all sun-beaten farmland until Middleville. Wanting to avoid traffic, I wandered down country roads, meandering generally East and South towards my destination. While I succeeded in avoiding traffic, I also never ran into the gas station that I had optimistically been counting on to replenish my desperately low electrolytes. By the time I arrived at Robert and Becky’s house, it was well past sunset. An incredibly long day, but one the prospect of seeing old friends again had motivated me on towards.

From Middleville, it was a chip shot of a day to finish the remainder of the trip back to Zeeland. More meandering and country roads, and the unanticipated stretch of country gravel, but 35 miles later I had made the trip complete.