Category Archives: Reflection

Seeking Darkness

.

.

In a blog post from last September, I wrote how I felt like I was ‘chasing light’ by hopping from summer in the northern hemisphere to catch another summer in New Zealand, only after doing similar hemisphere-hopping travels the year prior. Now, back in the northern hemisphere, we have recently passed the summer solstice—the day with the most light each year. For me, this marks five summer solstices in a row without experiencing a winter solstice. I, indeed, have been chasing light.

But, in my hemisphere-hopping quest for summer light, I found myself inevitably pursuing just the opposite. After experiencing so many summers in a row, I ended up, quite literally, seeking darkness. Sometimes rather desperately.

The details were that I was following along a thru-hike in New Zealand. Te Araroa—New Zealand’s longest trail—which I tramped my way along from last October through February. Peak summertime in the southern hemisphere. Long summer days filled with ample sunshine in New Zealand’s high latitudes. And I was outside camping for all of it.

In spite of this, I began to seek out the darkness like a nocturnal animal. Though backpacking and camping itself are most practically done during daylight hours, my sleep schedule shifted to be more night-oriented. I was desperately craving the dark. Always an early-bird before, I instead felt the pull to become a night owl.

My daily hiking routine was far different from most other trampers. I would lollygag and nap my way through the afternoon’s hiking route—I never felt in a rush to get anywhere—and this resulted in a delayed arrival at the campsite or hut later in the evening. Daily chores of setting up camp and cooking dinner would take me even later into the evening hours. While nearly all my hiking compatriots would be in bed sleeping before sundown, I would continue to stay awake. At the fall of nighttime, I would feel a sense of relief. Reawakened, reinvigorated by the dark, I would remain conscious. I was enlivened again. Aside from a little bit of stargazing, seeking out glowworms, or swimming with bioluminescent algae, I tended to not explore much after dark. Instead, I cocooned. I would cozy up in my tent or in the hut. I would read or journal. Or, failing that, I would just lie awake and think. My mind was becoming clear and active. It was no time for sleep.

Delayed bedtimes from my nighttime activities resulted in delayed mornings. Late nights meant later waking times, and increasingly later starts to the hiking day. My daily routine of wake-hike-camp-sleep kept creeping later and later into the day. I got into an inefficient (by thru-hiker standards) pattern of waking around 10 or 11am, leaving camp by noon or later, and arriving at the next camp just before sundown (or, in some cases, after sunset). I started setting up my camp and cooking dinner exclusively by the wane light of a headlamp. And since I never wanted to go to sleep immediately after making camp, I continued to stay awake after dinner reading and journaling by the dim glow of a red light. The spiral of becoming more nocturnal continued.

Keeping this kind of sleep schedule meant that upon waking in the morning, nearly always everyone else at the huts or campsites had already departed. I would thus be greeted by a peaceful morning of blissful solitude in a beautiful location. Upon arriving at the next hut or campsite the following evening, I found most of its occupants would already be in bed, or pretty darn near to it. A direct result was that I started talking less and less to my fellow Te Araroa trampers. I became a temporal recluse. I embraced the quietness and seclusion that night offered, and I basked in this new-found introverted time.

In essence, I think what I was craving was not the darkness itself, but something that the dark provided. Nighttime can facilitate certain events and emotions that the daytime cannot do justice. Darkness sets a certain mood and ambiance, and that was what I had been craving for so long.

Summer seasons, with their long days and ample light, play host to social gatherings and long adventurous outings in the outdoors. Summer is an externally-focused season, with an emphasis on travel, exploration, and sociality. Winter seasons, in contrast, play host to a quieter, more subdued, more introspective disposition. The darkness closes off the self to much of one’s surroundings—the world becomes more limited, and the internal self begins to take focus. The snug coziness of one’s safe protected domicile on a dark winter’s day offers a feeling of security that cannot be matched by the bright and benign summer. From this position, one can look inwards at oneself, reflect, grow, introspect.

With so many summers in a row under my belt, I think my body and soul were craving that dark introspective rest period to relax and mentally digest all my recent experiences. Leading up to Te Araroa, I had undergone many long adventurous summer days of travel, socializing and exploration—a summer guiding canoe trips in the Boundary Waters, a summer working at a research station in Antarctica, an entire summer spent leading a backpacking trip on the arctic tundra of Alaska. Then to top it all off, I started on this long endeavor of a thru-hike on New Zealand’s longest trail. All this movement and exploration simply became too much for my own desires. Instead, I was craving a more relaxed pace—just to have some time to sit and process through everything I had done while the days were long and my thirst for adventure was high.

Personally, I find myself quite cognizant and responsive to the change in seasons. I grew up in a temperate climate. The places I call home are marked by a strong seasonality from summer into winter and back again. Furthermore, I have chosen to pursue a career as a seasonal worker in the outdoor industry, where the arc of my year follows the progression of the seasons—and I am outdoors witnessing the changes for most of it. In the temperate climates I call home, there is a distinct period of rapid growth and activity, followed by a period of rest and dormancy.

The plants in the temperate landscapes where I grew up have adapted to this seasonal cycle. In fact, many cannot live well or reproduce if the hard winter cycle is broken. Buds fail to open, flowers fail to bloom, seeds fail to germinate. The changes in the plants’ metabolism are triggered by changes in light and cold—processes known as cold stratification and vernalization. As a plant connoisseur, I am in-tune with the plants around me. And similar to the plants, I need these seasonal cycles for my own healthy biology.

There was only one other time in my life where I felt acutely the lack of change in seasons. It was the first time I had ever skipped a winter, opting to spend October through April in Australia instead of in the northern hemisphere. Coming back to America the following summer, I felt like something wasn’t quite right. I felt like I had missed that vital internal reset period that feels so intrinsic to my nature.

Now, as summer has officially started and the solstice has passed, darkness will ever so slowly return to the northern hemisphere. This time, I am staying put in the north for the foreseeable future. Darkness, and all it brings, will finally come to me. No longer will I have to stay up so late desperately seeking darkness. I will finally get the strong seasonal reset period that my body and mind have been craving. It may be the height of summer now, but I’m already looking forward to winter.

Chasing Light

It seems I’ve been chasing light lately. First an Austral Summer below the Antarctic Circle. Then a Boreal summer above the Arctic circle. In a few day’s time, shortly after the autumnal equinox has ushered in fall to the northern hemisphere, I will board a plane and fly back to the southern hemisphere for the start of spring. I seem to have become a season hopper.

With three summers in a row without a winter season in between, you’d be forgiven if you thought I was chasing warmth and sunshine instead of chasing daylight. Though astronomically speaking, the seasons have been summer, traditional ‘summer’ weather has been neither what I was seeking or have experienced. Last December I spent the solstice in Antarctica, though even the peak of summer there felt climactically akin to my brethren at home in the Midwest. This June, I was in northern Alaska for the solstice. Yes, temperatures could rise and be unbearable under the full, circling, blazing sun—but it could also become cloudy and reach temperatures within the range of snowfall. Indeed, though the daylight has indicated summertime, these summer seasons haven’t always seemed particularly ‘summery.’

And here I go again, back to New Zealand, back to the southern hemisphere, and back into another summer season. It wasn’t by design that this happened—circumstances and the development of life decisions just produced this unintended result. While working in Antarctica last October through February, I met someone who convinced me to join her on a thru-hike on New Zealand’s Te Araroa trail. So, while the days are short and the snow falls in the northern hemisphere, I will be on the other side of the globe chasing the warmth and summer season as we hike the island together. As we follow the trail from north to south, we will be reaching higher and higher latitudes where in summer the days become longer and the nights are short.

In the temperate mid-latitudes where New Zealand lies, the distinction between periods of night and day are pronounced, but not extreme. But life, as well as the landscape, reaches towards the extreme the more one goes poleward. And beyond the Arctic and Antarctic circles, the land goes from 24-hour sunlight in the summer to 24-hour darkness in the winter. The polar regions are places of extreme seasonal differences. The summer season knows not the winter season, and the transition between the two is abrupt with only truncated springs and falls. From the sun circling overhead continually in the summer, there is only a short transition until the suns sets and never peaks above the horizon in winter.

I have seen firsthand the way the sun wanders aimlessly around the polar summer sky, circumambulating. At McMurdo Station, Antarctica, 77.5 degrees south, I spent 118 days without a sunset. When it finally did occur, the first sunset of the fall was a momentous occasion. The residents of McMurdo piled outside to watch as their faithful sun companion dipped briefly below the horizon, only to rise less than an hour later. And though the sun had officially set, it was far from night, and would be for quite some time. In the beginning of fall, the sun stays so close to the horizon that it remains civil twilight for hours after sunset. Not until a month and a half after the first sunset of the fall does McMurdo experience its first true minutes of night.

With traditional distinctions between day and night becoming muddled at the poles, day and night become somewhat irrelevant. How is one to tell the passage of time when one cannot tell when one day slips into the next? In summer, the sky remains constantly lit. Day rolled into night, but the night seemed just like the day.

In Antarctica, during the summer season, I ended up working the night shift at McMurdo Station. Though the 24-hour clock that the research station ran on considered the shift to be ‘nighttime’, there was no darkness. The only indicator of night was that the throngs of researchers and science support staff hanging out in the galley would slowly subside; there would be a few hours of peaceful quiet while the station slept, until folks began to roll into the galley for coffee and breakfast at the start of another workday. Meanwhile, in those quiet hours in the wee of the morning, the sun was at its lowest angle on the horizon, sending in radiant beams of light through the bank of galley windows—a middle of the night golden hour.

I had no problem adjusting to working the night shift after spending my first few weeks on station as a daytime worker—the sun was as bright as always, and I did not feel like I was sleeping away and wasting daylight as I had felt when I worked overnights for big-box retail. Inside my windowless McMurdo dorm room, the lights were always off. When I needed nighttime, I could retreat to my room and sleep soundly out of the sun. But were I to choose to go out and play instead, the sunlight would be my constant companion.

I had more experience living under the midnight sun this summer, as I led a 50-day backpacking trip north of the Arctic Circle to Alaska’s Arctic National Wildlife Refuge. Our latitude was not quite as high as McMurdo—only at 69 degrees latitude—thus the extremes of sunlight were not as pronounced. But what this trip to Alaska lacked in sheer latitude, it made up for in intensity of experience. Gone were the modern conveniences of McMurdo Station. There was no longer any indoors to hide in, no eternally dark dorm room or dimly-lit dark bar to retreat to. Instead, we were out in the backcountry with no more than we could carry upon our backs. Our only shelter was a thin-walled tent, and the daylight filtered right in. We either made friends with our eyemasks, or we learned to sleep in the light. Once again, the time of day became irrelevant—there was no hiding from the constant presence of the sun.

It took a number of days before I lost the nagging feeling that comes after looking at the late hour on my watch and feeling the pressure to get a hustle on to make camp before darkness falls. Throughout the duration of the trip, I kept tabs of the time on my watch—not out of necessity, but more out of a curiosity of how our circadian rhythms were adapting. Our days slowly dragged out to be longer, as we stayed up later enjoying each other’s company and slept in longer the following mornings. Thus, we ended up being awake through the darkest hours of the day, and even towards the end of the trip after the sun had been setting below the horizon, the light remained with us. Even in the depth of night on our last day in the Wildlife Refuge, it remained light enough in the tent to read a book.

In spite of the mounting fatigue from daylight that comes with constant exposure to lightness, I appreciated the daylight as a benign and amiable companion in a remote and unfamiliar terrain. Here we were, traveling for weeks in the Arctic National Wildlife Refuge, where wolves and grizzly bears roam wild. The signs of these animals were all over—tracks, scat, kill-sites. But the daylight made the wilderness seem friendlier. All told, we saw six wolves and seven grizzly bears on the trip. Seeing the bears and watching their natural disinterested movements in the daylight provided much more psychological comfort for us than wondering if out in the darkness somewhere was a bear lurking just outside the tent.

At about the same time on the trip that I began to miss the creature comforts of home—dry feet and doorways instead of tent zippers—I also began to miss the darkness. Aside from being able to sleep better in the darkness, I began to miss darkness not for darkness itself, but for what it brings to us. The constant daylight drowns out the stars all polar summer long. I’m constantly reminded that people forget this, as I am asked quite often if I saw great stars or aurora. Unfortunately, I was able to see neither stars nor aurora, much to the disappointment of my star-gazing self. And too, having the darkness creep in at the end of the day provides a natural daily cycle of gathering in your shelter for rest. Darkness too, lends itself to gathering around a campfire for light and warmth. Though we did have a campfire on the riverbank one night in Alaska, the magic of the fire just wasn’t the same in the light hours.

As much as I began to miss the darkness, when it finally did come, it felt uncomfortable and foreign. Towards the end of our trip, the nights had been gradually growing dimmer. But right after leaving the Wildlife Refuge, we caught a shuttle ride to Fairbanks, which sits below the Arctic Circle. Darkness descended upon us as we camped in Fairbanks that night. For the first time in nearly two months, it was no longer light enough outside to walk around without a headlamp. The feeling was unfamiliar. Suddenly all the scary feelings of darkness came rushing back in that gut-wrenching primordial fear of the unknown. My how easy it is to forget what darkness is like!

This coming summer, the distinction between day and night will not be as pronounced as I hike the Te Araroa as it was when I spent time closer to the poles. The mid-latitudes will provide a kinder balance of light and darkness each day. Nevertheless, as fall and winter begin to descend on the northern hemisphere, I will once again be off chasing light.

State of Mind, State of Being

space

The United States of America, with its fifty nifty geographical sub-units, neatly divides up this diverse nation into different states that each has a generalized culture and personality. As someone who is not yet settled down with a permanent address, I still have the flexibility and open-endedness to decide which state I want to live in for the long haul. From working jobs in a variety of locations, I have gotten a taste of many different geographies, a smörgåsbord of potential places to call home. In any given year, I seem to work in about three different states, which doesn’t usually include my birth state of Michigan. This prolonged period of ‘geographical investigation’ has given me some insights into where I might want to settle permanently based on my experiences in each state. While I have explored around the country quite a bit (see this page on my personal website for the most up-to-date map of U.S. counties I’ve been to), I’m a northerner at heart—I’ve never stayed long in a place under 40°N. And while I’ve worked jobs on both the East and West Coasts, I always return home to the Midwest.

From my adventures, I have my own thoughts about potential locations to settle, as well as to what my ‘soul state’ might be. But I thought I’d elicit some help from the omniscient ether—by taking a number of sleazy internet quizzes to see where the quiz writers think I belong. These quizzes—though far from scientific—are quite fun to play around with. I’ve listed them here according to my self-rated quality of the quiz, from best to worst:

What were my results? Out of seven quizzes taken, surprisingly none of them yielded the same state. However, there seems to be a strong connection to northern New England, as I was matched with Maine, New Hampshire, and Vermont (even though New York is not considered part of New England proper, I’ll clump it in with this category because the most desirable part of New York for me, Upstate, has a lot in common with northern New England). These four states—charming small towns, more rural populations, historic places, and winding roads through hills and deciduous forests—all seem to be a good match for what I’d be looking for in a habitat. The quiz from Quizony was the only one that picked what I consider to be my ‘soul state’ of Vermont: fiercely-independent, sustainability-minded, ample greenery, and the fewest Wal-Marts of any state.

space

space

space

space

space

And as for my natal Midwest? Sadly, no quiz matched me with my birth state of Michigan. I guess it turns out that I don’t fit in with the bulk of the state, though I think quite highly of life in the rugged frozen Upper Peninsula (Yoopers are a special breed, and I don’t think I could ever live up to their cred). I was quite happy that Wisconsin appeared as a match. I really am fond of the upper Great Lakes region, especially around Lake Superior, and I’ve been quite frequently perusing for real estate in northern Wisconsin. Cheese curds and a good football team? Count me in.

space

space

Then there were two far-flung results. Washington State, with its forests, mountains, and avid outdoor recreation culture seems to be a good fit for me. And though I enjoy visiting and recreating in the west, the West Coast has never really felt like home to me. Finally, my most out-there match was with Tennessee, provided by Buzzfeed. Apparently the quiz determined that I have an undiscovered penchant for country music that makes me belong in the South (even though when given the quiz question for musical preference, I explicitly chose rock over country).

space

space

space

Of course, no online quiz can ever compare with the process of getting to know a state in person. So get out there and start exploring to find your own perfect state!

space

space

space

Flirting with a Smartphone

spacespacespace

My close friends may know that for a millennial, I am quite a technological holdout. I still use Microsoft Word 2003, listen to music on a 4th-gen iPod Nano, and have yet to use social media platforms like Snapchat or TikTok. But what probably most makes me a Luddite is that I still have not acquiesced to the smartphone.

For the second time in my life though, my reliable brick of an ‘unsmart’ flip-phone is becoming obsolete long before it quits working. Network upgrades to 5G will soon render my 3G flip-phone incompatible.

And recently, I was loaned a smartphone to use while on a temporary job assignment, a phone which I was allowed to keep after the job was finished.

Am I now at a crossroads where I’ll join the darkside and become a smartphone user?

I must admit, having a smartphone has been fun for these first few weeks (although I refer to it as a ‘phone,’ it does not actually have a SIM card and therefore cannot be used to make phone calls, which is the primary definition of something being a ‘phone.’ I have been trying to call it for what it actually is, a ‘pocket computer,’ but the name hasn’t stuck and most people would colloquially recognize it as a phone anyway.)

Whereas in my primitive pre-smart-technological life, I would keep either a mental or written list of things I wanted to look up on the internet, and then wait to boot up my clunky old second-hand computer (c.2015) and do a big internet search session, now with a smartphone I have instant access to the world wide web and instant gratification to search for any bizarre or random thing that pops into my head at a moment’s notice. Having the internet in my pocket makes me realize how often I think of random questions that I’d like to research, and also how often I forget about those curiosities if I don’t immediately look them up.

Adamantly decrying smartphones for so long as I have, I found it funny how quickly I became attached to that little pocket computer companion once it was at my fingertips. Oh how easy it was to check messages and emails, to stay in constant contact with the broader world! I kept a web browser pulled up with my email on the smartphone. On breaks or brief moments of down time I could just so easily check for any new messages. And I constantly did check. Of course this was silly—my life hadn’t changed any—previously, checking my email and other messages every couple of days had been sufficient. And it still was sufficient. But I felt that tug of compulsion to constantly check and be connected just because it was so easy. The FOMO was real and it was strong—I couldn’t stand the possibility of missing something, even if it was just the latest promotional email from a company I bought one thing from years ago.

And then, there was my downtime. That phone was so easily a time filler. Getting off work, I would sit and relax in a big comfy chair, phone by my side. Inevitably I’d start browsing. My favorite site was realator.com. Before I knew it, a couple hours would have passed and I’d have progressed into looking at the real estate market in several far-flung cities that I had no intention of ever living in. Wikipedia rabbit holes were also another vice of mine, one that also got me lost for hours. On those evenings alone, that smartphone proved to be a source of mindless recreation, addictive from all the endorphin hits upon each new stimulus viewed. But it also was a huge time-suck.

After leaving the job that necessitated the smartphone, I lost my access to 24/7 high-speed internet along with the SIM card. My next job had me relocating to Bend, Oregon, and while on the extended cross-country drive, it was tough to give up that instant gratification. No more could I instantly research whatever popped into my mind, say the real estate market in Rockford, Illinois, or learning about what had actually happened at the OK corral. On the drive, I found myself periodically checking the phone like I had grown accustomed to—a habit that was so quick and mindless to form. But without service, the smartphone was little more than a slim computer. I had a lot of time to ponder things on my 2,000 mile drive, but I knew that I could no longer just whip out the phone and look something up. Still, the urge to research things on the phone was strong. Irresistible even. I often found the desire compelling enough that sometimes I just had to curb the anxiety by pulling into a McDonalds parking lot to bum WIFI for a few minutes.

So, after my month-long flirtation with a smartphone, am I ready to make the transition from a flip-phone myself?

Absolutely not. I appreciate my flip phone for what it is, and for what it is not. It is just a phone. It is a utilitarian tool, used to call people. The smartphone, though sleek and beautiful and convenient and powerful, is too much for me to handle. I realize I cannot control myself when with a smartphone. I do not want to be counted among the masses who mindlessly check their phone out of habit at every microcosm of an empty microsecond. I like to be free to be alone with my own thoughts. I do not wish to feel so connected and dependent on a technological device that I cannot bear to have it not by my side.

Some folks make the argument that technology is not the culprit, but rather phone abuse is from a lack of self-control. Phooey. This technology is made to be addicting. Even with my staunch anti-smartphone values and austere self-discipline, I still found myself getting sucked into the mire of addiction. Best to just cut it off and not have the temptation.

In the end, though I have decided to keep the smartphone, I have decided not to get a service plan for it. I will use it only like I use a computer—occasionally and with an intended purpose. And though it is becoming more difficult, I can still operate in a world that is becoming increasingly interconnected and dependent on smart technology. More than anything else, I value the freedom of not being connected all the time. Though the perks of a smartphone are charming, it is not worth the cost to me.

Space

Space

Space

What I Learned from 23andMe

It all started innocently enough the last time I was with my sister. We were talking about how different we are, and I invoked the old teasing trope that my sister Allison was switched at birth (though there is anecdotal evidence, nothing has been scientifically proven at this point). As we were talking, it clicked in my mind that maybe we should take a DNA test to solve the matter. In recent years, at-home ancestry DNA test kits, like 23andMe and Ancestry.com have become quite popular and affordable. I proposed to Allison that we could find out definitively once and for all if indeed we were siblings or not; I would take a test if she would take a test. I have since gotten my test results back, but as of this writing, Allison still has not yet even sent her test in. I’m taking this as a sign that Allison knows the truth and is still trying to hide it…

Aside from settling the matter as to whether my sister and I are actually blood-related, I was mostly curious where the bulk of my DNA comes from. Growing up in America, especially in white populations, we often like to talk about where our ancestors migrated from, whether we definitively know where or not. White people will list off a smattering of European nations, proud of their heritage as a European mutt in this country we refer to as the American Melting Pot. I grew up, however, in a fairly homogenous town, the aptly named Holland, Michigan area where most everyone is to some extent Dutch. It’s no surprise, then, that I considered myself Dutch, and not much else. If you ain’t Dutch, you ain’t much! But aside from growing up in a town with windmills, wooden shoes, and an annual Tulip Festival, there wasn’t a lot of evidence to say how Dutch I actually was—or if I had any other surprises in my genes. Sure, I had a pair of Great-Grandparents who emigrated from the Netherlands, but other than that, my not-so-distant relatives were American-born. My family has a few historical records that show when a small number of distant ancestors migrated, but other than that, it was just generally assumed that my forebears came from the Netherlands. Or northern Germany, as they are geographical neighbors. But the Germans never really got more than a passing mention in my family’s lore.

Upon recommendation from a friend, I decided to go for the 23andMe test kit. The test kit breaks down recent ancestry into a multitude of regions and sub-regions, as well as giving genetic information on phenotypic traits and health risks with a provided scientific backing behind it all. Once I received the at-home test kit, I spit a copious amount into a tube and then mailed the sample away to a lab to await my results. I mostly wanted the results to show how ‘Dutch’ I actually am. Or, if in fact my DNA would have a surprising trace of genes from another ethnicity. Some Euro-American individuals, in an effort to bolster their feeling of diversity, may talk about how one of their distant ancestors was a Native American or an enslaved African-American. There was no such talk of this in my family though. Would the DNA test reveal otherwise?

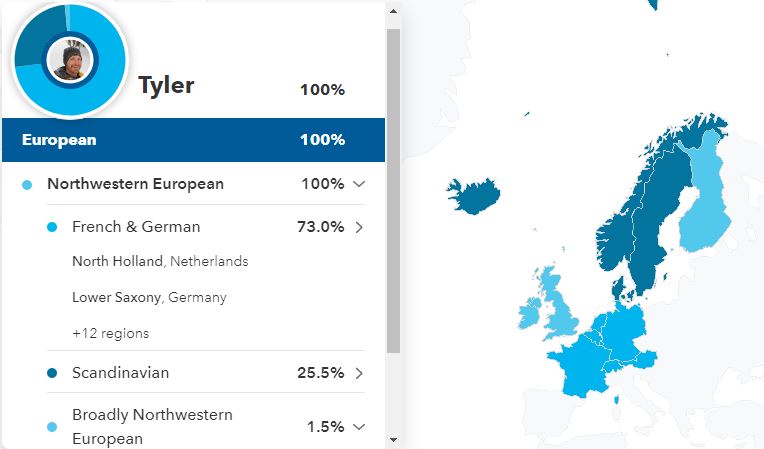

After getting my results back, it turns out I am indeed very white—or more appropriately, of European genetic origin. 100%, in fact. All of my genes come from European heritage (it should be noted that 23andMe types DNA according to particular genetic sequences which are held in common by a reference population with known ancestry to a particular region. These results mean that I share particular DNA segments with people of a known regional European ancestry).

space

space

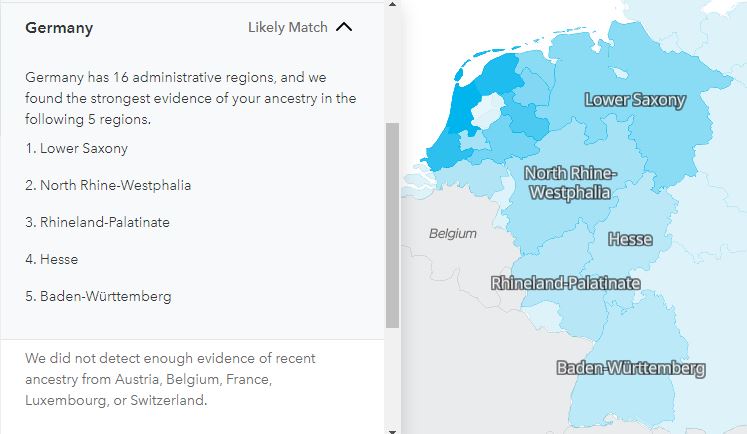

Not surprisingly, as the story told by my living ancestors attests, the bulk of my DNA originates from the Netherlands. 73% match in fact for the category 23andMe titles ‘French and German.’ Within this grouping of countries, 23andMe does not break down ancestry by percentages; instead, ancestry DNA matching is listed by likelihood of a DNA match. Turns out, I’m a ‘highly likely’ match for the Netherlands. This is followed by a ‘likely’ match for Germany. All other countries in the region—Austria, Belgium, France, Luxembourg, and Switzerland—I did not have any likely DNA matches from. Looking at my results, I am mostly Dutch ancestry, as I believed, with the smattering of Germans that my family only slightly acknowledges.

space

space

The biggest scandal of the DNA test, the big surprise that I had been waiting for, was that I am 25.5% Scandinavian ancestry. No one in my family had ever mentioned anything about Scandinavian ancestors! To think that my family has been hiding the fact that somewhere far back in the family tree are a few crazy Swedes or Norwegians! (Given this new information, it now all becomes clear why I fit in so well with the primarily Scandinavian ethnic population of northern Minnesota. Uff-da!)

space

space

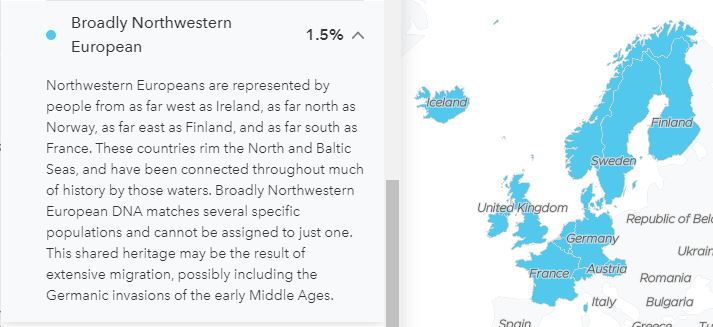

To round things out, the last remaining 1.5% of my DNA is defined as Broadly Northwestern European. These are genes that are common in Northwestern Europe, but not specific to a particular country. To sum it up, I suppose, I am of broadly Northwestern European ancestry. No big surprises in my genes, I’m afraid.

space

space

Reflecting on what I learned, I can’t say that my life was changed too much by finding out my DNA ancestry. It pretty much confirmed what I had already known, or had at least suspected. Before any person takes the test, though, 23andMe does go through a fair number of disclaimers aimed at educating participants in how learning the results of one’s DNA makeup can be upsetting. I am not upset, though. If anything, getting my results makes me even more likely to pursue a long bicycle tour of Northwestern Europe. But I was planning on dong that someday anyway.

Aside from just learning the background of your ancestral DNA, 23andMe offers an outlook into certain genetic traits and health markers. Many of these of course are for disease risk and are quite serious to look at. But there is also the much lighter side of genetic traits, which range from the standard to the inconceivable.

Some of these traits seem intuitive that there is a strong genetic component. For example, 23andMe correctly predicted most of my phenotypic features—blue eyes, unattached earlobes, little to no back hair, an uncleft chin, and no dimples. In regards to hair loss, much to my relief, I have an 82% chance of not going bald before age 40 and an 87% chance of not having a bald spot.

And then the genetic results get more bizarre and interesting, as the trait report begins to list not just physical traits, but also behavioral traits and preferences. These more far-flung personal attributes do have certain genetic markers in common among populations with said trait, as per 23andMe’s research, though the company also acknowledges other physical and cultural factors are at play too. For example, I have about average odds of hating chewing sounds and I am about as likely to get bitten by mosquitoes as others. But, fortunately I’m less likely to be afraid of heights, and also less likely to be afraid of public speaking (I can attest to both). Apparently, according to 23andMe, my circadian rhythm should wake me up naturally at 8:16 AM. I also have less than two percent Neanderthal DNA.

Aside from that, 23andMe says that I’m more likely to detect a distinct odor in my urine after eating asparagus (that’s true…), but also that I’m more likely to think cilantro tastes like soap (I don’t). And apparently I don’t have a particular preference for either chocolate or vanilla ice cream. I’ll actually eat any ice cream. And on that note, I’ll say thank you to my Northern European ancestry which has blessed me with an incredibly high dairy tolerance.

space

space

space

Can a Collector Live in a Tiny House?

space

I found a rock the other day. A shiny metallic piece of schist about the size of a travel bar of soap. It’s a beautiful specimen of its own accord, found as part of the mélange of rocks jumbled up in Alaska’s glacially-formed landscape. I decided to keep the rock as a small souvenir, a tactile memento of my first winter spent in interior Alaska. Amateur geologist that I am, I thought the schist would make an excellent addition to my rock and mineral collection.

You see, I am a collector. My rock collection is testament to this. Boxes and boxes of rocks I have picked up from places I have visited now sit begrudgingly in my parents’ basement. The finest specimens I keep on display in a little nook in their basement workroom, but without a permanent space yet to call my own, most of my treasures still wait in expectation for when they will once again see the light of day.

The rocks I collect are not only intrinsically beautiful, but they all have added meaning for where I was when I collected them. I am a collector—of things, yes, but also of experiences. Working as a dog musher north of the Arctic Circle is just the latest life experience I am collecting. Though I won’t need to hold the little piece of schist in my hand to remember my winter spent in Bettles, Alaska, it can serve as a conversation starter or as a token to trigger my memories of time spent here.

At the same time that I am adding to my ever-expanding rock collection, I am also living in a repurposed trailer that housed construction workers who built the trans-Alaskan pipeline. Some nights I theoretically sketch out in my head if I could imagine an entire home being placed in the 8’ by 14’ unit that makes up my apartment. Kitchen here, bathroom there, sleeping loft above. It’s an enthralling exercise, as I have a growing interest in tiny homes. Living in staff housing, as I typically do, I am accustomed to occupying smaller spaces, though none of them ever being a bona fide tiny home and none ever being a permanent residence either. Regardless, constantly moving into and out of staff housing for the past number of years has given me great practice in small living, as well as showing me how simple it can be to live out of a couple duffel bags in a small space for an extended period of time.

But sometimes I have to wonder to myself: can a collector of things live in a tiny house?

space

space

It seems like my desire for tiny house living might be at odds with my natural inclination as a collector. The tiny house philosophy, after all, is about living a life with fewer things in general. To live in a small space, you have to cut out what is non-essential. I’m afraid it may be that my rock collection, though exceedingly cherished, is fairly non-essential to my everyday life.

And yet though I contemplate tiny house living more and more, the older I get the more things I accumulate, and the more reluctant I am to dispose of the things which I have acquired. Though I believe myself to be in one of the lowest percentiles for possessions owned by a 30 year-old American, my various hobbies have resulted in quite a collection of things. In addition to my rock collection, I now own a wide assortment of backpacking and camping gear, snowshoes, cross-country skis, a canoe, and two bicycles. And that’s not to mention other things like the massive volumes of books that I have accumulated. If push came to shove, I believe, I could still fairly readily pack all my essentials into my hatchback with my canoe and bicycles strapped on the outside. As for now though, with ample storage space at my parents’ place, I don’t yet have to make the decision between being a collector and living in a tiny house.

But if I do at some point opt to try the tiny house lifestyle, it might come to the point where I must make the choice between having more things and living simply in a tiny home. As that potential day is still far down the road, I can only speculate what the outcome might be. Perhaps in ten years, my collection of rocks won’t seem as important to me as it does today. Perhaps I’ll somehow incorporate my rock collection into the build of my tiny house. Maybe I will still be a limited collector of things. Or maybe I’ll have to switch to just being a collector of life experiences instead.

Only time and future experience will tell if being a collector of things can be compatible with living in a tiny house. In the meantime, I’ll continue practicing the tiny house ethic of being mindfully intentional with the items I do decide to keep. Each item I decide to hold onto must serve some practical purpose or be imbued with some sort of special significance. With that in mind, I will be very intentional about the one souvenir rock I will ultimately bring home to my collection from Alaska.

Nature’s First Green is Gold

Forest Path in Spring with Bright Green Trees (c) Matthias Hauser

It was an inconsequential day, about ten years ago now. A fresh, bright, day in May; the sun shining kindly and the air full of perceptible warmth for the first time since winter.

Spring fever had struck. We were a group of high school seniors, expectantly awaiting the impending days of graduation, summer freedom, and the privileges of adulthood. Academics, that lynchpin of education, were no longer the most important thing on our minds. Conversations instead turned to commencement and the life beyond. Mrs. Aupperlee’s 4th Hour AP English class reflected this sentiment: though it had been a particularly social class all year, the excitement of spring days had amplified its gregariousness.

We enter the classroom early, each filing into his or her own chosen seat to commence the pre-class banter. Fourth Hour was the last obstacle before lunch. Attention spans would wane, and the classroom atmosphere would become casual. Typically we would have to edit essays or practice for the upcoming AP exam, but our class knew what subjects to broach to get Mrs. Aupperlee off on a class-long tangent about things little related to English literature.

Today was just going to be another ordinary school day to get through, once again.

The bell rings and Mrs. Aupperlee takes attendance. Unexpectedly, she announces that everyone should get out of their seats and follow her. Today we would be going outside. We follow, through the double glass doors, out onto the lawn that surrounds the school. Mrs. Aupperlee continues on, in the bright May sunlight, to the very edge of the lawn. She pauses at a tree which, until now, none of us had ever given particular attention. Standing still to draw us in, she produces a piece of paper and proceeds to read: Nature’s first green is gold,/Her hardest hue to hold…

We listen to the poem as we stand outside. The tree’s freshly budded leaves wave golden in the light breeze. Some of us notice this, as the verses of poetry glance past our ears and the wind tussles our hair. Yet, standing there, some of us also wonder inaudibly why we came out here today. The poem was simple enough. Was the arboreal visual necessary to understand Robert Frost’s words? Isn’t it more expedient to just read poetry indoors? And who even really cares about looking at trees anyways? Our English class, to this point, had only been taught in a classroom. And besides, what even did Robert Frost have to do with our curriculum at the moment? Personal erudition, as lofty as it may be to high-minded intellectuals, has little to do with the forthcoming world of AP Essays and standardized tests. Why were we spending our class time this way?

As that high-schooler, I can’t recall exactly what I was thinking in that specific moment. Being the ambitious, productivity-minded student that I was then, I was likely questioning the value of walking around outside during class period. I had enrolled in this course, after all, primarily because it was an additional AP credit, and not from an inherent love of literature or poetry. English was one of those necessary evils of high-school education, one I had long endured with much chagrin. My future, too, was headed in a different direction; I had been accepted into an engineering program in college already. I expected AP Literature to be my final English class and that I would leave writing behind altogether. I saw little need then for the frivolities of poetry.

And now here I am ten years later. Though the particular details of what I thought on that late May morning have distinctly vanished from memory, our class’s spontaneous visit to the budding tree, along with the poem we shared, still remains clear. In retrospect, all the other things that I thought relevant and important ten years ago—homework assignments, AP test scores—are now antiquated and defunct memories. What remains with me now is the fact that we did go outside and that we did read a poem while crowding a tree. That single small classroom exercise, though it lasted just a few trivial minutes in duration, was influential enough to hold fast in my memory even a decade later.

From time to time, I find myself pulling out that memory, particularly when the first leaves of spring emerge. Without much conscious thought, I’ll suddenly be quoting Robert Frost, if not to my traveling companions then internally to myself: Nature’s first green is gold…

In the ten years since high school, I have changed substantially from the person who I thought I was then becoming. It was small events like reading the poem by the tree that slowly molded me into the person I would become. There was no way I could have realized it at the time, since the poem had no immediate impact on me. However, the power of the poem shared by the tree would lay latent in me for years, until, slowly, it would compound with other life experiences until I realized just the direction I had been traveling in and the person those events had been shaping me to be.

In part, thanks to that high school English class, I take notice of the trees now. Whereas before trees to me were mere background scenery, common and forgettable, I now take notice of their delicate intricacies. The changing of the seasons has become vitally important to my inner well-being, and poetic works like Frost’s serve as reminders to pay attention to the daily acts of beauty that are occurring all around us. I now can’t see the first leaves of spring without also thinking of Robert Frost.

In the time since high school, I have also found my niche in the work of environmental education. My primary occupational duties fall along the lines of educating and exposing individuals to the outdoor world—biological, geological, ecological. To those who I instruct, I primarily give facts and explain complicated ecological interrelationships in the most scientific sense. But more than just a rote recitation of facts, I aim to use my capacity as an educator to teach people a new, ethical perspective of how we relate to the natural world just as how we relate to each other. In my job duties, I now take individuals outdoors to different environments—to the world outside of the classroom where didactic instruction may not be as practical but the lessons learned become all the more memorable and valuable.

As I have now become an educator myself, I think back to the point that Mrs. Aupperlee was trying to impress upon us by taking her 12th grade English class outside on that May morning. More than teaching us facts about grammar or even exposing us to a new poet, I now believe that Mrs. Aupperlee was teaching us something of higher accord. She was trying to affect our ethical bearings, educating us to be observant, to notice things, to be citizens of the world. Inevitably, facts fade. But who we are remains. That day, on the lawn surrounding the tree, ours was not a factual lesson in 20th century American poets or even in tree biology. It was a core lesson in paying attention. It was a practice that told us, as young people, that indeed we should be able to notice the significance of the world around us, and that indeed we can stop and reflect in its beauty and be all the richer for it. It was a lesson in how we need poetry in our lives. In my capacity now as an environmental educator, this is the ethos which I try to cultivate in my students. This is not part of an education of facts and figures, but of a higher order of education, an education for citizenship.

Ten years later, I still remember that day in Mrs. Auperlee’s English class. It’s testament that a single lesson, no matter how small, can leave a lasting impact.

Nothing Gold Can Stay

Robert Frost

Nature’s first green is gold,

Her hardest hue to hold.

Her early leaf’s a flower;

But only so an hour.

Then leaf subsides to leaf.

So Eden sank to grief,

So dawn goes down to day.

Nothing gold can stay.

ha ha

To Know a River

Can one get to know a river, like one can get to know a person?

Does a river have a personality? Can it have moods?

Can one get to know for themselves the breadths and depths of the unfamiliar waters, as in the breadth and depths of another person’s soul?

I set out on my canoe expedition to know the Green River. To experience the river as a living, moving force. I wanted to see if I could truly get to know a river.

I set out to make the Green my river, the one river that I would know and esteem. I desired to create a personal history with the river. I would know her by floating through her waters.

It was nothing short of a relationship. We started small, in the headwaters. I introduced myself. I had come there to court her. I moved slowly, methodically at first. Upriver, she only revealed the most shallow parts of herself, a superficiality. It was a slow start. I had to prove that I had the will to endure; the stamina to weather the rocky growing pains of a fledgling relationship. The days passed and the miles progressed. Our relationship grew, and I became more familiarly acquainted with her waters.

Further down the river, I became increasingly taken by her course. I had seen more of her history. I was beginning to understand more of her trajectory. I began to get comfortable with her. My course and her course were entwined, for a time, together. I began to build trust and reliance on my ceaselessly moving river companion.

Over time, I had seen our relationship grow and change. I knew more of her history. I saw so much of her that a happenstance observer would never see. I felt an intimate connection.

But did I really know the Green River?

I had been with her on days both fair and foul. I had seen her in moods calm and sedated, as well as enraged in a storm. We had spent long nights together, and early mornings before sunrise. I saw the tributaries that influenced her character. I had even been immersed in her very substance.

But all that I had learned, was not, and could never be, the entirety of the river.

For the Green is not just one river. It is many rivers, all intricately woven together in a single flowage. The Green will, as it has for eons, continue its life through the seasons. Gradually, inevitably, through the imperceptible slippage of time and the perpetual cycling of the seasons, the Green will slowly shift into another river altogether. And, just as the largest storms in life can shake a person’s character to their core, so can an abrupt tempest drastically change the character of the river. The Green is not stagnant. It is eternally growing and changing. It is a diversity of rivers that is known by one name.

Like so many human relationships, mine with the Green River ended. We parted ways, amiably, I would say. I couldn’t court her forever. I had to move on to other things. Unperturbed by my absence, the Green kept flowing about her course. And all I was left with were the memories of our brief courtship, docile at times, tumultuous at others. Though I had learned so much about her, I knew I could never fully understand her.

This one river—known commonly as the Green—so many people have developed a relationship with her. So many people have a history with this river. So many people have gotten to know her depth and breadth to the extent that they can, creating their own stories with the river along the way. I count myself lucky to be among them, for even as short of a time as I could get to know her.

And in my time, I saw just a portion of her. I knew the Green only in one season of her life. I never knew all that composed her, never penetrated her depths. She is a seasoned veteran, a collector of an expansive watershed. She is much older, much wiser than me. She remains unperturbed, undaunted by her would be suitors like me. She remains timeless. An enigma.

Just as the depths of a person’s soul can never fully be understood by another, so too will a river’s waters remain an imperturbable mystery to a man.

The Green River Epilogue: The Confluence

The confluence of the Green and the Colorado Rivers. (c) Jean Clark

One-hundred-and-twenty miles downstream of the town of Green River, Utah, past steep sandstone walls and through the winding labyrinth of canyons, the Green River finally reaches its terminus. Its silt-laden waters, wearing an opaque muddy brown-green veneer, run into the deep red hues of the Colorado River. The confluence is seen by few but the intrepid; it lies tucked in a maze of canyon walls, perfectly inaccessible, save for the adventuresome boater.

The confluence of the Green and the Colorado was a goal of mine to reach on my Green River expedition. What more natural ending place than where the river itself ends? After all, I had started the journey over 700 miles upriver, where the headwaters of the mighty Green become navigable. It only seemed appropriate to paddle the river to completion.

I didn’t make it to the confluence, however. I really didn’t expect to either, given the external time constraints that crept up upon the journey as I neared its commencement. Such an ending as the confluence would have made for a tidy, complete story to summarize the trip. It would have been easiest to say to others that I had paddled the entire river. Instead, reality and necessity broke the river into sections, and I found my paddle of the Green to be finished incomplete—65 miles left unpaddled near its rocky headwaters, 57 miles unpaddled through the raging rapids of Dinosaur National Monument, and the last 132 miles of flatwater from the end of Gray Canyon to the confluence.

In retrospect, it’s far too easy to look at those 254 miles that I didn’t paddle, and to think about all of the river I had missed along those untraveled stretches. What experiences were left unknown? It’s easy to let my mind focus in on what I didn’t accomplish during my expedition than to think about all I did accomplish. Twenty-eight days on the river and 463 miles of paddling is no small feat. That’s nearly two-thirds of the navigable river itself. It’s like traveling from Chicago to Pittsburgh with all of my possessions in one 14-foot long boat.

Even though I didn’t paddle down near as much of the river as I had anticipated or had dreamed about, I was, and still am, extremely satisfied with the length and the outcome of the trip. Regardless of the ultimate distance traveled, I had accomplished so many things on the journey. I had taken the opportunity to get out into the wilds and to explore some places unknown to me via reflective self-propelled travel. I had spent nights out in the backcountry alone and with the company of my Dad and my close friend Jon. I witnessed the gradual change in the landscape from the mountainous headwaters of the Wind River Range, through the high desert plains of Wyoming, and finally into the canyon country of Utah. I saw the brilliance of stars. I heard the call of wild animals. I had immersed myself in the instantaneous reality of the elements, testing my endurance through weather both hot and cold, parched dry or rainy, high winds, dead calm, and even a snowstorm. My mental and emotional states were tested to endure the journey just the same as my physical state was tested to endure. And I accomplished all of this in just 463 miles. I didn’t even need all 717.

Despite never making it to the confluence as a natural geographic ending for the expedition, the trip itself, in my perspective, came to its very own well-suited ending. By the end of Desolation and Gray Canyons, I had had my fill of experiences and lessons from the river, and I felt perfectly ready to end the journey. Though I did not get to see the entire river, I walked away with so much of what the river had to offer, even over the shorter course of distance traveled.

Even though I am now off the river, the very water which I paddled on still continues downstream towards the ocean. Much of it has likely passed the confluence already. It’s a way to know that my direct experience with the very substance of the river itself is intricately tied to the greater watershed. The confluence will still be there years to come, just like the rivers have been flowing there for thousands of years. Someday I hope to return to see the confluence for myself.