Category Archives: Environment

Chasing Light

It seems I’ve been chasing light lately. First an Austral Summer below the Antarctic Circle. Then a Boreal summer above the Arctic circle. In a few day’s time, shortly after the autumnal equinox has ushered in fall to the northern hemisphere, I will board a plane and fly back to the southern hemisphere for the start of spring. I seem to have become a season hopper.

With three summers in a row without a winter season in between, you’d be forgiven if you thought I was chasing warmth and sunshine instead of chasing daylight. Though astronomically speaking, the seasons have been summer, traditional ‘summer’ weather has been neither what I was seeking or have experienced. Last December I spent the solstice in Antarctica, though even the peak of summer there felt climactically akin to my brethren at home in the Midwest. This June, I was in northern Alaska for the solstice. Yes, temperatures could rise and be unbearable under the full, circling, blazing sun—but it could also become cloudy and reach temperatures within the range of snowfall. Indeed, though the daylight has indicated summertime, these summer seasons haven’t always seemed particularly ‘summery.’

And here I go again, back to New Zealand, back to the southern hemisphere, and back into another summer season. It wasn’t by design that this happened—circumstances and the development of life decisions just produced this unintended result. While working in Antarctica last October through February, I met someone who convinced me to join her on a thru-hike on New Zealand’s Te Araroa trail. So, while the days are short and the snow falls in the northern hemisphere, I will be on the other side of the globe chasing the warmth and summer season as we hike the island together. As we follow the trail from north to south, we will be reaching higher and higher latitudes where in summer the days become longer and the nights are short.

In the temperate mid-latitudes where New Zealand lies, the distinction between periods of night and day are pronounced, but not extreme. But life, as well as the landscape, reaches towards the extreme the more one goes poleward. And beyond the Arctic and Antarctic circles, the land goes from 24-hour sunlight in the summer to 24-hour darkness in the winter. The polar regions are places of extreme seasonal differences. The summer season knows not the winter season, and the transition between the two is abrupt with only truncated springs and falls. From the sun circling overhead continually in the summer, there is only a short transition until the suns sets and never peaks above the horizon in winter.

I have seen firsthand the way the sun wanders aimlessly around the polar summer sky, circumambulating. At McMurdo Station, Antarctica, 77.5 degrees south, I spent 118 days without a sunset. When it finally did occur, the first sunset of the fall was a momentous occasion. The residents of McMurdo piled outside to watch as their faithful sun companion dipped briefly below the horizon, only to rise less than an hour later. And though the sun had officially set, it was far from night, and would be for quite some time. In the beginning of fall, the sun stays so close to the horizon that it remains civil twilight for hours after sunset. Not until a month and a half after the first sunset of the fall does McMurdo experience its first true minutes of night.

With traditional distinctions between day and night becoming muddled at the poles, day and night become somewhat irrelevant. How is one to tell the passage of time when one cannot tell when one day slips into the next? In summer, the sky remains constantly lit. Day rolled into night, but the night seemed just like the day.

In Antarctica, during the summer season, I ended up working the night shift at McMurdo Station. Though the 24-hour clock that the research station ran on considered the shift to be ‘nighttime’, there was no darkness. The only indicator of night was that the throngs of researchers and science support staff hanging out in the galley would slowly subside; there would be a few hours of peaceful quiet while the station slept, until folks began to roll into the galley for coffee and breakfast at the start of another workday. Meanwhile, in those quiet hours in the wee of the morning, the sun was at its lowest angle on the horizon, sending in radiant beams of light through the bank of galley windows—a middle of the night golden hour.

I had no problem adjusting to working the night shift after spending my first few weeks on station as a daytime worker—the sun was as bright as always, and I did not feel like I was sleeping away and wasting daylight as I had felt when I worked overnights for big-box retail. Inside my windowless McMurdo dorm room, the lights were always off. When I needed nighttime, I could retreat to my room and sleep soundly out of the sun. But were I to choose to go out and play instead, the sunlight would be my constant companion.

I had more experience living under the midnight sun this summer, as I led a 50-day backpacking trip north of the Arctic Circle to Alaska’s Arctic National Wildlife Refuge. Our latitude was not quite as high as McMurdo—only at 69 degrees latitude—thus the extremes of sunlight were not as pronounced. But what this trip to Alaska lacked in sheer latitude, it made up for in intensity of experience. Gone were the modern conveniences of McMurdo Station. There was no longer any indoors to hide in, no eternally dark dorm room or dimly-lit dark bar to retreat to. Instead, we were out in the backcountry with no more than we could carry upon our backs. Our only shelter was a thin-walled tent, and the daylight filtered right in. We either made friends with our eyemasks, or we learned to sleep in the light. Once again, the time of day became irrelevant—there was no hiding from the constant presence of the sun.

It took a number of days before I lost the nagging feeling that comes after looking at the late hour on my watch and feeling the pressure to get a hustle on to make camp before darkness falls. Throughout the duration of the trip, I kept tabs of the time on my watch—not out of necessity, but more out of a curiosity of how our circadian rhythms were adapting. Our days slowly dragged out to be longer, as we stayed up later enjoying each other’s company and slept in longer the following mornings. Thus, we ended up being awake through the darkest hours of the day, and even towards the end of the trip after the sun had been setting below the horizon, the light remained with us. Even in the depth of night on our last day in the Wildlife Refuge, it remained light enough in the tent to read a book.

In spite of the mounting fatigue from daylight that comes with constant exposure to lightness, I appreciated the daylight as a benign and amiable companion in a remote and unfamiliar terrain. Here we were, traveling for weeks in the Arctic National Wildlife Refuge, where wolves and grizzly bears roam wild. The signs of these animals were all over—tracks, scat, kill-sites. But the daylight made the wilderness seem friendlier. All told, we saw six wolves and seven grizzly bears on the trip. Seeing the bears and watching their natural disinterested movements in the daylight provided much more psychological comfort for us than wondering if out in the darkness somewhere was a bear lurking just outside the tent.

At about the same time on the trip that I began to miss the creature comforts of home—dry feet and doorways instead of tent zippers—I also began to miss the darkness. Aside from being able to sleep better in the darkness, I began to miss darkness not for darkness itself, but for what it brings to us. The constant daylight drowns out the stars all polar summer long. I’m constantly reminded that people forget this, as I am asked quite often if I saw great stars or aurora. Unfortunately, I was able to see neither stars nor aurora, much to the disappointment of my star-gazing self. And too, having the darkness creep in at the end of the day provides a natural daily cycle of gathering in your shelter for rest. Darkness too, lends itself to gathering around a campfire for light and warmth. Though we did have a campfire on the riverbank one night in Alaska, the magic of the fire just wasn’t the same in the light hours.

As much as I began to miss the darkness, when it finally did come, it felt uncomfortable and foreign. Towards the end of our trip, the nights had been gradually growing dimmer. But right after leaving the Wildlife Refuge, we caught a shuttle ride to Fairbanks, which sits below the Arctic Circle. Darkness descended upon us as we camped in Fairbanks that night. For the first time in nearly two months, it was no longer light enough outside to walk around without a headlamp. The feeling was unfamiliar. Suddenly all the scary feelings of darkness came rushing back in that gut-wrenching primordial fear of the unknown. My how easy it is to forget what darkness is like!

This coming summer, the distinction between day and night will not be as pronounced as I hike the Te Araroa as it was when I spent time closer to the poles. The mid-latitudes will provide a kinder balance of light and darkness each day. Nevertheless, as fall and winter begin to descend on the northern hemisphere, I will once again be off chasing light.

Coronavirus Can Collecting

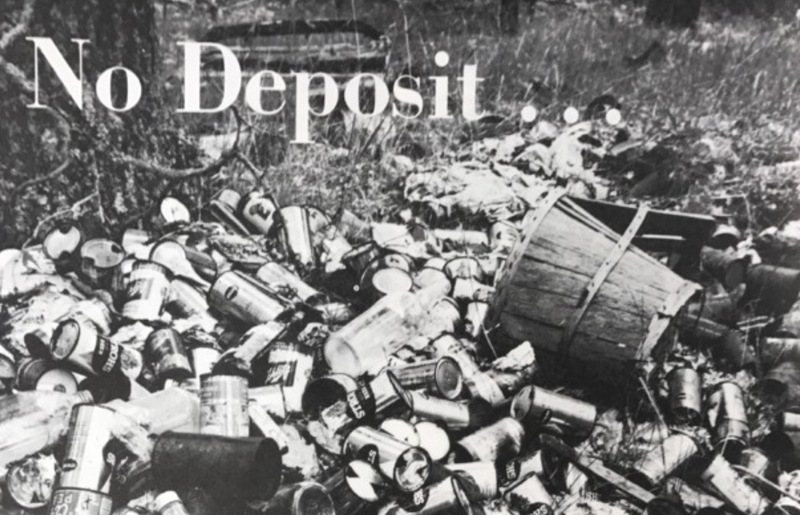

Typical Roadside Litter

A pastime that I share with my father we both affectionately call ‘canning.’ Essentially, the process of canning means either taking a walk or cruising country roads by bicycle looking to collect returnable bottles and cans strewn along a roadside. The benefits of canning are two-fold in that it provides an incentive for outdoors exercise while it simultaneously cleans up the streets of litter. And, thanks to Michigan’s bottle bill, there is a financial incentive to canning as well, which puts a refundable 10-cent deposit on all beer and soda cans and bottles. Though ten cents for a single can may not seem like very much, over the course of an outing it does add up.

With concerns over transmission of the Coronavirus, Michigan’s Governor Gretchen Whitmer ordered all bottle redemption centers closed starting March 24. Automatic bottle returns were not mandated to reopen until June 15, after it was determined that recycling is not a primary driver of disease transmission (in fact, the most dangerous thing you can take into a grocery store during a pandemic is yourself). In the 82 days that Michigan bottle returns were closed, it was estimated that Michiganders collected over $80,000,000 in unredeemed bottle deposits, as the number of unredeemed containers grew by an estimated $7,000,000 each week. At ten cents a pop for a can, that means at one point Michiganders’ had over 800 million cans sitting in their basements and garages! The sheer number of containers alone is staggering, but as a grocery store employee it comes as no surprise as daily I see the overwhelming capacity of beer and soft drinks that are bought and continuously restocked.

Anticipating the impending closure of the bottle returns, I deposited my final pre-closure collection of cans on March 23, just in time for the shutdown. I redeemed a modest sum, a little over $20, which is typical for just a couple weeks of collecting. This meant that during the Coronavirus shutdown, my dad and I would have a fresh start for can collecting so we could visually see just how many cans would pile up on our collection outings during the closure. Even though most grocery store bottle returns had reopened by June 15, the vast number of unredeemed containers created a nightmarish bottle-return backlog. It was not until much later that I finally redeemed all the cans we had collected during the shutdown, mostly due to waiting out the Black Friday-esque rush to redeem cans in the weeks following reopening, coupled with a $25 daily limit on redemption slips. Not to mention that the sheer number of cans I collected would not have even fit in my car (unfortunately, I neglected to take even a single picture of the epic bounty!).

- Not my cans in particular, but you get the idea

It was not until July 8 that I had finally finished returning my three-ish huge garbage bags full of cans. That totals 107 days of collecting. Total value of redemption: $156.20. That equates to 1,562 cans and bottles total! (not to mention all the cans and bottles not redeemed for cash because they were either not acceptable brands or they were too mangled to be accepted by the machine. So this estimate will ultimately be on the low end!).

If we analyze this on a per day basis, this number comes out to nearly 15 cans per day! (14.6 cans to be precise).

Of course, my household did generate some of the cans in our collection. If we subtract our portion of the cans, with a simple estimate of 2 cans per household member per week (we don’t drink a lot of beer or pop), we end up with (15 weeks x 3 people x 2 cans/week/person) = 90 cans, or $9. Not a significant percentage of the bounty (6 percent).

So, excluding my household’s cans leaves 1,472 bottles and cans that were scattered by the roadside, strewn across parking lots, or generally improperly disposed of. In terms of the environment, this is 1,472 pieces of easily recyclable material that instead ended up as unwanted litter!

Michigan’s bottle bill, passed in 1976, put a ten-cent deposit on non-reusable beverage containers. Similar to other environmental legislation of the 1970’s, Michigan’s bottle bill was aimed at reducing trash pollution, conserving natural resources, and increasing the rate of recycling. Among the ten states that currently have bottle bills, Michigan has long had the highest deposit price (being joined only in 2018 after Oregon increased their deposit to ten cents as well). With that higher deposit comes the highest rate of container recapturing: prior to 2018, each year the bottle bill was implemented saw over 90% of beverage containers redeemed. It could be argued that the current trend of falling redemption rates is due to inflation decreasing the value of beverage container refunds; in 2020 dollars, the ten cents paid in 1976, the year the bill was enacted, would be worth about 45 cents today. Perhaps it is time to raise the required deposit to keep up with inflation.

- Scenes like these from the 1970’s inspired Michigan’s 1976 bottle bill

Though Michigan’s recycling rate has fallen slightly as of late, we still lead the nation in terms of container recycling. Unfortunately our national recycling rate is at a disappointing 34.5%, which lags behind many other developed countries. Other states have had trouble passing bottle bills of their own, even though they face substantial litter problems. Tennessee, for example, had bottle bills die in legislation in both 2009 and 2010, even though recycling rates in the state are an abysmal 10 percent and discarded bottles and cans make up the majority of roadside litter. Indeed, the Container Recycling Institute says that beverage containers account for between 40-60% of litter. More states might enact bottle return bills if it wasn’t for the powerful lobbying interests of the can and beverage manufacturers who spend hefty sums to fight such legislation.

So we’ve seen that the ten-cent container deposit in Michigan really does boost recycling rates. But what happens to the deposits on the containers that are never returned? Remember, Michiganders place deposits on approximately 70 million cans each week. Where do the deposits from the 10 percent of containers that are never returned go?

Unredeemed funds from bottle deposits are called escheat funds, and these monies revert to the state. Twenty-five percent of escheat funds go towards retailers to defray the costs of operating bottle redemption sites. The remaining 75 percent of escheat funds goes towards environmental protection measures, which include site-specific environmental clean-up (80%), educational programming on pollution prevention (10%), and deposits into the Cleanup and Redevelopment Trust Fund (10%). The Michigan bottle bill generates around six million dollars each year in escheat funds for the environment.

So every time that you purchase a bottle of beer in Michigan, maybe you should stop and appreciate that the ten cents tacked on to your receipt is helping Michigan’s environment. Not only has the bottle bill increased recycling and decreased litter, it also generates funding for environmental cleanup that is paid for (in large part) by people who litter. Though, as evidenced from the falling rate of container redemption in Michigan, and from my recent collection of 1,472 littered cans, there is still a lot of improvement to do. Michigan could further incentivize recycling by increasing the amount of the required bottle deposit. To combat the abundance of single-use plastic water bottles thrown away, Michigan could consider joining states like Connecticut, Hawaii, Maine, New York, and Oregon that require a deposit on bottled water containers. And another common roadside polluter is liquor bottles; liquor is not included in Michigan’s bottle bill, but liquor containers have a 15-cent deposit in the states of Maine and Vermont. Until society reaches a point where there is no more litter and we recycle purely because it is the right thing to do, my dad and I will continue to enjoy the 10-cent per bottle perk every time we go pick up litter off the roadside.

freshavacado

Seeking Spring Ephemerals

Exploring Van Raalte Farm, a local Holland, Michigan Park

In early spring, well before the trees and shrubs send forth their leaves into the skies above, a fleeting class of plants emerges from the ground to live their brief, wonderous time in the unhindered spring sunlight. These flowers speckle the forest floor with patches of bright whites, yellows, purples, and reds, atop their brilliant fresh green foliage, in a welcome contrast to the subdued hues of winter. The ephemeral show lasts for a few short weeks before the flowers fade away and the lush greens of the plant wither away to wait the remainder of the year hidden secretly underground. In May 2020, I went off as a flower-hunter, spending time scouring a few local parks and preserves in the greater Holland, Michigan area, looking for native wildflowers. I found some ephemerals in bloom, was too late on others, but everywhere saw a diversity of early-blooming wildflowers. I encountered a much greater floral diversity than I could reasonably post here—so get out to your local parks and go seek your own wildflowers!

A sure sign of spring in the forest are the large brilliant blooms of the Trillium (Trillium grandiflorum) Melantiaceae. Single stalks with leaves of three and flowers with petals of three (it is the TRI-llium, after all). The showy white flowers gradually turn to pink.

A personal favorite of mine is the swaths of Trout Lilies (Erythronium americanum) Liliaceae that blanket the forest floor. Bright yellow lily-like flowers nod from a stalk that emerges above their one or two leaves. Brown mottling on the leaves is said to resemble the skin of trout, giving rise to the plant’s common name. Their peak bloom in West Michigan is in April, but I was fortunate to catch a few late flowers in May.

Forming dense clusters of large, deeply-cleft umbrella-like leaves is the Mayapple (Podophyllum peltatum) Berberidaceae. The fleshy stalks emerge in April, and a single white flower blooms in May. The ‘apple’ that gives the plant its common name (also called a ‘forest lemon’) does not ripen until June, and all green parts of the plant, including the unripe fruit, are poisonous.

Found abundantly in wet, marshy areas is the aptly-named Marsh Marigold (Caltha palustris) Ranunculaceae. This bright-yellow flowered plant grows in colonies and steadily blooms from April to August.

Another bright yellow flower, although this one with only a single bloom and being found in more upland the woods is the Hispid Buttercup (Ranunculus hispidus) Ranunculaceae. The word ‘hispid’ means covered with stiff hairs or bristles, and references the flowering stalk of the plant.

Dense colonies of 5-sepaled flowers growing up to one foot high in woodlands is an indicator of the False Meadow Rue (Isopyrum biternatum) Ranunculaceae. A true spring ephemeral, False Meadow Rue blooms for only a few weeks in May, then completely withers away to its roots.

Another flowering plant of moist woodlands, this one purple in color, is the Wild Geranium (Geranium maculatum) Geraniaceae. The geranium is popular with gardeners, and several domesticated varieties can be found in cultivation.

An incredibly brilliant and uniquely-shaped flower is found on the Wild Columbine (Aquilegea canadensis) Ranunculaceae. Several flowers, with five red-spurred petals and protruding yellow stamens, hang from the plant above its deeply lobed leaves. Nectar is stored in the flower’s spurs, providing food for pollinating hummingbirds.

Multiple globe-shaped clusters of tiny white flowers emerging from a single stem on the forest floor indicate Wild Sarsaparilla (Aralia nudicaulis) Araliaceae. Not far from the flowering stem are the leaves of plant, deeply divided into typically 5 leaflets. Young Wild Sarsaparilla with three leaflets and a glossy purple hue can sometimes uncannily resemble poison ivy. The roots can be used as a substitute for real Sarsaparilla flavoring, though the plant is not closely related to the True Sarsaparilla (Smilax sp.) of tropical climates.

A single palm leaf-like plant with a spiked cluster of small white flowers is the False Solomon’s Seal (Smilacina racemosa) Asparagaceae. It grows in the same habitat as the true Solomon’s Seal (Polygonatum sp.), which will have several bell-shaped flowers hanging under the stem. The origin of the common name ‘Solomon’s Seal’ is unclear, though it was perhaps named in reference to the plant roots resembling a signet ring or Hebrew characters.

Not only were the wildflowers blooming, but some trees were in bloom too. I came across this small native understory tree, the Eastern Redbud (Cercis canadensis) Fabaceae. The Redbud blooms profligately with bunches of pink flowers, making it no wonder it is popular as a landscape tree as well.

Showing promise of fruity treasure to come in June is this diminutive white flower, Wild Strawberry (Fragaria virginiana) Rosaceae. Wild strawberry plants sprawl across sunny open patches by spreading with runners. The thimble-sized strawberries are juicy and flavorful, and are quite popular with this flower-hunter.

The field guide I used in identifying these plants was Newcomb’s Wildflower Guide © 1977 by Little, Brown and Co.

Hi!

Everyman’s Right

In many European countries, particularly Northern and Eastern Europe, there is a modern culture and deep history of rambling around the countryside in uninhabited or pastoral lands, regardless of the ownership status of the land—whether privately or publicly held. This ability to freely roam and travel comes with an implied responsibility for the user; wanderers have an ethic to keep—to act courteously, to not disturb the land-owner, and to refrain from exploiting the land or its resources. The travelers have to leave no trace of their passing through, save for the beaten paths of the various travelways that develop along common routes. This freedom—this right to travel—provided a means for the landless commoners of European society to travel and recreate, and neither were landed classes excluded from such benefits of access. The freedom to travel dates back to antiquity as a right of the masses. It survived medieval feudalism, it endured the changes wrought by the industrial revolution, and it thrives today in modern European societies. Known by various different names in their home countries, the common translation for this freedom is the ‘Everyman’s Right.’ Alternatively known as the ‘right to roam’ or the ‘right of public access to the wilderness,’ the Everyman’s right provides every man (as well as every woman) the right to free movement on lands and waters for leisure or recreation.

The European land model of access (or sometimes in-access) developed based on feudalism and the lands known as the commons. In the feudal system, feudal peasants—i.e., the commoners—had property rights to small plots of land only when they were actively being cultivated. Once the crops had been harvested, the land reverted to being part of the commons. In general, the commons were lands that were commonly held by the people, and could thus be exploited by anyone for subsistence or for economic gain. Commoners could graze livestock or harvest plant resources from such common land within established feudal limits, just as well they could freely travel and recreate on such land. However, starting in England in the 15th century, manorial lords sought to increase their harvest of crops and thus began a practice of enclosure, whereby common lands were enclosed by hedgerows (primitive-day fencing) as a means of keeping the common benefits to themselves permanently. The act of enclosure removed the commoners’ access to benefit from the land resources economically, as well as creating a physical barrier for public access. Land enclosure progressed steadily in England until the late 1800’s when the start of the industrial revolution provided a momentum-boost for enclosure; just like the mindset of the industrial revolution, latter-day enclosure was commenced to create greater agricultural efficiency in production. The practice of enclosure eventually spread to continental Europe as well, and by the end of the industrial revolution, most enclosure on the continent—particularly Germany, France, and Denmark—was complete. The commoners of Europe found themselves displaced from the rural landscape and largely forced to migrate to large cities to work in the centers of industry. Though enclosure forced the end of commoners being able to benefit economically from common land, the practice of traveling through common land was retained as it was historically as a right to free movement. In modern Europe today, since the rise of the leisure class has given ample recreation time to the masses, the right to roam underpins the concept of using privately held lands for personal recreation. Though historically a de facto right, the Everyman’s right has only recently been formally legalized as a wave of European countries codified this practice into protected law, starting with the Nordic countries in the 1950’s and more recently with countries in the United Kingdom in the 1990’s and 2000’s.

I have never been to Europe. I have never gotten to practice the Everyman’s Right as it is the culture on that continent. Instead, I live in America where a different land access model developed. Unlike Europe, where residents lived since antiquity off the commons until the commons were enclosed, most American lands were systematically surveyed, partitioned, and essentially given away for free to private citizenry by a strong federal government all for the sake of rapidly settling this expansive country. And the land seemed inexhaustible in the early days of our nation. The outlook at this time by these Euro-american settlers and their government was that these lands were empty and owned by no one, free for the taking for whoever could claim and settle them (never mind the cruel fate of history where indigenous peoples were forced from their ancestral lands, often violently). Private property ownership was a draw for those European immigrants, displaced by the land reforms in the industrial revolution, who wanted land of their own and could find it plentifully in this country. And unlike Europe, where the commoner’s right to travel across land was respected, private property in America developed with the right—indeed the expectation—to exclude others from accessing their privately held lands.

It was not until some visionary leaders around the turn of the 20th century decided that America should hold back some of its lands from settlement to instead be held in the public trust for the good of the people. The influential works of these leaders included the environmental prophecy of John Muir, the scientific land management principles of Gifford Pinchot, and the political resolve of Teddy Roosevelt. John Muir, perhaps America’s greatest wandering vagabond, had a philosophy about land access that reflected his wanderlust-filled Scottish heritage and his first eleven years of life spent in Scotland; Muir’s penchant for free travel would be the underpinnings of his advocacy for recreational travel on wild lands. Political figures like Roosevelt and Pinchot worked to create the Forest Reserve act of 1891, which gave the president sweeping power to set aside vast swaths of public domain lands as forest reserves, and the Antiquities Act of 1906 which granted the president power to preserve public lands deemed as significant archaeological or public resources. These reserved lands would later become our national parks and national forests, the crown jewels of our public land system. As of today, approximately 27.4% of the United States land area is owned by the federal government, primarily administered by four large land management agencies: the Bureau of Land Management, the U.S. Forest Service, the National Park Service, and the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service; many other agencies also manage smaller parcels of public land. These lands are held in the public trust for the “greatest good for the greatest number for the greatest time (Gifford Pinchot).” When Pinchot uttered those words, however, his intent was for the economic good of the people based on conservative resource extraction. Recreation on public lands as a good in and of itself, and as a governmental priority would not develop in earnest until post-WWII.

Federal Public Lands in America. An astute observer will notice that lands administered by the Bureau of Indian Affairs are shown. Though owned by the federal government, these lands are held in trust for the tribes and leased to individuals in the tribal nations. These lands thus are not universally publicly accessible. Similarly, Department of Defense lands are also shown, which have restricted public access. Lands managed by both agencies constitute a small percentage of all federal lands.

As landlord, the federal government makes the laws and regulations pertaining to the use and access of public lands. The vast majority of these lands are open to the public for travel and recreation with few exceptions (see text in the above graphic); the public is free to use and enjoy these public domain lands usually free of charge, or sometimes with a small fee to cover land management costs. As an American proud of the natural heritage of my country and in admiration of the earlier efforts of the heroes to preserve it for the perpetuity of the generations, I look at my nation as a shining example of preserving lands for public use. I am proud at how over a quarter of my country’s area is protected for the good of the people.

But as proud as I am of America’s public land resources and as much as I have enjoyed them first-hand, there is a great and obvious disparity in geography. While more than 27% of America lies in the public domain*, 96% of this land area lies in Alaska and the 11 western states. That means that just four percent of federal lands are shared among the remaining 38 states. This includes states like Connecticut and Iowa where only 0.3% of the state’s land area falls under the purview of the federal government, and thus free public access is limited to those small holdings of land. And, even though the majority of the land in the Western United States is public, not all of it is accessible due to private property rights. Public lands in the west are often interspersed in a matrix of private land ownership, preventing access to some lands in the public domain. Nowhere is this more apparent than in the ‘checkerboard’ lands which resulted from governmental land grants to private corporations in the 1800’s.

There is an obvious geographic disparity when it comes to the distribution of federal public lands.

The ‘checkerboard’ landscape. It’s not hard to guess which of these square-mile land parcels are publicly owned and which ones are in private hands. Due to trespassing laws on private land, the checkerboard lands, though public, are largely inaccessible.

As a Midwesterner, growing up in a landscape of privately-held farm and forest parcels, I am used to a paucity of large expanses of public wildlands. But drawn to where the public lands are, I have spent abundant time exploring our public lands in the western United States. My latest trip in the west, my 463-mile canoe trip down Wyoming, Colorado, and Utah’s Green River, put public land access on the forefront of my mind once again. Though I’ve studied federal land policy quite a bit in college, nothing puts such study directly into practice like trying to plan a long-distance river expedition over a matrix of public and private lands.

Enshrined in the United States Constitution, under Article 1, Section 8, is the Commerce Clause, which establishes the doctrine of Navigable Servitude. The Commerce Clause establishes that the United States Federal Government holds the property rights of all the navigable surface waters in the United States, and Navigable Servitude stipulates that these waters be held in the public domain for the sake of interstate commerce. Later case law—in a 2013 decision by the 4th Circuit Court—determined that paddling is not a federally protected right. Yet, where not specifically prohibited by law, boating is an acceptable action on public waterways. The land underlying the surface of navigable waters, however, does not fall under the purview of the Commerce Clause, and as such is able to be privately owned. Thus, on my Green River expedition, so long as I was paddling on the surface of the river, I was on public property.

The challenge of a long canoe trip, though, is that a paddler can’t spend the entire time canoeing. Eventually you have to land to take care of basic biological needs and to rest. On the Green River, in the very upriver-most sections where the river flows through the Bridger-Teton National Forest (i.e., federally-owned public land), it was easy to paddle the river and always land on public domain lands which were open to recreation. But once the Green left the National Forest, it entered a matrix of publicly and privately owned land, and in those upper reaches there were long stretches of river with no access to public land. Wyoming state law extends private property ownership rights to the land under the river itself (remember, the river itself is federally owned). So every time I stepped my foot out of my canoe, I was technically trespassing!

Fortunately, with me through this challenging mosaic of private land was my ever-heedful friend Jon, who is extraordinarily conscious about not trespassing. Though along this stretch of river we saw few people and even fewer buildings, most of this land was still privately-held rangeland. Whereas I personally had fewer reservations about stopping to rest on an isolated cow pasture, Jon was adamant about not infringing on the property rights of others. Though it was a constant challenge and concern, we were able to find parcels of public domain lands every night to camp on. And thanks to the tone set by Jon’s vigilance, all 24 nights I spent on the river ended up being on some sort of pubic domain land. In these areas, the federal lands fall to ‘shared-use’ management policies, which meant that grazing interests had a right to use the land for economic exploitation just as much as I had a right to use the land for personal recreation; the result was that my campsites were often shared by grazing cattle. Identifying the federal land in the upper stretches of the Green River proved not to be too difficult either; while the majority of the river corridor was flat rangeland, there was the occasional steep, unvegetated butte that always lined up perfectly with the land ownership boundaries. These public lands were of those administered by the Bureau of Land Management, colloquially known as ‘the lands that no one wanted.’ Paddling down the river, it was easy to see why certain land parcels ended up in the public domain.

In the headwaters of the Green River in Wyoming. Take a guess as to what land in the picture belongs in the public domain.

On my Green River Expedition, I successfully spent each night camped on federal or state land instead of on private land, which is a small moral victory in terms of doing things legally. However, the view from the ground showed little distinction between public and private lands. Sure, there were a few derelict fences marking boundaries. But cattle grazing occurs on both public and private land, and little to no structural improvements were seen on the private land along the course of most of the river. The type of place the Green River flowed through, even if it was completely private land, would have been such that I would have felt comfortable traveling and camping on such land despite its private ownership status. If the Green was a European river, it absolutely would have been the kind of place where recreational access would have been granted under right to roam laws.

In America, where right to roam laws do not exist, I have had to practice my own right to roam access where public lands are not as plentiful. I try to avoid this whenever possible, but the few occasions I have resorted to this self-granted right have been on biking or hiking trips in the eastern U.S. where sections of private land are expansive and public resources hard to find. Instead of benefiting from a universal right to roam granted by the United States government, I call my practice guerrilla camping, where I bed down for the night hidden away on private land. My knowledgeable and intentional trespass onto private property is not done without its own moral code, however; akin to the ethics codified in the Everyman’s Right, I camp as far away from development as possible, do no damage to the land, and leave no trace of my ever being there. In the few dozen times I have had to resort to guerrilla camping, I have never been caught in the act, and I remain doubtful that the landowner is any wiser to my being there. It is my own first-hand experience that an Everyman’s Right is feasible in America.

Finding public land to camp on in agricultural Illinois is a bit tricky

But Americans still have certain attitudes towards private land ownership and its use that is not shared by their European counterparts, particularly where the freedom of passage is concerned. In America, where private property ownership is a near-virtue, we think about possessing the land. We take the libertarian stance that we are free to do as we like to our private property. But we don’t often think about the limitations that are already placed on land ownership; environmental laws and building codes all limit a land-owners freedom to dig a strip-mine or to build a citadel on their land. At its essence, private land ownership is not so much the physical possession of the physical land itself, but a bundle of rights of what one can do on and to the land. For example, private property rights entitles the land-holder to the rights of harvesting plant, animal, and mineral resources found on the land for economic gain within existing legal regulations; likewise the land-holder has the rights to modify the land and to make improvements on the land itself within the bounds of civil building codes. In America, also included in this bundle of property-owners’ rights is the right to exclude others from one’s property. This right sets up a system where trespassing becomes possible and punishable on private lands; this property right to exclude others is often the first right that comes to mind when an American thinks of private property. In European countries, where there is a traditional right to roam, the right to exclude others from property is not a right conveyed by private property ownership.

To the American mind that is accustomed to the notion of private property being the physical space where one can exclude others, the ability to limit the access of others is held sacrosanct. And, it is incredibly easy to distrust others and fear for the worst of what might happen if the right to exclude others from private property is out-legislated like it has in Europe. However, the code of ethics built into the Everyman’s Right legislation should alleviate fears of lawlessness and mass trespass should an Everyman’s Right be passed in America. Everyman’s Right legislation specifies limits to the right of public access. Access to lands and waters are generally only permitted for non-motorized recreational uses such as walking, cycling, and horseback riding. Camping on private land is limited to one night in most places, and most laws specify a certain distance that any recreational activity is to have away from homes, structures, and maintained lawns and gardens. Excessive noise is discouraged and most fires on private property are forbidden. Visitors are in general restricted from harvesting plant and animal resources that are found on the land, and visitors are encouraged to stick to existing pathways while on private property. Lands that can be ecologically damaged or sensitive croplands are also excluded from this right to travel. While the rights and responsibilities codified in these right to roam laws vary according to the specific country, the general theme is to allow public access while limiting infringement upon the property-owner’s rights. Just because the public gains access to your land doesn’t mean they are automatically permitted to start camping in your front yard and harvesting your vegetable garden.

Fortunately there is progress in America as states and localities are gradually making moves towards this more European-style right to roam land ethic. Coastal states like Oregon, California, and Florida have made much, if not all, of their coastal lands and beaches free to public access. States are also passing liability legislation to reduce land-owner liability for injuries sustained by other parties while on private land; such legislation is designed to encourage landowners to open up their land to increased public recreational access. Many non-profit organizations, such as the Land Conservancy, are working with private land owners to grant public access to private lands through conservation easements; such easements are one big step toward allowing limited public access while maintaining the rights of private landholders. As Americans, we cannot rely solely on our legacy of federal public land protection to provide wildland access to all the people in our country. We must continually seek to make free access to land a priority. On the Green River in Wyoming, despite the riparian zone being privately owned, many easements have been granted by private landowners along the river to permit the use of fishing access. It is a good step for ensuring equitable access to our nation’s land and water resources.

I would like to see the day when the United States adopts its own right to roam legislation. I would like to see a future where everyone, regardless of where they live, will have access to travel through our nation’s wild lands. I would like to be able to travel and roam myself and not have to worry about breaking trespassing laws when looking for a place to camp for the night. Until the time comes when America adopts its own right to roam law, we ought to start re-envisioning the greatest good for the greatest number for our privately held lands as well as our public lands.

*Additional public lands exist at the state and local government level, which get excluded from this analysis which focuses on federal lands due to various public access differences and due to lack of statistics on other public lands distribution.

Vegetarian for a Summer

Recently I completed a challenge with another friend, where, for a summer only, I would lead a vegetarian diet. Though the duration of the challenge was short in the scheme of life, it was still substantial enough a time to get a glimpse of what it’s like to be on the vegetarian side. I completed this challenge while working at the Adventure Trips program at camp, where I was responsible for planning and cooking meals with a group of up to 12 active teenaged campers. Thus, my vegetarian diet was lived in the context of daily sharing meals with others, and faced both the benefits and difficulties of communal food.

The summer transition to being ‘officially’ vegetarian was not hard to make for me. In general, my meat consumption has been pretty low ever since my junior year in college when I shared a house with six vegetarians. Learning to cook for myself in this household, I became accustomed to making a variety of satisfying dishes using just vegetables. In the years following, I seldom bought meat for myself, and just as often I would consume meat I salvaged from a dumpster. Bacon, perhaps, was my most commonly used meat, but only as a spice and not as a meal. On the infrequent occasions I would visit a restaurant, I did freely order and partake of meat on the menu, and I also would eat meat when it was served by company. Otherwise I lived a near-vegetarian lifestyle.

So what was my motivation to undergo this challenge for the summer? Part of it was just to see if I could completely do it—that, and the curiosity of what would happen if I did abstain from meat for so long. But when talking about vegetarianism, it seems common that others will want the vegetarians to justify the rationale behind their food choices, as if only vegetarians are to be held accountable for the reasons they eat the foods they do. Though many people go vegetarian for health reasons, this was not one of my reasons; I am convinced that meat can be a healthy part of a balanced diet. Many people also go vegetarian out of a compassionate welfare for the animals themselves. Again, this was not part of my motivation for going vegetarian. Biologically speaking, animals must die and be eaten in order for the ecological world to continue on, and humans have long participated in the tradition of eating meat as sustenance. Though I do not feel that it is immoral to consume animal products, I do feel like if you do consume meat, then you should be willing to see where it comes from—if not even kill it and prepare it yourself. Though a vegetarian this summer, I did watch in vivid interest as one of the camp’s chickens was cleaned and butchered. The transition from live animal to food is an interesting one, and one that not many people get direct experience with—meat-eaters included.

If there was an underlying motivation for my low meat consumption in the past, and for me to try the completely vegetarian lifestyle this summer, it would be environmental. This was my attempt to eat lower on the food chain, and thus limit the impact my diet has on the planet. Factory farmed meat, as it is produced commercially in the developed world, is resource intensive and wasteful. More energy goes into producing animal proteins that could more efficiently be converted into plant foods. This wanton use of resources—a byproduct of our cultural desire to have meat readily and cheaply available—contributes to even greater environmental degradation. Plus, this industrial scale meat system comes with the added externalities of increased chemical and antibiotic use, greenhouse gas emissions, land-clearing, animal mistreatment, and the like. In sum total, cheap meat comes at a high price. Becoming a vegetarian for the summer was my way of exempting myself from the corporate meat system. Perhaps, idealistically, just by reducing my demand for meat, the system will begin to change to offer more sustainable alternatives

So how challenging was going vegetarian? Overall, not too bad.

As mentioned above, it was not too hard of a transition to make practically. Being used to eating mostly vegetable dishes, I was able to feed myself and survive the whole summer. I found that I actually didn’t miss meat that much, if at all. Rummaging through the fridge for leftovers as I commonly do, if I saw a container full of meat, it actually began to look unappealing to me. True, the smell of freshly fried bacon did always tempt me, and I did eat a slice of pepperoni that fell on the ground. Otherwise, my vegetarian commitment was not terribly difficult to keep.

The more challenging part of vegetarianism was psychological. It was a challenge to see my identity as a vegetarian. Nor over the course of the summer did I ever feel that I realty owned up to the label either. When I had to explain my dietary restrictions to others, I would always try and qualify my vegetarianism: “it’s only temporary,” or “it’s just a challenge I’m doing over the summer,” I would say. Never was I just Ty the vegetarian. I was Ty the vegetarian*. But although it was difficult to apply the label to myself and feel authentic about it, it was easier when others applied the label to me. Campers at summer camp somehow found out without me telling them, and they would thus call me a vegetarian on their own initiative. Knowing me for only a week at a time, vegetarian Ty was the only side of me they ever knew, so they never questioned me about my transition to it. So only once other people started calling me a vegetarian and asking me all kinds of curious questions about what it is like, did I finally come to start feeling like I too could own the label. Nevertheless, I never fully felt authentic as a vegetarian, since my endeavor was only temporary and experimental. Though there is not just one kind of vegetarian, I never felt like I could fully own the label and subscribe to the identity politics of vegetarianism.

Additionally, and somewhat expectedly, being a vegetarian also made me think about food options a whole lot more. Previously, as a food opportunist and a not too particularly picky eater, I didn’t think about what exactly I was eating with a whole lot of thought. Back then, so to speak, all options were literally on the table. If it was edible, then why not eat it? But I found that excepting myself from any carnivorous partakings made me dwell on the limits of what I could and could not eat. Instead of always being assured of having enough food, I started to worry if there would be enough vegetarian options left over for me to eat; sometimes there were not, and I had less than my desired fill even when there were plenty of meat options left over. For perhaps the first time ever, I also found that I had to be a staunch advocate for my food as well. I don’t really like to make a fuss over food things, especially since I’ll eat just about anything. But this summer, in order for me to make sure there would be food for myself as well, I had to advocate for a non-meat option at each meal. This was challenging at times, especially because I often felt like a ‘fake’ vegetarian who was just being ‘picky’ about meat. Add to that, I’d much rather not encumber or inconvenience people by adding more dietary restrictions to the chefs, especially when I was the only professed vegetarian partaking in a meal. But at the same time, if my rationale behind going vegetarian was environmentally based, then causing a fuss at meal times would be a start to greater change. Abstaining from meat at one single meal might not seem like it makes a lot of difference, but it does work to challenge the assumption that every meal must contain meat. After continual meal-time fuss, eventually less meat will be demanded and ordered per meal, and the negative environmental impacts will diminish with it.

Unfortunately, though my rationale for going vegetarian was environmental (i.e., to reduce waste associated with food), going vegetarian seemed to have unintentionally increased my personal food waste. When defining the terms of the vegetarian challenge at the start of the summer, my friend and I both agreed that ‘Trash Meat’—that is, meat that was going to be thrown away anyway—would be within the bounds of our vegetarianism. Though Trash Meat was fair game, I felt like it would be cheating to partake of it. Rummaging through the fridge for leftovers, I often came across containers full of good, edible meals that just happened to have a little bit of meat mixed in. Out of vegetarian principle, I avoided consuming those leftovers. And, as my niche at camp was to finish off all the leftovers, those containers of food continued to sit in the fridge untouched until the food inside spoiled. Whereas previously I would have eaten a meal and simultaneously reduced food waste by eating other people’s leftovers, I was instead inclined to throw the food out. I began to realize that meals are more accommodating to all when the meat is served on the side, and not mixed in with the main dish. Thus, it would be less wasteful if meat were an opt-in thing, rather than an opt-out thing.

Now that the summer has ended, my commitment to being a vegetarian has elapsed. What has happened since that time? Well, I’ve gone back to the pattern of food consumption that I previously was in, where no particular food item is off limits. I have eaten meat again—though primarily meat leftovers. I still don’t eat a lot of it, but I’m a food scavenger at heart. If I can save a food item from getting thrown in the trash, whether it has meat in it or not, isn’t that the better option anyway? I’m fine leaving the label vegetarian behind too. I never felt fully comfortable with that label anyway. But overall, I will continue my commitment to eating low on the food chain and to reducing my environmental impact in whatever form that takes, whether it be going completely vegetarian again in the future or continuing to eat trash meat out of the dumpster. Perhaps a more suitable label for me other that vegetarian would be freegan.

As a timely thought-piece during my experiment, NPR published an article about how an all-vegetarian world is not necessarily a better world—or even a practical world. In any case, mindlessly consuming any type of food without thinking broadly about its impact is the worst way to go. Perhaps all it does take to make a positive change towards a more sustainable food system is a group of people who want to challenge the status quo by saying ‘no I don’t want your industrialized meat’. Vegetarians have their place, but it is not for only vegetarians to make a difference in the food system.

Killing for Ecology

I’ve been on a killing spree lately. No rampant caterpillar can escape from my smash…or at least my smashing ire. I’m conducting this purge because I’m an environmentalist. Ecology has turned me into a cold-blooded killer.

The standard picture of an environmentalist is often the gentle, peaceful hippie type, someone who expresses tender loving care for all plants and animals on the planet. They are caricatured as supporting all life and opposing all death and violence. As such, killing is not even remotely imagined as a tool that is in the environmentalist’s repertoire; in fact, it may be thought of as the antithesis. But the ecological household of nature operates differently from idealized notions of harmonious environmentalism. As the poet Tennyson would say, nature is ‘red in tooth and claw’; death, as well as life, are integral parts of nature. It is an eat or be eaten type of world, and death is as necessary to nature as every organism’s metabolism. Nature continues on unceasingly because it rests in an appropriate balance between the processes of life and death, fecundity and consumption. But unfortunately, the balance of nature can readily be tipped to a point of drastic change; there exist certain species that can escape their native habitats and alter the balance of the ecosystems in which they land. These species are known as non-native invasive species. Environmentalists and ecologists alike are thus faced with the quandary of whether it is right—and to what extent it is—to kill in order to restore the balance to native ecosystems.

One of the cast of characters that appears on the most harmful invasive species list is the gypsy moth (Lymantria dispar dispar). This innocuous little caterpillar—and its flightless adult moth—seem relatively benign singularly, yet the monstrosity of their sheer numbers has been an extreme detriment to the northeastern United States. Native to Europe, the gypsy moth was intentionally brought to America less than 150 years ago in 1869. A man by the name of Étienne Léopold Trouvelot imported the non-native moths with the intent of interbreeding them with silk worms to develop a more resilient silkworm industry. Trouvelot’s experiment inevitably failed, and whether intentional or not, the moths were released from his residence just outside of Boston. Lacking any of their natural predators to keep their population in check, just twenty years later the first major outbreak of gypsy moths occurred in Massachusetts. Trees were defoliated, caterpillars covered everything, and frass (i.e. insect excrement) rained down on the town. Since then, the gypsy moths have started on their relentless march across the northeastern United States. Each year, the gypsy moths stake claim to new habitat, and with it they bring their trail of destruction. Entire sections of forest can be defoliated in an outbreak scenario, and the creatures can easily defoliate more than a million acres of hardwood forest in a given summer.

Spread of Gypsy Moths in the United States, 1900-2007 (compiled by US Forest Service)

In early May, the next generation of gypsy moth caterpillars hatch from their over-wintering egg cases and commence their feast. They emerge by the millions and coat everything en masse. The tiny black-haired little crawlers make their visual appearance when they are about an eighth of an inch long, appearing on every natural or human-made object outdoors. The tiny caterpillars spin an elongated strand of silk and their long spikey hairs allow them to get carried by the wind to new places. To the casual observer, it seems like the tiny creatures are flying around. A young gypsy moth hopes to land on a palatable tree so it can begin its banquet and increase in size; barring an ideal landing zone, the caterpillars have a relentless drive to crawl over any obstacle to find a food source. In late spring, the observer can tell once again when the caterpillars have returned and can thus take action before much damage is done to the ecosystem. When the caterpillars are small, they are easy to destroy. Squashing the pests seems inconsequential. Pressing down upon them with a thumb produces nothing but a small black smear. Each caterpillar dispatched is gone forever and its life and memory are no more.

In early May the small gypsy moth caterpillars emerge and coat everything in sight.

But as the creatures grow, they become harder and harder to kill both physically and psychologically. They have been feeding for weeks, turning native plant leaves into more gypsy moth biomass. The caterpillars have become larger, less fragile creatures. When they reach half an inch long, they are sizeable enough to squirt out a blob of dark-green or bright-yellow juice whenever they are squashed. At an inch long, they begin to display an adverse reaction to being squeezed; it takes increasing pressure before the caterpillar is popped and its life juices run down the leaves. As the caterpillars keep growing larger, their features become more distinguishable; they have become stronger and actively resist death now with all their might. Killing the destructive organisms is now more of a struggle, particularly a psychological battle for the executioner. The juice that gets on one’s hands sometimes runs a deep red, reminding the slayer that it once belonged to the realm of the living. The breached corpses of the caterpillars clench indefinitely to their leaves even in death, a chilling reminder of the life that once was. These things remind the exterminator that the organism dispatched just moments ago was a living, moving creature.

Older gypsy moth caterpillars in the act of defoliating an apple tree.

What right do I have in taking a fellow creature’s life? Especially if they cause little direct harm to me? Is the fate of the ecosystem dependent upon my action as a concerned ecologist? Or should the gypsy moths be left alone and nature allowed to run her course? As the gypsy moth caterpillars grow, they continue to become more and more of a nuisance, even reaching plague proportions. They feverishly eat leaves, turning the native oak trees into Swiss cheese. Infestations can defoliate entire trees and can even lead to tree death; entire sections of native hardwood forest can be denuded by these insects. In a quiet moment in the forests of New England, the very sound of destruction can be heard from the tree-tops. Close your eyes and listen—it is not a sprinkle of rain you are hearing, but the falling frass of the swarm. The oak trees, and other hardwoods, suffer at the mouths of these non-native herbivores. The other native creatures that depend on the forests for food and habitat are adversely affected too. The greed of the gypsy moth’s appetite knows no bounds. Is it thus justified to kill the caterpillars for the sake of the trees and the forest in general?

The damage done to an Oak tree, the gypsy moth caterpillar’s favorite forage.

Should we as humans intervene in the situation of invasive species, even if it means the prescribed death of millions of organisms? It is a struggle that we as environmentalists and modern humans must face. Our civilized world has created a narrative that removes us from the brutal truth of ecological relationships and our impact on the natural world. The metabolism of life is neatly tucked away into the folds of textbooks or of the grocery store. We do not see where our food comes from, and we avert our eyes to predation in nature. We do not fully respect the fact that in order for the balance of nature to remain intact, life indeed must be taken. Death has become so unpalatable to our modern culture. It is thus exceedingly difficult to compromise a human distaste for killing with a commitment to the facts of ecology. I am both an environmentalist and an ecologist, yet I too struggle with the necessity of death. Humans are compassionate and sympathetic beings. It is hard to watch a young or injured animal die. We like to root for the underdog to survive. But not every organism in an ecosystem ever survives; it is not even physically possible for every organism in an ecosystem to survive. The balance of nature rests on the facts of metabolism—of life and death. When humans are responsible for bringing the balance of nature to a tipping-point, shouldn’t we also be responsible for correcting our wrongs? Isn’t killing another organism justified in the name of the ecological integrity of the whole system?

I encountered a similar moral dilemma surrounding the eradication of an invasive species when I was in Australia—only this example was more extreme. Instead of simply squashing caterpillars, the most-wanted organism was the cane toad. These creatures were much more relatable than a small caterpillar, and the moral qualms surrounding their eradication were much harder for me personally. The cane toad, a vertebrate, is much more closely related to human kind. Its blood and organs are similar to mine, and I felt as if I had some kind of evolutionary connection to the toad that I didn’t share with a caterpillar. Cane toads are also much larger—reaching up to the size of a dinner plate, and their deaths would prove all the more gruesome because of it. Though I knew intellectually how disruptive the cane toads were to the ecology of Australia, I individually had quite a few reservations about personally killing a cane toad.

Cane toads (Rhinella marina) were introduced to Australia from the tropical Americas in 1935 as a biological control method to combat the cane beetle, which was threatening Australia’s sugar cane crop. In 1935, 102 toads were released in agricultural areas in Queensland. From then to now, cane toad numbers have increased to more than 200 million in Australia today. Adding insult to injury, the introduced cane toads did not even control the cane beetles they were intended to ingest. Instead, cane toads wreak havoc by gorging themselves on native Australian fauna, eating native creatures directly and leaving less food for other native species. Additionally, the cane toads are highly poisonous and use their poison glands as their primary defense mechanism. Native Australian fauna, unfamiliar with the toads, see the meaty morsels as an easy meal. The cane toads do little to resist being bitten, and instead wait for the poison excreted from their skin to kill the pursuing predator. Instead of an easy meal, the Australian wildlife is poisoned to death. As the cane toads continued to hop into uncharted territory in the Australian bush, more and more native wildlife became diminished because of it.

The massive (and massively destructive) cane toad.

Cane toads have become a much bemoaned villain in Australia, and the culture Down Under is unsympathetic to the toads. Aussies will use whatever means possible to exterminate a toad. Drivers use them as target practice in the road. Kids use them as cricket balls for sporting events. Humane ethicists advise either freezing or drowning the toads as the most humane method of dispatching the pests. I too, was taught by the Australians to combat the spread of the toads by any means possible. As a backpacker lacking any real resources for the job, I was told to use my most powerful weapon—namely, my boots. I was taught to bluntly kick around the cane toads until they stopped dead.

As an ecologist, I felt that I had to fulfill my duty to an already ravaged ecosystem. And the cane toads were not hard to find. I stayed in many places in Queensland and northern New South Wales where cane toads covered the ground like a plague. Knowing about their negative ecological impact, I was ready to do something about it. At one roadside campsite near a creek and some slickrock, I encountered an abundance of the bedeviled toads. I singled one out. I picked it up by its warty back. Having no predators and no defenses other than their poison, the cane toad made no effort to resist. It didn’t even seem perturbed by being picked up. Holding the toad in my hand, I prepared for what was about to come. I let go of the toad and drop kicked it. The toad went flying onto the slickrock. I made my way to the toad. Dazed, but alive, I found it again. I had already committed to the extermination of this particular toad; it would be cowardly to back out now. Thinking thusly, I repeated the entire process a few more times. With each drop kick I imparted, I knew I was doing damage to the toad. Yet after every kick the toad still groggily got itself back up. I could still tell that the toad was every bit as alive as I was. My efforts at eradicating it simply weren’t enough. The toad wouldn’t be dispatched easily. From the outside, my toad looked every bit a toad as it did before my encounter. But on the inside, I knew, I must have done some damage. I knew I needed to end the suffering promptly and just kill the toad quickly. But I just couldn’t bring myself to the point of squashing down on the toad with my boot against the rock. I was appalled at the thought of the blood and the gore of it all. So instead I did the cowardly thing. I left the toad where I found it, hoping that it would soon die of its injuries. It seemed probable that the toad would have died soon after, but I’ll never know for certain. At any rate, my actions would not have produced anything akin to a quick, painless death. And now, I had to live with being the cause of that death. Though my hatred of cane toads caused me to maim one of their own, it could not overcome my desire to not take a life; all my beliefs about ecological integrity could not manage to win over my sentiments and cause me to end the toad’s life once and for all.

It is still possible that the cane toad I kicked around lived on. If so, the toad lived but it was the ecosystem that suffered because of it. Each cane toad, each gypsy moth that continues to live on in a place outside its native ecosystem continues to tip the balance of ecological resiliency. One does not see the consequences of continued ignorance towards invasive species individually. But collectively, the oak trees will suffer because of it. The native Australian fauna will suffer because of it too. The ecosystem as a whole suffers because of it. And thus, when an organism is causing undue harm as an invasive species, is it right to let it continue on and undermine the integrity of the ecosystem? I think not.

Though killing is psychologically painful, it is often necessary and justified for the sake of ecology.

For More Information:

- Cane Toads: An Unnatural History

- And the best scene from the film…

- And the sequel…Cane Toads: The Conquest

The Sands of Time and Change

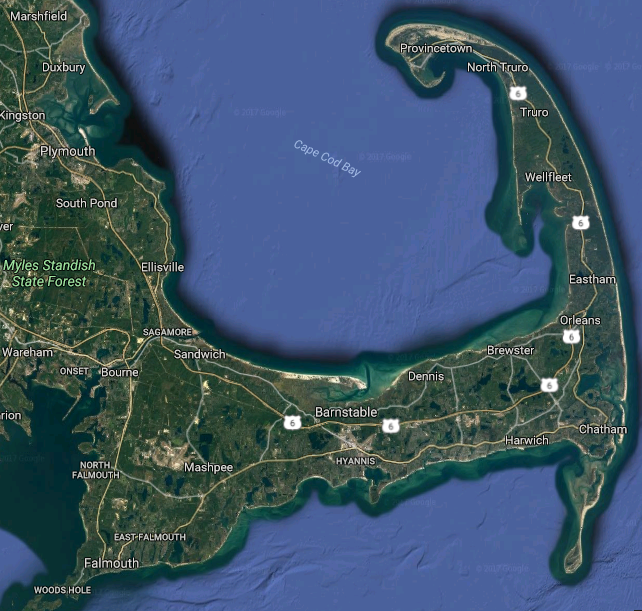

Some 50,000 to 70,000 years ago, a giant lobe of the continental glacier that stretched across North America during the last ice age ground to a halt during what is known as the Wisconsin Stage, the most recent phase of the last global glaciation. For thousands of years, that small piece of the vast expanse of ice stayed relatively stagnant at its location, neither advancing nor retreating remarkably. Though the terminus of the glacier remained more or less in place, the ice itself continually moved, acting like a giant conveyor belt carrying a load of rocks and sediment scraped from the bedrock of continental North America. Year after year the glacier persisted, bringing layer upon layer of sediment with it. About 12,000 years ago, the planet began to warm dramatically; it was the end of the last ice age. The glacial lobe, melting in the rising global temperatures, retreated north to the arctic where snow persists year round. In its wake was left evidence of the glacier’s presence; on the expansive coastal plain just off the mainland of modern-day Massachusetts was a very conspicuous mound of sediment. That pile of debris, known as a terminal glacial moraine, was the genesis of Cape Cod.

At its start, Cape Cod was little more remarkable than a hilly mound of debris pocked with depressions rising above a broad plain, for off the coast of New England the continental shelf is wide and gradually slopes down to the sea. At the end of the last ice age, with much of the world’s water being locked up in the melting glaciers, the ocean water was much lower than it is presently. For thousands of years after the glacier’s retreat, Cape Cod as we know it was not surrounded by water; it was surrounded by land. Gradually, as the Atlantic began to rise from glacial meltwater, the mound of sand and rocks finally became a peninsula about 3,500 years ago; a very primitive Cape Cod could now be identified by its shoreline. But it was not yet the Cape Cod we know today. It would still take thousands of years more to mold the landscape into its present form.

But even the Cape Cod of today was not the Cape Cod of yesterday, and will not be the Cape Cod of tomorrow. Geologic forces act with gusto on this geologic infant. All around the coast of the Cape is a blanket of sand—the telltale sign of active erosion. Sand moves quite readily in the wind and waves; there is nothing quite so solid about the Cape, no feature quite so permanent. Though formed of sand and rock, the Cape is little more than a giant sand castle in the midst of an angry Atlantic. To find a solid foundation—bedrock—one must burrow hundreds to thousands of feet down. With no solid foundation, the Cape exists in a state of flux. Just twelve thousand years after its creation, the Cape is dramatically different than the day the glaciers retreated. Cape Cod has never found its state of geological stasis.

Conspicuously ringed by a rim of white, the sandy erodible shores of Cape Cod are visible even from space.

Incessantly, wind and water work their relentless magic on the Cape, continually transforming the landscape. Though everywhere on the Cape has potential for rapid erosion, nowhere is this process more apparent than on the Eastern seaboard. Unprotected from the vast fury of the Atlantic, the eastern shore faces the brunt of its unmitigated ocean waves. The force of winds and waves cumulatively wash away the beaches lining the shore, which undermines the land above from the base. As more beach disappears into the water, land from above will tumble down to replenish the beach sands. Thousands of years of water undercutting the land have resulted in the wall of characteristic oceanside sand cliffs that line the eastern shore, and the continuously lapping ocean waves have eroded Cape Cod’s initially irregular eastern shore smooth into a long, continuous beach. Taking a look towards the cliffs above reliably reveals how high the land once sat.

On the eastern shore of Cape Cod, the powerful Atlantic Ocean gradually eats away at the edge of the Cape, forming a long continuous beach lined by sand cliffs (@ Nauset Beach).

On its eastern shore, Cape Cod loses about three feet of land every year. At its narrowest point just south of Wellfleet, little more than a mile of land separates Cape Cod Bay from the Atlantic. Given the current rate of erosion, the outermost peninsula of Cape Cod will become an island separated from the mainland in less than two millennia. Even on the time-scale of a human life, the rate of erosion is unmistakable. Glancing up at any seaside cliff, one is likely to see the underground remains of society ghastly exposed. Drainpipes emerge from the cliffs, leading nowhere, draining nothing. Electrical cables dangle limp and useless. Large chunks of asphalt lie at the base of the cliffs, evidence of past roads and parking lots. All of this evidence points to the fact that the eastern edge of the Cape was once purposely settled with the intention of staying permanently. But not even modern development could stand up to the forces of erosion over time. Eventually, even this evidence of habitation too shall disappear.

The ghost of previous settlement becomes apparent in the seaside cliffs. Drain pipes and old wiring poke out from the cliffs above (@Nauset Beach).

Along with the sand, much of the history of Cape Cod has fallen down the cliffs and disappeared into the hungry mouth of the ocean. The first twin lighthouses at Chatham have long since tumbled into the sea; later lighthouses would be built on moveable bases to prevent a similar fate. The landing spot of the first trans-Atlantic telegraph cable connecting America to continental Europe in 1879 is no more; that spot where messages were relayed across the ocean now lies more than 300 feet out to sea. As the pursuit of land by the ocean continues, more buildings face the dilemma of either moving or falling into the ocean. Man’s few accomplishments, even as groundbreaking and historic as they may be, are ultimately fleeting and ephemeral. Nothing can stop the onslaught of the elements over time. The ocean serves as a reminder for man to keep his humility.

The view is one thing, but these houses will soon have to face destiny: move or be swallowed by the ocean. (@ LeCount Hollow Beach).

Though the eastern shore is rapidly eroding and the Cape loses about 5 to 6 acres of land every year, not all of the elements work to destroy land. Land that is lost will eventually result in land that is created. However, on Cape Cod it is a losing battle; for every acre of land lost, only ½ acre of new land will be created. The rest of the sediment vanishes into the ocean depths. Summer winds transport eroded material along the shore southwards, adding to the sand island of Monomoy off the Cape’s elbow. Strong winter Nor’easters transport most of the sediment down-cape to the curling fist at Provincetown. Here, currents slow and the transported sediments are deposited, forming the classic recurve shape of a sand spit. At the very tip of the Cape, the area known as the Province Lands has been formed very recently, an accumulation of the sandy corpse of the easternmost Cape. The Province Lands are not a glacial feature, but a geologically infantile accumulation of water-deposited sand. But even where deposition occurs, erosion is present also. Just south of Race Point, where sand from the eastern Cape is coming to rest, waves off of Cape Cod Bay move sand south around the Provincetown Harbor towards Long Point. Erosion happens on many scales—a fractal pattern of sand spits develops.

Not all of Cape Cod is disappearing: sand from the eastern shore eventually settles in places like Race Point at the northern tip of the peninsula (Race Point Lighthouse).

Where there is deposition there is also erosion: Herring Beach, just south of Race Point where a road and parking lot are irreversibly disappearing into the ocean.

Water is one factor in the continual re-shaping of Cape Cod; wind is another. Unprotected from higher surrounding landforms, Cape Cod is continually ravaged by winds whipping across the seas. Historically, the erosional effect of these winds has been tempered by a layer of vegetation growing on the sandy soil. Though the soil on Cape Cod is poor and holds very little organic matter, these fragile soils once supported great hardwood and softwood forests. Millennia after the glaciers retreated, pioneering species gradually built a thin soil in the sand; larger and lusher trees were then able to grow, a magnificent forest of large pines, oaks, and in places even the nutrient-demanding beech tree. Upon landing in the New World at the Province Lands in 1620, the Mayflower Pilgrims scouted the area and remarked on the majesty of the Cape’s forests, being “compassed about to the very sea with oaks, pines, juniper, sassafras, and other sweet wood.” Though the pilgrims moved on to settle permanently in Plymouth, more European settlers were soon to follow in the late 1600’s and early 1700’s. With rapidity the native forests of the Cape were cut down for firewood and agriculture; the thin fragile soil was exposed to the unforgiving winds. The layer of green that held down the topography of Cape Cod was removed, and the fertility of the soil lost with it. By the mid-1800’s, man’s feeble attempts to eke out a living by farming the Cape all but ended. Today the stabilizing forests are in regeneration, the scraggly pitch pines being the first to reappear where man once tilled.