Dragonfly Morning

Dragonfly eating a yellow jacket. (C) Bob Armstrong

The low morning sun breaks just over the distant trees. A direct sunbeam reaches the clearing below at the water’s edge. The air buzzes with creatures aflight, fresh sunshine glinting off lacy wings. I amble around the serene morning landscape. It is late spring. It is the morning of the dragonfly.

Days ago I watched these creatures emerge from the depths. Standing ankle-deep in a shallow stream, I crouched over a sunny rock. A nymphal dragonfly, mottled and brown to blend in with streambed gravels, crawled out of its watery home to the land above the surface. Stocky and strong, the size of a quarter, the nymph is the tank of the littoral zone. For months—even for years—the dragonfly nymph has patrolled the waters of its home. A voracious predator, it will seize any prey nearby into its strong maxillae. Powerfully the nymph shoots through the running stream with a water jet through its anus. Bloodworms are common prey, mosquito larvae too. Even tadpoles and minnows cannot escape the appetite of the mighty dragonfly nymph.

As of yet the nymph has known nothing of the land above the surface. Water has been its domain since it was an egg. Yet the dragonfly nymph is drawn by the biological imperative to crawl beyond. Out of the deep they will come, en masse in spring, then steadily during the summer. Squatting down, I watch the next generation of dragonflies emerge from the deep. Sunlight glints off the nymph’s still wet body; in a matter of minutes it will dry off completely. Pausing on a flat rock, the nymph looks dead and desiccated. Still, the nymph is fully alive; it soon reanimates, crawling onward towards its destination of the high brush.

Having completed its arduous landward journey, the dragonfly nymph clutches an emergent piece of grass. From here the nymphal stage has moved its last. The exoskeleton dries out even more. The nymph has died to the watery world, becoming nothing more than a mere mummified remnant. But inside the journey continues. Slowly, a weak suture line opens up along the back of the neck. The alien within the husk starts emerging. First the back bows out. Then the head pulls free. The creature arches its back, pulling out its legs one by one. One more arch of the thorax and the creature’s long abdomen is pulled from the husk of the nymph. Bright green and soft, the newly emerged dragonfly is exposed and vulnerable. Resting on top of its former exoskeleton, the dragonfly slowly hardens. The maverick of the air expands its wings for the first time in anticipation of flight. Hours later, the dragonfly is ready. It now joins the aerial display of other dragonflies humming above the disused nymphal exoskeletons still clinging to the bulrushes.

This morning I stand in amazement at the show before me. Hundreds of adult dragonflies going about dragonfly business. It is a harried, frenetic existence they live. The life in the air lasts but a few weeks, and much must be accomplished. Territory must be defended. Meals must be had. Mates must be found. Dragonfly business fills the morning stillness with an audible buzz. As in the water they are in the air—apex predators of the insect world. With voracious appetites they consume up to one-fifth their body mass in insects per day. Agile acrobats of the air, flying effortlessly in six directions—left, right, forward, backward, up, down. No insect prey stands a chance. The dragonfly’s keen compound eyes detect a world open to predation. Jerking forth in mid-air, the dragonfly snatches a housefly. It is time for a meal.

I crouch down to where the dragonfly has just landed on a narrow branch. It doesn’t seem to notice its inquisitive observer. Instead it’s just busy consuming its meal. The hapless fly is clasped in the dragonfly’s maxillae, its mandibles pull off the wings. The dragonfly then uses its rugged labrum to grind down the housefly into small pieces. Rotating the housefly around with its mandibles, the dragonfly’s meal resembles an apple being eaten. Minutes later, all evidence of the housefly’s existence is vanished—it has been integrated into the pulsating body of the dragonfly.

With a sudden jerk, the dragonfly launches itself in the air. It starts off as quickly as it had stopped. The dragonfly rejoins the hovering mass in the morning light, searching for its next meal. I watch in fascination; I can’t go on just yet. Though the dragonflies share in my presence, they remain indifferent. The spring generation has reached maturity and have bigger issues on their minds. Soon they will mate and lay their eggs back along the water’s edge where days ago they emerged. The spring influx of dragonflies will then dwindle. The aerial beasts will die and disappear. But the eggs have been laid and the mission completed. A year from now there will be more dragonfly mornings to come.

Do You Smell?

Do you smell?

The aromas of life surround you. Do you smell them?

What is it about an odor that can take us back, transport us somewhere different? A subliminal scent registers deep in the brain, evoking connotations of time and place. Do you remember those smells?

The pungent acridity of freshly cut grass and the distant earthy wafts of freshly spread manure arouse memories of a childhood spent in a suburban town encroaching into the countryside. My nose fondles the familiar scents as precious childhood souvenirs.

Wherever I am, the scent of a warm spring rain causes me to linger. That smell—that particular scent—is the essence of my aromatic association with home. The warm humidity of spring rains coat my nostrils, embracing them in a comfortable caress. The very sensation of humid air is far removed from the arid climes where I’ve spent the last three years. Nostalgia overtakes me whenever that sensation of the rain presents itself.

I was always told that the smell of spring rain comes from the worms. But the scent of worms alone could never do justice to the depth of the aroma. The scent is fundamentally deeper than that, nothing less than Petrichor—from the Greek words petra for rock and ichor for the blood of the gods. The fragrance of earth pours forth from the bedrock. The scent of spring rain is none less than the blood of the gods flowing through the ground.

The earth comes alive during spring rains. Soil microbes thrive in the warm, damp soils of spring, producing geosmin, the scent of the earth itself. Again a Greek construction, geosmin combines the words for the earth and the word for smell. Over winter the earth’s biotic community slackens its pace of life. Metabolic excrement accumulates in the soils, waiting to be flung into the air upon impact by rain. Spring rains re-awaken the soil microbes from winter dormancy, releasing even more of the distinctive geosmin fragrance. This is the smell of life emerging once again from the slumber of winter. Do you smell the very scent of life stirring?

I’m in the Boundary Waters Canoe Area right now. I’ve never been to this place before, but the scent brings me somewhere familiar. Is it the smell of the northwoods forests? Pine, spruce, fir, birch and aspen, all mixing their pheromones together in a melody of fragrance. Spring fecundity spreads through the air. Prolonged exposure to the scent of these northern forests registers deep in my mind. Yes, I have been here before. Not the Boundary Waters specifically, but to this place in general. The scent here is as much about where I am physically as about where I’ve been emotionally before. I ruminate with the old familiar smells. Comforting, inherently wild but familiar enough to feel homey and lived-in. Yes, I have smelled that before; yes, I have been here before.

The aromas of life surround you. Do you smell them?

Saving Lives and Taking Names

The classroom is lined with bruised and bloodied students, oblivious of their apparent injuries, all sitting at attention ready to learn. Though the injuries may look severe or concerning (especially the occasional impaled object), everything here is purely superficial, the product of realistic special-effects make-up used in class scenarios. Although each student is cured of their ails at the end of each scenario, the special effects make-up stays on long afterwards, a constant reminder to the students about the nature of their studies.

This classroom scene is from a Wilderness First Responder (WFR) course. The WFR (verbalized as ‘Woofer’) students are here to learn the fundamentals of wilderness medicine. Over an intensive eight-day schedule, students go from learning about the critical systems of the human body to applying such knowledge in realistic scenarios of wilderness medical emergencies. The aim of the WFR course is to teach any interested person enough to be able to safely assess and evaluate any emergency situation and provide basic life support to each patient when in a wilderness setting—that is, when definitive medical care is at least two hours away. Medicine in the wilderness context is made more challenging by the lack of medical supplies and a setting that is often hostile to medical emergencies and the rescuers. Thus, WFR students are taught a holistic program of extended patient comfort and care in the wilderness and are encouraged to improvise tools from outdoor gear when medical devices are scarce.

A WFR course attracts an affable and often young group of similar-minded outdoor enthusiasts. Such personalities come with the terrain. Many enrolled in the course are burgeoning outdoor professionals—guides or instructors—but some also take the course for personal development. All share the general desire to help others in emergency situations in the wilderness. With a common interest in the outdoors and backcountry medicine, and with so much class-time spent together, a class group dynamic forms with its unique bond. Being comfortable with the other students in the course is essential too; as a very hands-on classroom setting, WFR students get close and personal in the process of learning: performing spinal palpations, simulating rescue breathing, backboarding, and much more. Having a WFR course taught at a roadless camp in the Boundary Waters Canoe Area also doesn’t hurt the sense of group formation. Classroom time is shared, but so are meals, lodging, and recreation time in this residential setting. The aura is one continually steeped in the learnings of backcountry medicine.

The WFR curriculum carries no pre-requisites. Class instruction takes the student from the ground-up and quickly builds upon newly acquired knowledge. Starting with the basics, students learn about the three critical life systems of the respiratory, circulatory, and neurologic systems in the patient primary assessment. A deficit in any of these three critical systems could entail death to the patient within minutes. Simple, early scenarios in the course cement the concepts of checking each patient for these critical systems to safeguard each life in immediate danger.

Once WFR students master the basics, they soon learn more about advanced topics—a wide variety of serious and not-so-serious medical conditions. Patients with intact critical systems get a thorough secondary assessment in the field that can uncover many other challenging problems. Discoveries made on the secondary patient assessment will lead to the decision of an urgent evacuation, non-urgent evacuation, or field treatment of the patient. A traumatically injured patient may soon go into shock and need to be evacuated immediately, whereas some simple joint dislocations can be reduced in the field allowing a trip to continue. All problems, from critical to superficial, become the territory of the well-trained WFR.

The apex of practical training in the WFR course comes towards the end, when students put their new skills and knowledge into practice in realistic full-scale simulations of medical emergencies. This is where the special-effects make-up really comes into play. The course instructor will set up a medical scenario in the woods—be it a storm during a canoe trip or a mass rock climbing fall—and use some students as patients. Student-patients get a list of injuries to act out in a scene; fake bruises and blood add to the realism. Other students in the course then serve as rescuers in the scenario, approaching student-patients with little prior knowledge of the scene. Using their newly acquired knowledge, student-rescuers need to perform patient assessments and treat injuries in the field as if it were a real emergency. Even after only eight days of training, the student-rescuers perform their job with a high degree of skill and knowledge. Mistakes are still made in these simulations, but class debriefings help both patients and rescuers understand what went well and what could be improved. Afterwards, student-patients and student-rescuers switch roles to practice additional medical scenarios. One can learn just as much about wilderness medicine by being a patient as by being a rescuer.

Certified WFRs are everywhere. We look just like any ordinary person. You may see us in a city or encounter us in the great outdoors. When the situation arises, we are trained and prepared for the emergency. And we may just be the ones who can save a life.

Go Find Yourself

My travels in Australia could have been cast as the prototypical coming-of-age journey: a young man goes to a far off land alone to find himself.

But I didn’t go to Australia to find myself. I knew too much of myself already. Instead, venturing to Australia was more an exercise in trying to lose myself—to get out of the person who I knew too well and to try a different lifestyle for a change. Australia would be a place I could be free to experiment with identity.

Young people finding their identity is perhaps the defining mark in the transition from childhood to adulthood. As developmental psychologist Erik Erikson would describe it, the primary existential question of emerging adulthood (Stage 5) is that of Identity versus Role Confusion. Classically portrayed as the angsty teenagers’ struggle for self, this stage of psychosocial development often lasts into young adulthood, ending when the individuals’ personal identity becomes fairly consistent for the remainder of life. Though the age individuals go through this stage varies, the greater struggles of Erikson’s Stage 5 will typically be resolved around my age, sometime in the 20’s.

Thus, going to Australia didn’t necessary teach me who I was; more so it reaffirmed who I was already. As a result, I had inherently less identity formation to undergo, and was faced instead with a related identity struggle—figuring out how to live the rest of my life with this person I’ve grown to be.

In my challenges with my identity, there are things I know about myself that I struggle with accepting. There are some things I wish I could be just a little bit different—I’m terribly shy and introverted; spontaneity is quite a ways out of my comfort zone; I tend to take everyday matters way too seriously, etc. The list could go on about things I believe society expects me to be, but that I feel I just don’t measure up to.

Travelling to Australia, I held the assumption that going to an exotic country where no one had any pre-conceived notions about me would allow me to branch out and escape the confines of my identity—in particular my temperament and personality. For once I just wanted to let loose, be spontaneous, hang out, party, and disregard the consequences. I also thought I’d play with some career roles by trying out jobs I’d likely never do in the States—fast food drone, a sociable waiter, the hospitality industry. I’d also grow out my hair one more time before I had to permanently adopt a well-groomed hairstyle for the remainder of my professional life.

Alas, I didn’t find myself becoming the wild, long-haired, care-free holiday-maker I had envisioned before my trip. Instead, my standard temperament took the reins. In Australia I struggled to be outgoing and to meet new people; I rarely was spontaneous and light-hearted enough to party in spite of the consequences; I never found a job in the service industry; and I never grew my hair out before getting fed up with its wild antics.

In the end, I found that I just couldn’t lose myself in Australia, though I put in a genuine effort to try out different roles for a change. Instead, my reliable temperament shone through even in my new surroundings. Like Socrates’ famous mandate I just couldn’t help but to “know thyself” even Down Under.

Moving forward, my challenge is to accept myself for who I know I am instead of thinking that a different persona is more desirable or acceptable. How can I make the best use of the character I’ve developed? What role do I fit into in adult life? Instead of seeing them as weaknesses, how can some things about me that I’m uneasy about be used as assets?

Going to Australia may have been the final throes of my greater struggles in Erikson’s stage 5. Sensing that I was nearing a very stable sense of self, I felt the necessity to try on different roles while I still had the freedom to experiment. For the most part, though, my personal character has cemented, deepened in part by the challenges I presented myself in Australia. Some conflicts of Stage 5 still remain, namely those of finding a career path and determining my role in the adult world. But on the whole, the person who I am today is the person I have found and have chosen for myself. For all its strengths and seeming inadequacies, I’m happy for that person.

The Graduate

About this time last year I graduated from the University of Idaho with a masters degree. Being mentally and emotionally drained from formal study, I was ready to leave the cloistered realm of academia and explore the greater world on my own terms. So excited was I to get a jump start on my informal education that I left exam week early and skipped my commencement ceremony in favor of a kayak trip on the Columbia River.

Now that it’s graduation season again, perhaps I should be granted another diploma. Conceivably it could be from the University of Wanderlust. It wasn’t an accredited university. It had no designated faculty, and there were no required courses or class assignments. Tuition was also pretty inexpensive (although room and board could be costly at times). Although there were tests along the way, the entire grading system was based on pass/fail.

Yes, now that I’ve officially ended my coursework of travels, I’d say it’s like I’m a freshly-minted grad once again. My degree from the University of Wanderlust ended up being a year-long program (or else I guess I just graduated early), and I was happy to build my own curriculum too. First I spent a semester in the American West, road-tripping on a survey course of National Parks and cultural highlights. Then, I spent my second semester in Australia, taking classes in fruit-picking and van culture. From this I’ve earned a diploma full of different life experiences at an expedited rate.

And what’s more, my diploma from the University of Wanderlust focused on personal change as much as it did about learning factual knowledge. Though I enjoyed learning a great deal about many of the spectacular places in the United States as well as learning about the way of life in a foreign land, what I had set out to gain through my latest degree was deeper—a more thorough understanding of my own personal growth and moral development. My masters degree at the University of Idaho, though it challenged my intellect, lacked much of the personal growth I yearn for in education. What I needed to compensate for this lack was a challenge to develop my character and to gain a different perspective on the world.

Unlike a typical college education, though, my self-designed degree focused more on the realm of the practical rather than the theoretical. Throughout my travels, challenges were applied and consequences were real. Every event was viewed with the mindset of an opportunity to learn. Daily life became my homework assignments and the people I met along the way were became my professors.

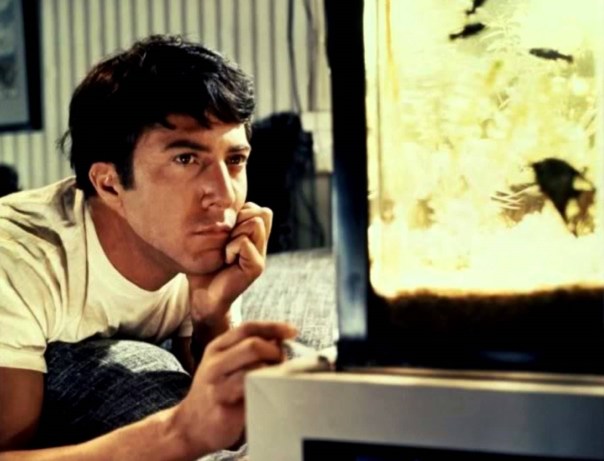

As a recent grad of the University of Wanderlust, I feel fresh and ready to pursue a career path. Admittedly, I still do feel a little bit of the aimlessness and uncertainty of recent grad Benjamin Braddock from Mike Nichols’s film The Graduate. But on the whole, my diploma of travel in the real world has provided the necessary transition from the culture of the academic world to the culture of the working world.

Many of my lessons learned from the University of Wanderlust still need formalizing into words. But how does one succinctly sum up a year of travels? Fortunately for me (or maybe not!) I never assigned myself a term paper.

Leaving (Many) Stones Unturned

This is my first blog post back in the United States. Yes, that means my Australian adventure has ended. What I initially intended to be a year or more of work and holiday in Australia concluded after spending a comparatively short 187 days in the country.

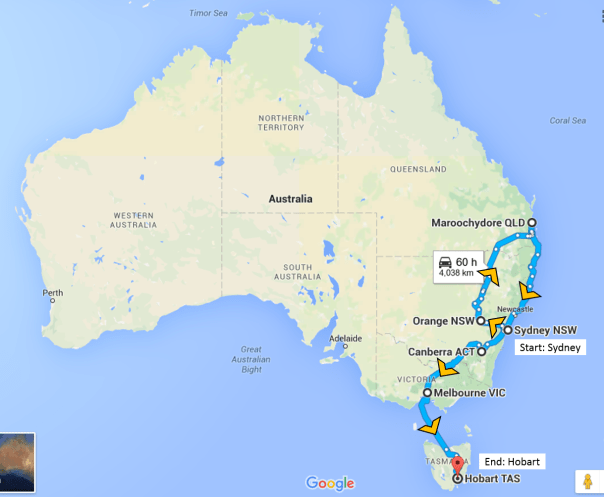

In an earlier blog post, I summarized an outline of the itinerary I had conceived for Australia. It was an ambitious plan for sure—my goal was to drive around the whole country and experience all the best that Australia had to offer. Seeing how this trip would be my only working holiday visa in Australia (and in all probability my only visit Down Under), I wanted to make the most of it. With the naïve idea that I’d be able to see everything worth seeing in Australia, I calculated a very thorough travel schedule so that I wouldn’t have to bother coming back to the country. After all, it was a long 15 hour flight from Los Angeles to Sydney just to get to Australia. Below is a map of what I originally envisioned for my year+ Down Under:

Needless to say, things didn’t work out very much as planned. Good, equitable work was difficult to find; shady fruit picking contractors swindled me out of a good chunk of my meager earnings; and my campervan experienced breakdown after breakdown. The accumulation of adverse experiences in Australia eventually led me to abandon the working holiday dream altogether. Though fate didn’t seem to be on my side, I don’t regret the journey at all and felt like I learned many invaluable lessons that I couldn’t have learned otherwise. Practically, though, as a major consequence of the essential unpredictability of eking out an existence in a foreign land, my idealized Australian itinerary changed drastically. Here is a summary map of where I actually traveled:

Probably the most noticeable difference between my idealized itinerary and my actual itinerary is the extent of the travels. Though I put over 15,000km on my campervan, I still only covered a fraction of the Australian continent. Major destinations like Queensland’s tropical north and the Outback’s red center were never reached. Travels to Western Australia and the Northern Territory were scrapped from the plan entirely.

Though I am disappointed at not being able to see such remarkable places, I’m not distraught over the lost opportunity. In conversations about my Australian trip, people often remarked that my journey was a ‘once-in-a-lifetime opportunity’. And, while making my plans for Australia, I took that sentiment to heart. I preconceivingly figured that I would never travel to Australia again—that this particular Australian trip would be my only chance to see places of world heritage value like the Great Barrier Reef or the Outback. Thus, I wanted to make sure I uncovered every stone Australia had to offer, so I could forever check the continent off my bucket list.

Abrasive reality—and sheer practicality—saw through my meager attempt to see everything in Australia. It is an impossibility to overturn every stone and leave nothing new to see in a country. Even if someone were to visit every square meter of a place, they would still have more to discover in the nooks and crannies. Such a person would still need to see the same things again, but from a different angle. Such a person would still need to spend more time in the country just to understand how the incessant elements of time and change affect a place. Fully seeing everything a country has to offer as a visitor is an absurd notion indeed.

As it so happened, I left many stones unturned in Australia. Though I wish I could have stayed longer and traveled more, I’m happy to say that I still have many reasons to go back to Australia in the future. Though I have no definite plans to revisit, I can see scenarios of returning soon to my much favored Hobart town for graduate school, or of returning only after many decades have passed as a grey-haired tourist. It’s also quite possible that I may never return to Australia again. But one things for sure: I never want to think of my stay in Australia as only a ‘once-in-a-lifetime’ opportunity.

Ghosts of Port Arthur

Recently I took a journey to see the ruins of Australia’s most renowned convict site, the penal camp at Port Arthur, Tasmania. Looming sandstone ruins lie sullenly at the site; their walls remain silent yet beckon the visitor to come closer. Port Arthur is rumoured to be decidedly haunted. On a gloomy day, one can nearly hear whispers from the horrors of convict transportation. Upon reforms of the penal system, transportation of British convicts to Van Diemen’s Land (modern Tasmaina) ceased in 1853, and Port Arthur finally closed as a penal site in 1877. Soon after its closure, Port Arthur became a tourist attraction for those curious to learn about the depravities of humanity that occurred there.

The ruins of Port Arthur, Tasmania

The oldest buildings at the Port Arthur site date from the mid-1800’s. Today these old sandstone edifices stand as hollow shells after bushfires gutted the buildings post-abandonment. However, one modern building on site also stands as a hollow shell—a memorial to another dark time in the Australian nation’s past. This building is the Broad Arrow Café, the site of Australia’s worst mass shooting in national history. On April 28, 1996, a lone gunman walked into the café and opened fire, initially killing 20 victims in a shooting spree that would go on to take the lives of 35 and injure dozens more.

The Broad Arrow Café.

I was alive when the Port Arthur massacre took place. I was five years old at the time, older than the youngest victim, but too young to understand even if I had known what had happened. In no way do I have personal connections to the Port Arthur site—yet I still felt drawn to the memorial as a sacred pilgrimage. As an American, I am a citizen of a country that knows gun violence too intimately. I can’t help but feel sympathy for those whose lives are devastated from senseless violence. Akin to a stranger mournfully walking through an unfamiliar cemetery, I felt the need to pay my respect to those who had died in the Port Arthur tragedy and, symbolically, to others in similar incidents around the world.

Only a few weeks into my travels in Australia, America once again faced the consequences of another mass shooting. December 2, 2015, San Bernardino, California. The news broke from the TV in the hostel I was staying in. Though I don’t even watch television, I couldn’t pull myself away. Before San Bernardino, I had always stayed informed on the all-too-many mass shootings in America. But this time I was watching from abroad. I had become a distant observer behind a glass panel. Witnessing the events from abroad, I couldn’t help the overflowing sadness of lament for my country, a land that allows such tragedies to happen continually. I felt angry at the ineffectiveness of any sort of reform that would unite my country to curb the violence. That morning I shed a tear of sorrow for my country.

I visited the Broad Arrow Café at Port Arthur thinking that I’d learn a lesson on how one nation responded in a unifying manner to prevent future tragedies from happening. But gun control lessons weren’t the point of the memorial. The empty shell of the café is rather a somber place to mourn for those 35 taken. It’s a touchstone for reflection.

In matters of gun violence, the difference between Australia and America is that one country was united enough by tragedy to act. In the wake of the 1996 massacre, strict, nationwide gun control laws were passed—semi-automatic assault weapons were banned, a nation-wide gun registry was implemented, and gun buy-backs were held. Australia soon developed one of the most regulated gun markets in the world. As a result of the reforms, gun violence in Australia plummeted drastically. A telling sign of the effectiveness of one country’s reaction is that no mass-shootings on the scale of the Port Arthur Massacre has occurred in Australia since.

Places like Port Arthur stand as a sentinel to the past. We remember and sojourn to these places because we can learn from the mistakes of days gone by. The convict transportation system at Port Arthur shattered lives with its cruel ad unjust punishment, just like a mass shooting at the site shattered lives 20 years ago. I want to believe we can learn from the mistakes of our past and forge a better future. I want to believe we can unite and act before more tragedies occur.

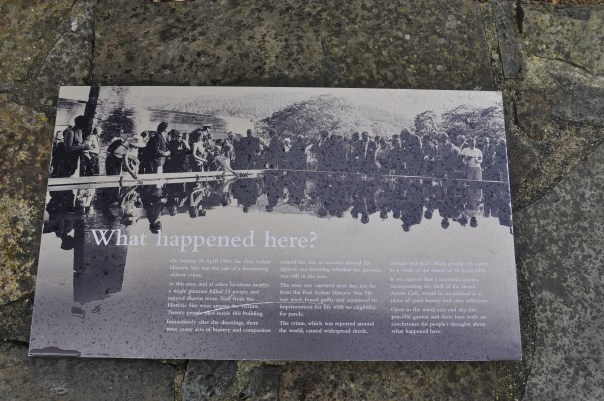

Memorial Plaque at the Broad Arrow Café.

Transcript reads:

What happened here?

On Sunday 28 April 1996, the Port Arthur Historic Site was the site of a devastating violent crime.

In this area, and at other locations nearby, a single gunman killed 35 people and injured dozens more. Staff from the Historic Site were among the victims. Twenty people died inside this building.

Immediately after the shootings, there were many acts of bravery and compassion around the site, as rescuers tended the injured, not knowing whether the gunman was still in the area.

The man was captured next day, not far from the Port Arthur Historic Site. He was tried, found guilty and sentenced for life with no eligibility for parole.

The crime, which was reported around the world, caused widespread shock, outrage and grief. Many people still suffer as a result of the events of 28 April 1996.

It was agreed that a memorial garden, incorporating the shell of the Broad Arrow Café, would be established as a place of quiet beauty and calm reflection.

Open to the wind, rain and sky, this peaceful garden and these bare walls are touchstones for people’s thoughts about what happened here.

The Passionate Lot

Doing so much travelling around lately, I have found it a great pleasure to go to unique little places where people’s passions are on display for any wayward visitor to share in. Lots of these places may be small, under-recognized, and out of the way of the main tourist haunts. Sometimes you just happen to stumble upon them, like a nugget of treasure. But wherever you have passionate, dedicated people, you’ll find the special places they have created to share. In addition to the individuality of the sights to see, it is the enthusiasm given by the creators of such places that makes visiting truly a momentous occasion.

Traveling between Sydney and Melbourne, I stopped at a few places off the beaten path and was pleasantly surprised at what I found. The places I visited stuck in my mind mainly because of the passionate and dedicated people that stood behind the projects. It was a joy to get to see the talents of others on display. Here is a sampling of some of these places I went:

- Rusconi’s Masterpiece, on display in Gundagai, New South Wales. Frank Rusconi was an Australian-born and European-trained sculptor, who dedicated his life to marble craft. Rusconi carved many magnificent sculptures and monuments throughout Australia, but perhaps he is most well-known for his marble masterpiece. Not just a sculptor by trade, Rusconi was a sculptor by hobby as well. Every day for 28 years, Rusconi would spend three hours at night working on his masterpiece castle of 20,948 individual pieces of Australian marble, meant to showcase the fine quality of marble on the Australian continent. Rusconi’s masterpiece was later donated to the public for all to see his craft.

- The Ned Kelly Animatronic Show in Glenrowan, Victoria. In Glenrowan, the location of infamous Australian bushranger Ned Kelly’s last stand, there is an animatronic re-enactment museum of the Kelly gang’s famous gun battle with colonial police. With a kind of dark Disneyland-ish aura, the experience takes visitors through a half-dozen rooms all depicting various stages of the Ned Kelly siege. In each room scenes were set up using mannequins and animatronics that tell the story; so involved is the realism that smoke will pour out of the burning hotel and Ned Kelly will make a surprise drop from the ceiling as he is hung by the police. With how well the show is put together, it might very well seem that the animatronic museum is new and uses advanced technology. But no, the 80-year old purveyor explained, he’s been working on the display over the last forty years. Though the old purveyor himself was slowing down due to age, he eagerly explained how his 20-year old grandson was keen on taking over the operation in the future.

- Cactus Country gardens in Strathmerton, Victoria. The cactus is not native to Australia, but it thrives very well in the arid climate nonetheless. Australia’s largest cacti garden, Cactus Country, is a testament to that fact, as well as a testament to owners Jim and Julie’s dedication. The seeds of Cactus Country were started in 1979, when Jim purchased his father’s cacti collection shortly before marrying Julie. Together they set upon creating the largest cacti display Australia has ever seen, and Jim and Julie continue to expand their 10-acre garden to this very day. I was very pleased to have run into Jim in the garden. After all, it’s not every day you can have a long conversation about cacti with a stranger.

Marble sculptures, animatronic bushrangers, and cacti gardens may not have a lot to do with each other intrinsically, but in this case they are all interests undertaken by passionate people. Some very talented people hide their talents and skills from the world. However, there is a passionate lot who put their skills on display for all to see, thus creating these places worth visiting. It isn’t always intentional either—passions pursued for their own ends will often become compelling enough to attract visitors. Meeting the people behind the work and experiencing their contributions is a real treat for the tourist-trap weary traveller. It makes travelling the backroads even more special.

Aussie Bush Tucker

I’m venturing into the genre of culinary blogging! My first meal will be for some Australian Bush Tucker—in American speak, that means food from the Australian wilds. To make it authentic bush tucker, I foraged my ingredients from the wild bush* of Australia.

*by ‘wild bush’ I more accurately mean urban landscaping!

Appetizer: Macadamia Nuts

Macadamias are in fact native to Australia, growing wild around the eastern New South Wales/Queensland border. The macadamia also happens to be the only native Australian food that has a significant economic industry associated with it. Though my readers may be familiar with the food, they may not be familiar with how the nuts come to the table.

Macadamias nuts are, as expected, the nut of the Macadamia tree. The nuts grow in clusters on small evergreen trees, ripening in summer. The young nuts are enclosed in a green woody husk. As the nuts mature and dry, the husk will turn brown and split open and the husked nuts fall to the ground.

Eating Macadamias is fairly simple—or at least it should be! Though the dried husk is easy to remove, the rest of the Macadamia proves to be one tough nut to crack. Sad to say my humble nutcracker sacrificed its life in this meal endeavour. In cracking the nuts, the shells are able to sustain so much pressure that when they finally do crack, the nut shrapnel fragments fly everywhere. Any of the ivory-coloured kernel that can be recovered afterward has a most excellent tasting smooth and nutty flavour. Macadamias can be eaten raw, as I did, or prepared through other methods such as roasting or baking.

Main Course: Bunya Pine Nuts

The Bunya Pine, though the name would imply otherwise, is not an actual pine. It is a more ancient form of conifer of the family Araucariaceae, which thrived in the time of dinosaurs but now is limited to a few species in the southern hemisphere.The Bunya Pine’s native range is restricted to Southeast Queensland, though they also are a widely-planted landscape tree. The trees grow to be tall and straight, with tough, spiky evergreen foliage. Better watch out when the Bunya Pine cones fall—they’re about the size of an adult’s head! Cockatoos also feed on the Bunya Pine nuts, opening the cones with their beaks and letting pine nuts fall to the ground.

The Bunya nut was extremely important as a food source for Aboriginal peoples, who would travel vast distances overland to reach the locations of Bunya pines to feast on the nuts. Great festivals would be held as neighbouring tribes set aside their differences to share in the feast. The Bunya nuts could be roasted over a fire or ground into a flour and baked into a bread.

I decided to boil my Bunya nuts. Though the nuts are protected by a tough, fibrous shell, the shell will soften and split upon either roasting or boiling.

I boiled my Bunya nuts for about 15 minutes, until the shells became soft and easily opened. The boiled water collected the tannin from the nuts, producing a dark, piney tea.

Opening the shell and getting the nut out proved to be a labour-intensive task (though considerably easier than cracking Macadamia nuts!) The shell splits along two seams, allowing a flap to be pulled back enough to allow the nut to be freed. The cooked nuts resemble giant garlic cloves, complete with the embryonic plant in the middle of the white endosperm. Eating the embryonic plant gives the most piney flavour. The startchy endosperm, in contrast, tastes akin to a potato—though instead of a smooth consistency, the nut is much more rubbery.

To supplement the little flavour in the Bunya Nuts, I doctored them up with cheese and salsa. Voila—an Australian meal of loaded Bunya Nuts. Similar to loaded baked potato, but a whole lot chewier.

Home is Where the…(wherever)

The skyline of Hobart, Tasmania nestled between the sea and mountains

space

“This is the most beautiful place on earth. There are many such places. Every man, every woman, carries in heart and mind the image of the ideal place, known or unknown, actual or visionary. There’s no limit to the human capacity for the homing sentiment.”

-Edward Abbey, Desert Solitaire

space

One challenge for my time in Australia was to come up with a definition of what home means to me. The origin of this question goes further back, though, stemming from several protracted conversations with friends on the topics of home and place. As part of a generation coming of age in an increasingly globalized society, the question of home is no longer as limited as it used to be. Instead, rapid global travel and communication technology allow for a more mobile and connected society. Our options of where to live, work, and play quite literally span the globe. Yet, the idea of discerning one’s home in the vast world still constitutes a fundamental part of our identity.

As for myself, I feel like home could be anywhere. That’s to say that home isn’t necessarily a physical location in particular, but an idealized interaction with a location in general. Though I have travelled through admittedly very little of the world and have not experienced substantially different cultures, I can see a trend in my interaction to new places. Foreign locations become less foreign with familiarity. Given enough time, I feel that eventually I could make a home on any corner of the planet and be content with that location. This is not a judgement of place, but a judgement of my interaction with places. Home, then, is a process. It’s the homing sentiment.

Fundamentally, to me the question of home comes down to the concept of rootedness. How rooted do I feel to a certain place? My answer to that question is that I’m yearning to be rooted to any place at all. I struggle greatly through my travels with feelings of transiency and impermanence—essentially a new kind of homelessness. I yearn to be connected to a place at a more than superficial level, and any place could ultimately fill that desire. This is why, among other things, when I’m travelling I feel the need to stop at interpretive signs detailing local history—about the actions of city residents long dead or buildings long ago razed even though it may have little personal meaning to me at the moment. Doing such is just one small tangible way of discovering more about a place that leads me to a feeling of connection—that I belong more to a place now that I know more about it.

Given enough time, my habits of interaction with unfamiliar places should lead to a greater sense of home within each place I stop. Along with my habit of learning local history, I also tend to eschew corporate retailers in order to patronize businesses I could find nowhere else, take ambling walks along city streets to understand geographical differentiations within the city, and take note if I see local faces more than once. In short, in each new place I try to understand the local identity. I try to live like a local. This, fundamentally, is the reason why I feel like I could find sentiments of home in any geographical location.

However, though I feel like any geographical location could ultimately become a satisfactory home, some places I visit certainly seem more likely candidates. As someone who studies the natural environment and geography, the landscape—physical and cultural—plays an elevated role in the homefulness of a place. In my Australian travels, some places lend themselves more readily to sentiments of home; towns like Orange, Tumut, or Hobart sparked a sense of rootedness in me quickly. Other places, such as Maroochydore, felt reprehensible at first but inevitably grew on me endearingly. If nothing else, my period of meandering travel in Australia has helped me refine the qualities of a place that most readily resemble a home for me.

In a globalized society, the whole of the earth could theoretically be my home. Such possibilities create a world of geography to navigate in finding one’s place. For me, home is still an ongoing conversation, and I still have a lot of geography left to navigate.

***

‘I cannot honestly say that I liked Canberra very much; it was to me a place of exile; but I soon began to realize that the decision had been taken, that Canberra was and would continue to be the capital of the nation, and that it was therefore imperative to make it a worthy capital; something that the Australian people would come to admire and respect; something that would be a focal point for national pride and sentiment. Once I had converted myself to this faith, I became an apostle.’

-Former Prime Minister of Australia, Robert Menzies, reflecting on his changing attitudes towards Australia’s national capital Canberra.