Crepuscular Awakening

space

To go in the dark with a light is to know the light.

To know the dark, go dark. Go without sight,

and find that the dark, too, blooms and sings,

and is traveled by dark feet and dark wings.

–Wendell Berry, “To Know the Dark”

space

There is a certain phase between day and night, a time of transition, where the diurnal blends into the nocturnal. These periods of emergent light and shifting darkness make up the twilights of the day—the bimodal intervals between dawn and sunrise, and between sunset and dusk. This is a time on the edges, on the border of binary classification. Organisms that make their way about in these in-between times are known as crepuscular. Those active strictly in the morning twilight are the matutinal; those active solely in the evening twilight are vespertine.

Many familiar creatures make their way about in this altered level of light, taking advantage of both the dimness and the illumination. This is the time to be crepuscular. Under these conditions, a multitude of large forest dwelling creatures emerge—bear, deer, moose—along with their small mammal compatriots: skunks, raccoons, possums, rabbits. Many creatures of the air take flight. The insects—mosquitoes, moths, fireflies. The birds—the owls, the nighthawks. The charismatic bats also take wing. It is now that the active behaviors of these creatures peak. To bear witness to these crepuscular awakenings, the intrepid observer must come join the experience, without light, as a member of the dark.

You are in the middle of it now. Let your feet and voice be silent as you travel in deeper. You will find that the woods are alive with sounds and movements. Careful! Listen close! You too will hear and know the character of the fading light. Though the growing darkness distorts your human vision, fear not. There is nothing to be afraid of in these woods. Nothing in the night is any more dangerous to you than during the day. With transformed senses and unfamiliar sensations, your mind fills in the gaps and imagination runs wild. Yet don’t be alarmed. These crepuscular creatures are more afraid of you than you are of them. Relax. Stay a spell. You may become privy to the hoot of an owl or catch the gliding wisp of a bat overhead.

This twilight journey has been a distinctive experience for you, for humans are not crepuscular creatures. We are largely diurnal, adapted to the brightness of day. Our main sensory experience, our vision, works best in broad daylight. As the day fades into twilight, our eyes begin to cope. The iris expands and the pupils dilate to allow in the dissipating light. Inside the eye, the cones—the sensory cells that detect color and detail—begin to shut down in the dimness. Colors begin to fade, details blur. The acuity of vision diminishes. Yet within the eye, the counterpart of the cones—the rods—begin to become engaged. With the activation of the rods, contrast and shadow become keener, movement more detectable. The silhouettes of trees overhead begin to pop against the dimming sky. The rods readily pick up movement in the periphery of your vision. What was that?!? Did something move? In your periphery, you may detect movement, but oh what tricks your mind may also play on you! The darkness is unfamiliar territory; you are more wary, more attuned to sudden movement.

Yet there are creatures about. There is an abundance of life that is indeed adapted to the crepuscular world. The fading light offers a veil of protection for easy prey, yet illumination enough by which to forage. Predators, too, make use of the twilight as a time of feeding. Equally adapted to the hunt, the crepuscular predators seek out their crepuscular prey. In the twilight, the never-ending battle of evolution ebbs on. Owls, marauders of the night sky, have large eyes adapted to gathering the few rays of light available; binaural hearing, also known as asymmetrical ear placement, allows the owl to detect differences in sound occurrence down to 30 millionths of a second, letting them pinpoint even the tiniest rustle on the forest floor. Overhead the sky is filled with the noise of sound waves, inaudible to the human ear. The bats have emerged and fill the night sky with their echolocation. By emitting their sonar in flight, bats are able to precisely locate the abundance of crepuscular insects upon which they feast. It is a world of eat and be eaten.

All daylight has now faded. At astronomical dusk, the light from the sun no longer can reach over the horizon—it is now as dark as it can get. The period of crepuscular animals is ending. Patiently they will wait again until the next time of twilight. Truly nocturnal animals now make their way about the forest. Take a moment to gaze up now. The sky abounds with a brilliance of stars. Even in the dark, light from a thousand distant suns still caress the planet with their brightness. Even in the darkness, there is light. Even in the darkness there is knowing.

To the Spiders in the Bathroom Corner

“I seek a garret. The spiders must not be disturbed, nor the floor swept, nor the lumber arranged.”

* Henry David Thoreau *

There is a congregation of spiders who reside in the corners of my bathroom. Inverted, they hang from the ceiling, by day and by night. They are small-bodied creatures; their combined head and thoracic sections—the cephalothorax—is rounded into a light-brown disk no bigger than a lentil; the abdomen, dark brown and cylindrical, the size of a peanut. The body is flanked on both sides by long spindly legs, light-tan as the thorax but with kneecaps of auburn. Chelicerae hang abruptly from the mouth like two tiny stilettos. Taken together, these parts compose a graceful creature—thin, delicate, fragile. A handsome specimen of nature.

But how did they get here? How did they arrive in this indifferent human world so far removed from the wild? There is no window in the bathroom, no apparent opening to the outside world. No cracks in the walls seem large enough for them to squeeze their gangly legs through. Surely they have not crawled out of the drain, for they do not seem to like the moisture—they spend their lives on the near-side of the bathroom, far-removed from the dampness of the shower. Have they spontaneously arisen from the lavatorial miasma?

And why are they here? Why have they arrived, and how did they find their way? Are these creatures lost souls in an alien human habitat? Are they, perhaps, just frightened émigrés huddled in a dry corner, fearful of the strange land they have stumbled upon, haunted by the large creatures that repeatedly visit? Do these spiders even recollect the outdoors or pine away for its presence—a storied, sylvan world now lost to them?

Maybe they have spent all their lives here. Maybe they were born to a generation of bathroom-dwelling arachnids, generation after generation after generation. Maybe the barren corners of the bathroom ceiling is all they have known. Despite their mysterious origins and incongruous circumstances, theirs seems to be a contented life. Though resplendently graceful, they seldom move. They stand an enduring guard over the sink and toilet, watchmen on an eternal silent vigil. Quiet, monastic, unhurried. Ever present, ever-vigilant. They lead lives of amity.

Their webs, if they do make any, are non-descript. Invisible. Wispy cobwebs of fluffy silk bundled in the corners, of seemingly no practical use. Inside, there appears to be no insects victimized. In fact, the spiders seem to share the bathroom with no fellow invertebrate dwellers. From where do these spiders get their sustenance? Do they eat at all?

I’ve chosen to live with the spiders in the bathroom. They are not demanding guests. They cause no fuss. Their presence has become part of the décor; I can no more think of the bathroom without thinking about the spiders that inhabit it. Why spoil the commensal relationship we have together, out of a desire to clean and tidy? No, these creatures are part of the home, welcome as a cherished guest. They have just as every right to exist and inhabit this space as we do. We and the spiders, both fellow creatures adorned on our home the earth together, seeking out our livelihood whichever way we can.

Making the House Ready for the Lord

Dear Lord, I have swept and I have washed but

Still nothing is as shining as it should be

For you. Under the sink, for example, is an

uproar of mice – it is the season of their

many children. What shall I do? And under the eaves

and through the walls the squirrels

have gnawed their ragged entrances– but it is the season

when they need shelter, so what shall I do? And

the raccoon limps into the kitchen and opens the cupboard

While the dog snores, the cat hugs the pillow;

what shall I do? Beautiful is the new snow falling

in the yard and the fox who is staring boldly

up the path, to the door. And still I believe you will

come, Lord: you will, when I speak to the fox,

the sparrow, the lost dog, the shivering sea-goose, know

that really I am speaking to you whenever I say,

As I do all morning and afternoon: Come in, Come in.

* Mary Oliver *

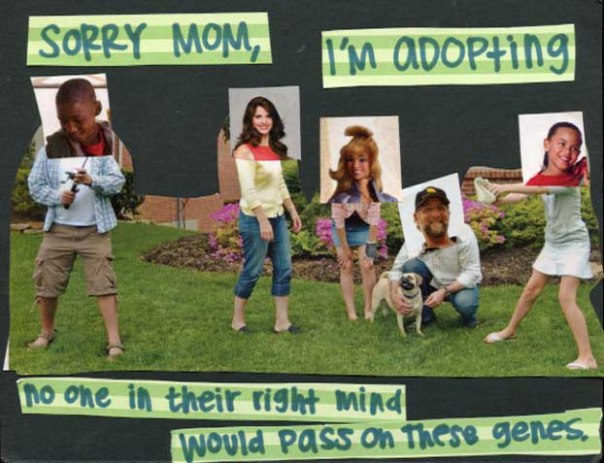

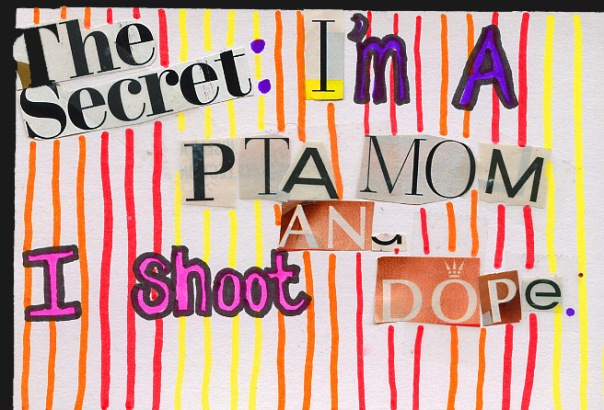

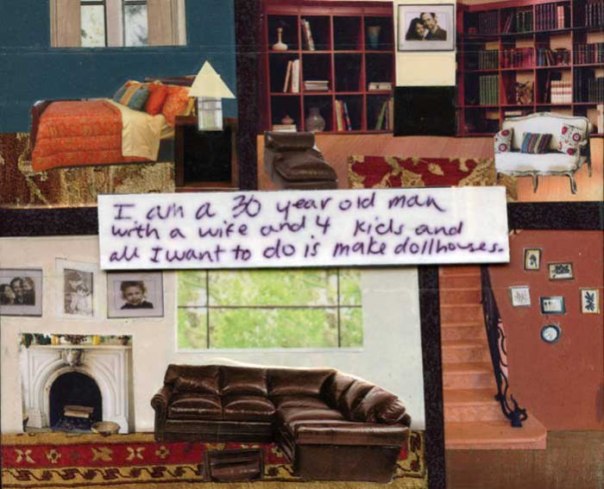

PostSecret Confessions

Dear Readers;

I have a confession. I have sent anonymous secrets through the mail to a man named Frank who lives in Maryland.

Signed,

Anonymous

What is it about secret confessions and their anonymity that draws us in? Why are we intrigued by the private admissions of others? Is it a voyeuristic thrill at becoming privy to someone else’s inner being? Is it that we feel oddly connected to the vulnerability espoused by another—a vicarious living through another’s susceptibility without having to be vulnerable ourselves?

Since 2005, there has been an active channel to send one’s anonymous confessions broadcast on a postcard via standard mail. The PostSecret project, as it is formally known, was started by a man in Maryland named Frank Warren. It was an experiment. A community-fueled mass mail art project. Confessions being mailed in had no restrictions on content or style, so long as they were true and a genuine first-time confession. Since its inception, the PostSecret project has grown into a large social experiment shedding light on the hidden side of human life. It has become a clearinghouse of secrets and confessions, both mundane and salacious. The collective consciousness of the confessions is a window into the human condition.

I find myself continually drawn to the PostSecret project. I am inextricably attracted to the struggle and humanity expressed in the postcard confessions. A simple piece of paper, an anonymous hand-scrawled message, is a gateway into the breaking down of the barriers and facades that bind us to polite society. The reader of the postcards is as anonymous as the sender, a conversation happens in which no one speaks face to face. Does the reader relate to the struggle of uncertainty and vulnerability? Is the reader only humoring himself? And how many people, if any at all, will eventually see one’s confession?

After being merely a consumer for many months, I have decided to join the ranks of the confessors. Understandably, I have sent in no groundbreaking confessions of my own. Compared to the content of many postcards, mine are quite tame. I will not spoil my secrets by publically disclosing them here. But mine have been confessions more akin to bad manners and personal oddities that don’t quite match up to social etiquette. ‘I enjoy peeling gum of off the bottoms of chairs,’ would be an example similar to the content of my confessions. It’s a small start. But it imbues a powerful feeling nonetheless.

Reading these postcards and sending in my own confessions, I feel a sense of solidarity with the community of unknown contributors. It gives me a sense that I’m not so much alone in the world. That other people, like me, are indeed strange and have many quirks and idiosyncrasies that we cover over in the going-abouts of our daily lives. Each confession sent also provides a sense of relief. A freeing feeling. A sense of liberation at getting something off your chest.

Has the PostSecret project amassed its popularity because it is so hard to be open and vulnerable? Because it is so tough to find a confidant in other people? Perhaps it’s because life is so much about image, about putting on a game face and hiding what’s underneath. We don’t normally get exposed to the nitty-gritty details that lie at the core of a person. Is it because we have a deep-rooted desire to be known and exposed that we seek to confess to others?

Posting this blog article is a confession in itself. A confession of having confessed something. But the audience remains anonymous. To paraphrase Annie Dillard, writing is the most egotistical endeavor; instead of personally telling their story to a select few people, the writer chooses instead to pursue the attention of anonymous thousands. Maybe sometimes all it takes is a nameless confession in front of a multitude of strangers to feel some sense of comradery.

Check out more about the project at http://postsecret.com/

~Or~

Send in your own secret to

PostSecret

13345 Copper Ridge Road

Germantown, MD

20874

Primitive Survival Instincts Bred in the Toxic Classroom Environment

It all changed after a series of bad days. Especially after one particularly tough day where I ended up reaching a turning point. It started, innocently enough, in a kindergarten classroom. Within the first 20 minutes of class, one troublesome boy raised both his middle fingers and yelled ‘fuck you’ to a classmate. Accepting his correction, but not changing his behavior, he continued to harass and hit other students throughout the morning. Later on, a tardy student walked into the class, promptly stealing some chapstick from another student. After refusing to correct her actions and to make amends with that student, she became defiant. “Make me, motherfuckin’ bitches,” she called out as she ran around the room, “Go ahead—call the principle. She’s a bitch!”

The afternoon, unfortunately, got worse. Instead of kindergarten, I was switched to a second-grade classroom. Older kids did not mean more mature behavior. Instead, when the students came in from lunch recess, they immediately proceeded to physically fight with one another. One student raised a chair above his head and threatened to throw it. The principle had to be summoned—the quarrelling students had to be removed. While waiting for backup to arrive, I held the most intent student back by the shoulders. He had been insulted by another student and was now deadest on pummeling him. I got down on the student’s level to reason with him. He made no eye contact, he spoke nothing. All I could see was the glazed, glowering expression of a young boy narrowly focused on physical atonement on those who he felt had wronged him.

Both classrooms ended in chaos. That school was not a safe learning environment. It was a place where physical and emotional violence was dripping at the seams. Driving home that day, I reflected on what I had just experienced. It was a lot to process. Once back to the safety inside my house, I plopped down on a chair in the living room. A visceral sense of relief finally settled over me. As I debriefed my day with my housemate, my body started to physically tremble, sympathetically, autonomically. While at school, my adrenaline was flowing in the moment as my attention was focused on the extreme behavioral challenges in the classroom. Once fully removed from the situation, my body was left quaking from the trauma of the day.

That was the turning point for me. At my third week of substitute teaching, I came to a crossroads. It was either get tough or get out. I knew I couldn’t continue in the teaching position with my idealistic attitudes of kindness and compassion. So I got tough. Instead of focusing on nurturing the development of the students, it became more imperative just to control them. It was an unfortunate reality, but this change of focus was a move for my own survival as a teacher. The situation had devolved to a point where basic jungle survival instincts kicked in.

As an idealist, I came into the job soft and compassionate, motivated by the belief that I could make a profound impact upon the youth. I wanted to look favorably upon children as kind and innocent. I wanted to run the classroom with fairness and generosity, giving the students the benefit of the doubt in all situations. Fundamentally, I wanted to foster holistic personal growth in the students—all within the short day-long duration of my stints as a sub.

Instead, I shockingly found what could become a very corrosive environment inside the classroom. These kids don’t know you, and they don’t respect you because of it. They aren’t of the upbringing where they learned to respectfully listen and obey adults or authority. To them, you are a stranger with no weight or consequence to their lives. They see you and think they don’t have to follow because “Man, I don’t even know you,” or “You’re not a real teacher.” The relationship I developed with the students never reached my idealized version of youth mentorship; instead, what organically developed was a predicament of antagonistic adversaries. As a substitute, you have to be stern and assert your authority, lest you quickly lose control of the class. You budge an inch, the kids take a mile. Eventually, you begin to develop the mentality of a prison guard controlling your wards. Your task as a sub is to force your prisoners to follow the lesson plans no matter how much they try to derail your efforts.

In the end, I became a much more callous person. My patience shortened. Authority and control became my goals—not out of a desire for control itself, but out of sheer necessity. Each morning, I had to prepare for battle with the mindset that these kids are out to tear me down. In a behaviorally troublesome classroom, I had to enter drill sergeant mode quite frequently, barking the students into a terrified submission. Often, I had to publicly shame certain students in front of the classroom just to make an example of them. Teaching was not an uplifting experience—for me or for the students.

For all those reasons, I had to quit being a substitute teacher. The person I feel that I am and the person I feel like I want to be did not line up with who I was becoming as a substitute. So I had to quit while I was ahead, before my integrity became corrupted by the corrosive classroom environment. I honestly enjoy working with children, but how did teaching become a position where children are viewed as the enemy? I’m not that kind of person. I don’t want to be that kind of person. But I am as much a product of my environment, and those toxic classrooms created a menace in me. I never wanted to yell at kids. I didn’t enter education to yell at children. But nevertheless I found myself slipping into the mire of the circumstances.

More than anything else, I was appalled by what I witnessed as the toxic learning environments that predominated in many school classrooms. It started with a culture of disrespect for the teacher and for the learning process, then broadened to include a disrespect for any students interested in learning. In my classrooms, there were numerous fights and countless episodes of crying. There were times where I as a teacher did not feel safe in the classroom. No doubt that my students, young and vulnerable as they are, felt any safer. Instead of becoming an opportunity for inquiry, learning became the punishment for misbehavior. How, then, can you expect anyone to value or invest in the educational process? Thus, I had to remove myself from the situation once I felt myself contributing to the culture of school as a penal system.

In stark contrast, life was much easier in the suburbs. I found I could be more relaxed and compassionate towards the students, reaching closer to my idealized vision of classroom flourishing. Instead of being a punisher and enforcer, I could be a friend, mentor, and teacher. But even though the suburbs are easier, I couldn’t allow myself to stay there. I could never feel right about selling out to the suburban school districts and contributing to the flight that attracts resources away from the already under-resourced districts. I felt it more important to be in the urban school districts where the behavioral issues were most pressing and the impact of a teacher is most needed. But I also found that I couldn’t survive there—at least, I found I couldn’t survive there while being the type of person I was striving to be. Being in the inner-city classroom for too long reverts one back to primitive survival instincts. Values like kindness and compassion take a backseat when your main goal becomes surviving the day.

The Inevitable Predictability of Career Tests

I’m a sucker for a good personality test. Still am, even as I get older and my personality seems to cement. I habitually take and re-take old favorites like Myers-Briggs, True Colors, or Enneagram just to see what my results are—generally, to see if they match the way I feel about myself. Retaking the tests as I mature, I’m always curious if my more recent results still match my results from earlier. Partly, this fascination stems from me always searching for new insights into myself—particularly, the kind of insights that feel certain and definite, like those garnered from the results of a scientific personality test.

My early college career was a particularly fruitful time for taking such tests. As an emerging adult trying to understand himself in a college context, such tests provided reassurance; they were like a friend who knew me well enough to point out that I’m not altogether crazy or odd. And with the personality tests came the related career-matching tests; young college me also needed to discern what role he would play in the adult world.

One test that stood out to me way back when and still stands out to me now was a career-matching test—the Strong Interest Inventory—taken at the career counseling center midway through my first semester. When I took this test, I was not looking for career matches in particular—I was still a stubbornly committed engineering major who was only taking the test as part of another class’s assignment. Given my doubts about the necessity of career counseling to begin with (I can figure everything out on my own, right?), offering the test as class credit was a great way to incentivize one reluctant college freshmen to venture into the career counseling office. However, upon having the test explained to me by the career counselors, I became intensely intrigued out of the sheer curiosity of what insights these tests might provide about myself.

The Strong Interest Inventory was not exactly just a career-matching test. Rather, it was a query of what I was good at and what activities I found fulfilling—and then the test metrics compared my results to the jobs in which people with similar aptitudes and interests described as fulfilling. Essentially this test was a comparison of how well my personality and interests would fit into a wide range of career fields.

A week later, after the results of the test were processed, I went back to career counseling to see the outcomes. As a college freshman blindingly intent on the engineering program, I wasn’t too happy with what I learned. Although already disappointed by the lack of joy that I was encountering as an engineering major, I was even more disappointed with the results of the career match survey. It wasn’t a surprise, then, that engineering was not in my top ten job matches. In fact, engineering scored rather low on the list, which gave some validity to the less-than-amorous feelings I’d been having to the engineering discipline. But—what I couldn’t get over was what my top career matches actually were.

Sitting there smack dab in my top ten matches were jobs I’d never even think of considering: chiropractor, corporate trainer, school counselor, nursing home administrator…on and on. Sure, I definitely could have seen myself as a carpenter. But match number two as a minister? (oddly enough, writing a blog post seems peculiarly similar to writing a sermon). And my top match…an elementary school teacher?!? What?!?!? Are you sure you didn’t mix my results up with someone else?

To my abundant surprise, my top ten career matches were vastly different than expected. As high school me had thought so strongly of his performance in the ‘hard’ disciplines of math and science (my stronger subjects in high school) and had greatly relished his introversion (i.e., I didn’t want a job working with people), he couldn’t have seen himself touching any of those occupations with a ten-foot pole. Opposite of my hard-science, asocial bias, my top ten matches were all very much centered on the social disciplines.

As a college freshman, I found the results so far removed from my expectations that they were amusing, borderline comical. I quickly dismissed the results and switched my major from engineering to…biology (to stay in the sciences, of course). I was not quite ready for such a radical switch from the picture I had of myself as an elitist physical scientist, nor did I believe I would desire such a socially-oriented job either. Sure, engineering was not for me, but even less could I envision myself in those other careers.

I tucked the results of that career-matching test away in a folder, somewhat out of personal respect at the mound of high-grade paper it was printed on, and partly out of the sheer curiosity of how wildly unexpected the results were. I mean, c’mon…nursing home administrator?

But reality found a way of having its last laugh on me. Though I shunned the outcome, I nevertheless kept making choices that wound me closer to the results of the test. My majors in biology and environmental studies deepened my love of nature, a passion that I couldn’t help but share with others. So I decided to begin working in the outdoors in a capacity where I could share this passion, first becoming an outdoor guide and then later teaching environmental education. After gaining some experience with youth in education, it wasn’t such a big leap to take on classroom substitute teaching when the circumstances called for filling in a gap in employment. That, of course, led to working in public schools—where the bulk of available assignments come at the elementary level. Thus, out of economic necessity more than sheer personal desire, I found myself working as my top career-match from that test of my freshman year. Inevitably, I have worked as an elementary school teacher.

And you know what? I agreed with the test results. Far from the discordance I felt earlier while in the engineering discipline, I found the elementary job to be meaningful and fulfilling. Being an elementary school teacher was a challenge that I could both accomplish and feel like I was making a positive difference in the world. Somehow the results of that career test snuck up on me. I’m glad they did. Left to my own devices, I wouldn’t even have begun to suspect that I would enjoy such a job.

Maybe there is a degree of validity to all these career tests that we take. After all, I didn’t go out in search of the types of jobs matched for me. Rather, one thing just led to another and I ended up stumbling to results myself.

(Perhaps maybe the results of another career-test will sneak up on me—during graduate school, I took a different career test that gave me the top occupations of nanny, combat soldier, gynecologist, and underwater welder. Of those, I’d take the underwater welder!)

Things Your Substitute Teacher Probably Never Told You

I’m not a certified teacher, nor do I have any training or classroom experience (but I won’t tell the the students this). The field is generally short-staffed, so any decently educated, mature adult can fit the bill. The work itself isn’t lucrative, and the pay isn’t too enticing either. Lots of us working this job are only doing it temporarily until something else comes along. And nothing irritates me quicker than having a student claim that I’m not a ‘real’ teacher.

I don’t know this school very well. In fact, I likely may have never been to this school before. So much of working this job is figuring things out on the fly—room locations, educational culture, school policies, etc.—and one of the best strategies is to find the nearby teachers who will be helpful throughout the day. In the classroom, much of the time I’m going to be relying on the students to ascertain whether I’m following classroom protocol correctly. And if I don’t do something exactly as your teacher does it—DEAL WITH IT!

I arrive at my assignment early enough to read over all the sub plans, always entering the classroom with a slight hint of dread upon the possibility that no material was left to teach in class. Though I may have read through all the plans ahead of time, I’m usually just a topic ahead of the class and I’ll use every spare moment to plan my next teaching move.

I often don’t know the material I’m teaching myself. I do know enough, however, to talk my way around things in order to give off the impression that I know. When I don’t know, I often ask for a student volunteer to do an example problem in front of the class—doing this might help jog my memory, but more importantly it makes the students feel more engaged in class.

I only have three sets of professional teaching clothes. I can get away with this because I’m usually never at the same school more than three days in a row.

I generally feel very appreciated by the school staff, even though often I don’t feel like I’ve done much in a day. I may not be a great teacher, but what’s more problematic for the school is having no responsible adults available to oversee the students. And at some schools, even making it through the entire day in the classroom is an accomplishment in itself.

My threats of punishment may very well just be empty. Since I don’t know enough about the punitive system at this school and where to send students for misbehavior, I often rely on the perception that a student will get punished as a method to gain cooperation. When I say I’ll leave names for the regular teacher about misbehavior, I make sure I do—but then I never know if the regular teacher ever does anything about it. When I do know where to send disruptive students, it is an incredible tool for classroom control. Sometimes all it takes to control a classroom is to remove one particularly disruptive student. At some schools, one of my initial tasks upon arrival is to learn how to call for security.

The teachers that the students fear most are often the teachers I fear as well. I’m not kidding when I tell the students that they don’t want Mrs. So-and-So to come into the classroom because she won’t be happy when she is forced to come in to chastise a deviant class. It’s not that I get scolded by the teacher for doing a bad job—it’s more like every time a teacher comes in to quiet my class, I feel like I’m not meeting the expectations of the substitute job.

I’m not just here to babysit. I’m here to teach, and I actually really love teaching too. Though much of my time is devoted to managing the behavior of the class, when I have a really engaged group of students, it makes up for the shortcomings of many bad days in a row.

I like it when students love me, but I think it’s often more fulfilling when they hate me. My goal isn’t to be the students’ friend, but if the students are mature, then I’ve found I can be more lenient as long as they are able to self-direct themselves to finish their work. If the students misbehave, though, I also like getting strict with them to the point where they clamor how their substitute is the worst one ever. When I hear that, I often feel accomplished for bringing some discipline to the classroom.

Sometimes I actually prefer the more difficult assignments. Sure, the suburbs can be nice and easy, and the kids can be very polite and well-behaved. But that gets really boring really quickly—those are more like the‘glorified babysitter’ assignments. At the other end of the spectrum are the really tough inner-city schools, where no one really ever has control of the classroom. I personally like the challenge of having a trying group of students with their myriad behavior issues, but only to the extent that their behavior is possible to be controlled. Not all days end up going well, and on those days where I fail I often get to learn more about how I could become a better substitute.

I also prefer working with younger grades—not necessarily because I enjoy younger students more, but because younger students need the teacher more. By the time students reach high school, they can pretty much take care of themselves. Younger students are often a squirrely handful, but I’d much rather have the day fly by with the many concerns young students bring to the teacher rather than spending the day being generally ignored by high schoolers.

I dislike showing videos in class. In fact, I often bemoan those assignments. Fortunately, I don’t show videos that often. Part of my dislike stems from having to watch the same video multiple times in a row—but more likely, I don’t like it because if the students aren’t interested in the topic, then making them watch a video leads to even more behavior issues difficult to control.

I can’t promise to remember everyone’s name. There’s only one of me, but there are 30 of you. And some of you may look similar to other students I’ve had before. I’ll try and pronounce you name right, but I’ve probably never heard of it before, nor will I understand how the letters in your name make certain sounds (like how ‘Aja’ is pronounced ‘Asia’). I feel bad for a lot of students based on their names—like the 7th grade girl named ‘Isis’. And with some names, like ‘Sir’ and ‘Everythang’, I have to hold back a chuckle while taking attendance.

Making the Memories You Will Love to Look Back Upon

Recently I took a trip down memory lane with a fellow co-conspirator of one of my most memorable spring break trips ever, a canoeing/backpacking trip to the wilds of Mississippi. It was a trip to be remembered not only because of the adventure but also because of so many things that frankly went haywire:

One of our cars breaking down on the first night in the country town of Effingham, Illinois; sleeping in our cars in the parking lot of the repair shop that first night waiting for the shop to open in the morning; taking a pilgrimage to the second-largest cross in America beside the freeway while waiting for said car to get repaired; running into a traffic jam at a police checkpoint on the highway late at night in muggy Mississippi—and having the power braking go out in the car during that episode; awaking our first morning in Mississippi to gunfire from local turkey hunters wandering through camp; canoeing down a river traversing from bank to bank the whole time because no one in the group actually knew how to canoe; nearly stepping on rattlesnakes sunning themselves on the trail—multiple times; having a deer run through camp at night and scare the living bejesus out of us; having one of our friends get bit by a water snake while we were bathing in the creek; visiting Alabama’s Dauphin Island on the last day of our trip and finding out there were no campgrounds to stay at—so instead after much searching, eventually knocking on a random parsonage door at night to ask if we could sleep in a parking lot (and instead getting invited to sleep in the church’s retreat center!); a fateful morning of napping on Dauphin Island’s beach, leading to second-degree sunburn and sun poisoning before driving through the night back to Michigan; stopping at a place called Hart’s Fried Chicken and ordering the greasiest things on the menu before the drive; washing all of our clothes at a friend’s house before the dorms re-opened, and then finding out that the dryer was broken; some friends finding ticks engorged in uncomfortable places after arriving back from the trip; it could go on…

Some might say that on this trip a lot of things went wrong. Personally I’m not apt to call these events wrong as such—more so, the events of the trip just went much differently from our idealized expectations of an uneventful vacation. Reflecting on the premises of the trip reveals that running into some snafus seemed likely. We were, after all, only a group of ten friends—sophomores in college—without any significant experience canoeing or traveling in the backcountry (and perhaps our resumes were lacking for road trip experience as well). But despite all the happenings and dangerous circumstances encountered, we all survived to tell the tale. We can look back fondly and humorously at the entire experience because no permanent harm was done (perhaps with the exception of guaranteeing ourselves skin cancer).

This trip to Mississippi stands out from other trips I’ve taken particularly because of the number of things that went unexpected. Looking back, the whole trip could have been written as a comedy sketch. How many goofy things could possibly happen in this episode of college wilderness spring break? On trips I would take in the future, I would apply the lessons I learned from past mistakes. I would gradually get more comfortable in the outdoors, make better trip preparations, and foresee adverse situations before they would arise. Things got a lot easier with more experience. But I also found they got less memorable.

The following spring break was also a canoeing trip with friends, this time on Florida’s Suwanee River. The entire trip went off without a hitch. No car trouble, no inadequate provisioning, no half-baked plans. It really was a trip you could wrap up neatly and put down in the books. But I felt a little shortchanged from it. I felt like I got off that trip a little too easy. Somehow, I felt like I had been gipped. Thinking about the Suwanee trip years later, many fine details of the experience are largely forgotten, and few stories about it have been re-told. The trip itself does not possess much salience in my mind either.

I think this example of these two spring break trips illustrates a trend I’ve noticed in my life. As someone who learns quickly from past experience, I don’t possess anywhere near the level of greenness or naïveté I had in my early college days. I’m now able to get through life easier without committing so many of the egregious errors or faux pas of my younger years. As I get better at navigating the messy world of life, I’ve noticed one unintended consequence: I’ve been making these distinct memories of unexpected circumstances with far less frequency.

I’m aware of this trend, and part of myself is frightened that I’ll stop making memories quite as spectacular as my Mississippi spring break. I’m concerned that life will become mundane and routine, and the vivid experiences of life will slip into the hum-drum milieu of quotidian tedium. I’m afraid that I’ll no longer be making the memories which I’d love to look back upon. Psychological research details how our lives mellow out as we age. I was a mellow personality to begin with, and I’ve already seen myself soften out more as I’ve gotten older. As I mature further and gain more life experience, am I going to find it increasingly difficult to make specific memories? Am I going to run out of things to try that are absurdly outside of my range of expertise—or will I even lose the motivation to try such things?

I wonder if this fear is one of the reasons why I’m wary of settling down, why I keep flirting with transiency and playing hard-to-get with consistency. That instead of doing one thing in one place for a long time, I keep wandering from place to place and from job to job seeking out new places and experiences. I’m no longer absurdly incompetent in a lot of areas as I once was. Years later, I have become very proficient in outdoor travel. I’ve even worked as a canoe guide. If I were to take it again now, a trip like my Mississippi spring break would likely present little challenge to me.

Instead, I find myself seeking out new areas in which I will continually challenge my limits, branching out into more and more disciplines. Once I felt comfortable with my level of mastery at the things that interested me most, I had to start seeking positions further afield where I could step yet again outside of my comfort zone. True, part of my motivation for doing this is the desire to develop new skills in other disciplines. But I am also motivated by the challenge of doing things that I’m not familiar with and the memorable experiences that ensue.

And this process of doing things outside of my comfort zone, I’ve found, is a key element in adding to the memory-making process. It’s something I can control that augments the production of memories. Truly, my working holiday in Australia was partly motivated by this, especially by a desire to break from the monotony of going to grad school day after day and living a stable life in the same house for two years in a row. The scope of my Australian journey was a stretch for me, and how it comically unraveled produced many great stories and memories about how naïve and unprepared I actually was. But—I learned so much from that experience that if I were to do it again, it would be far easier for me—and also much less memorable.

I still find myself drawn to employment positions that are slightly out of my comfort zone and realm of experience as well. In fact, it seems to be a job requirement for me. Substitute teaching in public schools has been a great example of this. I was incredibly nervous before I started subbing, and I still often feel out of my element in the classroom. But I have accumulated a treasure-trove of memories and stories from the experience (although my most vivid memories are of just how awful children can act). Though far from a professional, even after just a few weeks of subbing I’m beginning to feel more comfortable leading a classroom. I wonder if that’s a sign it’s time to try something new?

Am I drawn to the memories? Am I addicted to them? Am I drawn to novelty and repelled by familiarity because I covet the memories that novelty so often provides? Am I scared that based on the trends I’ve seen so far, that I’ll eventually run out of things to do in order to make new memories? Is my incestuous desire for vivid memories stifling my development?

I want to keep making new memories, though, and memories that will stick around with distinction. The question may be how to go about this. How can I still make new memories and lead a more stable and consistent life? Somehow I need to find a way of continuing to make mistakes worth learning from. As long as I survive those mistakes, I’ll be able to look back on those memories fondly.

A Day for Love and Cuttles

There ought to be one day of the year set aside specifically for love. It should be a celebration of all which you hold close to you. How about February 14th as a celebration? It’s a pretty ordinary day otherwise, and a pretty bland date coming in the middle of a late winter month as it does. I think today would be the perfect candidate for a special holiday.

In addition to celebrating the things you love today, why not also focus the day on cuddling—or, perhaps it’s more like cuttling? If you haven’t picked up on my point yet, I’m writing about none other than the cuttlefish. By far my favorite marine cephalopod. And why not? Just take a look at those big puppy-dog eyes and that tentacled smile waiting to embrace you in a kiss.

I thought about all this last February 14th too. On this day last year, I took a long sunset stroll down the white-sand beaches of Australia’s Bribie Island. In the fragrant subtropical air and the warm, salty ocean breeze, I found my love—or at least their remains. Along the beach were washed up several large cuttlebones—the hard remains of these invertebrate animals that give the cuttlefish both its internal structure and its buoyancy control. Like a lover’s distinctive gaze, the cuttlebone is the distinguishing feature of the cuttlefish, separating them from all other classes of cephalopods. But don’t take the name ‘-bone’ literally—the cuttlebone is extremely porous and composed of the mineral aragonite, unlike our own calcium phosphate skeleton. Maybe you’ve even handled a cuttlebone yourself, if you’ve ever fed one to a pet bird or reptile as a good source of crunchy calcium.

Before my long walk on the beach that night, I had a romantic dinner with my cuttlefish love; the cuttlefish showed up for the main course. Worldwide, many people enjoy dinner with a cuttlefish regularly. Especially in coastal areas of Europe and East Asia where the cuttlefish inhabit the waters, cuttlefish appears frequently on the menu. One typical Italian dish, risotto al nero di sepia, marries Arborio rice with cuttlefish ink.

I try to see my love frequently, not exclusively on February 14th. At every aquarium I visit, I instinctively zero in on the cuttlefish exhibits. Watching both their sleek movements and awkward bumbling can make anyone’s day. Cuttlefish can rapidly blend into their surroundings by changing the colors, patterns, and textures of their skin, which helps them both hide from predators and ambush prey. Their camouflage can even form moving patterns along the body, like nature’s organic jumbo-tron television.

Hearts are a rather appropriate metaphor for love, especially for the cuttlefish. With one heart for each gill and another for the rest of the body, cuttlefish max out at three hearts—that’s a lot of love to give. And these bleeding hearts don’t turn red; cuttlefish blood is a distinct blue-green hue due to the copper-containing molecule haemocyanin that transports oxygenated blood rather than the deeply-red colored haemoglobin found in vertebrates.

Gaze deeply into your lover’s eyes as well. Such a graceful W-shaped pupil, so deeply black and yet so alien. Any resemblance to our own eyes is a superficial product of convergent evolution. The cuttlefish can see things in us that we can’t see in ourselves; though their eyes cannot detect color, they can sense the polarization of light. And unlike our own flawed perceptions, these creatures don’t have blind spots.

A love for cuttlefish isn’t complete without cuttlefish love either. In their relationships, cuttlefish are excellent communicators, changing their colors to reflect their moods and intentions. A male cuttlefish can tell if a female cuttlefish is ‘interested’ if she turns the aptly-named ‘precopulatory grey’ pattern. But cuttlefish romance is also full of intrigue and deception. Non-dominant males can change color to pose as a breeding female. They can then sneak into the territory of a larger competitive male and surreptitiously mate with females. Cuttlefish romance sounds like the makings of a terrible aquatic soap opera!

The preferred copulatory position is face-to-face. The male cuttlefish will grab ahold of the female with his tentacles, and then use his extra pair of tentacles to insert his sperm sacs into an opening near the female’s mouth. The male holds onto this lovers’ embrace until the female lays her eggs a few hours later.

It’s tough for a male cuttlefish to find love out there. Typical cuttlefish populations have up to 5 times as many males as there are females. The playing field is jam-packed. If a male loses his female, there just as well might not be more fish in the sea (actually, cuttlefish aren’t fish but are mollusks. They are more closely related to snails than vertebrate fishes). If all chances of love fail nevertheless, a cuttlefish can still try their luck with brains. These animals have one of the largest brain-to-body size ratios in the animal kingdom.

Finally, any romantic holiday should include a fancy dinner. Seafood is a wonderful idea. The cuttlefish love to dine on shrimp, crabs, and fish. Their table manners could use work, though. They grab ahold of their prey by sneaking out their two feeding tentacles then snatching their prey at rapid speed, shocking their victim in the sneak attack. The hapless prey is then brought into the folds of the cuttlefish’s tentacled mouth, where it is paralyzed into submission with a toxic venom. Though they may gnaw on their entire meal whole, at least they don’t have bad enough manners to chew with their mouths open.

Is it Lame to Join a Book Club?

“Many people, myself among them, feel better at the mere sight of a book”

—Jane Smiley

An existential question of our modern culture: is it lame to want to join a book club?

The desire about joining seems too old-fashioned. Book clubs are akin to knitting circles—full of graying genteel grandmothers politely gossiping (or at least that’s the perception). Who in their right mind would find interest in such a stodgy old meeting merely to discuss books? Especially in your 20’s when you’re supposed to be young, wild, and free? How lame! Bookworm!

Still, the thought of a book club holds great appeal to me. Admittedly, I am bookish. I spend a great deal of my free time reading. After college, I found that I greatly missed the intellectual discussions surrounding books and ideas. Aren’t college classes, in some sense, a kind of book club?

Maybe in fact I am the perfect candidate for a book club. My appetite for intellectual stimulation is tremendous. It’s a need to satisfy that I just can’t scratch in other ways. My mind needs the mental exercise, and it’s much better when the workout is shared.

But it’s not just the intellectual part I am drawn to…

Back in Australia, when I was living out of a van and driving around on a quest for fruit, I happened to overhear a news program on the radio that caught my attention. The news story was about a wave of young people joining book clubs. Contrary to my perceived notions that book clubs are for elderly women discussing harlequin romance, this radio piece detailed how a growing number of millennials are joining book clubs for both the intellectual stimulation and social comradery.

Me, driving aimlessly around a continent, had an epiphany: a book club is exactly what I’m looking for.

Well, not a book club specifically, but it does perhaps provide the best example.

For, it was not just the intellectual discussions inherent in book clubs that I’d been craving during my ramblings. Equally, it was the social aspect to the club. To have a group of friends who are interested in that kind of thing? How awesome! How radical to commit to doing something noticeably unhip like reading and discussing a book with a group of people. And what’s more, to follow through with the commitment. And then to keep following through…

Because joining a book club is not a one-off fix. It’s not solely just reading one book with a group of people to satisfy a craving. Fundamentally, it’s the longer-term idea of being part of a group through the long-haul. Through both the ups and the downs, through the Moby Dicks and the Twilights.

This need for belonging doesn’t have to occur solely through book clubs either. Fulfillment could be found in many places, like a service club, a volunteer organization, or sports in the park. For me, the point is to be committed to something greater than myself. Arguably, a book club might not be too much greater than yourself, but it is particularly symbolic of making a commitment to a group of people and then following through with it.

And what transient can dare make a commitment to something as far-reaching as a book club? Here today, gone tomorrow. Never in one place long enough to finish a good read. It’s the notion of committing to a club, that idea of rootedness, where the bulk of the appeal lies. Personally, I find it unfortunate that I seldom stay in one place long enough to make it through one book, let alone sustain a book club.

So is it lame to want to join a book club? Not in my book.