The City and the Ship

The Clearwater approaches her dock in Manhattan

The sloop Clearwater has a berth in New York City, 79th street on the west side of Manhattan. This is the southernmost dock for the sloop, and the most urbanized. While the ship’s surroundings can change drastically at different ports, daily life on the boat remains much the same.

The 79th Street Boat Basin sits beside a long stretch of parkland in the city, a thin insulating strip of green that buffers the recreational waterfront from the tumult of the city. Access into the city is by crossing through the open air Boat Basin Café onto the terminus of 79th street. Going through the arches of the café is like stepping into a rabbit hole; an entirely different world exists onshore.

A few blocks away from the docks runs Broadway. In the residential Upper West Side, the street is well trafficked but lacks the frenetic aura it is caricatured for. Continue along Broadway until it begins its southeast turn; the buildings soon become larger and more commercial. A few miles further on lies Times Square. At the heart of the city, the hustle and bustle grows to its climax here. Flashing lights and monumental billboards scream for your attention. The pace of life seems to quicken, and you can almost feel the chaotic energy of the square seeping into your veins. The metabolism of the city is high. It’s calling you to see and do and consume.

The big city is fun and exciting. There is lots to see and experience. Somewhere, at all hours, something is going on in the city that never sleeps. A diversity of people walk the street. New sights and sounds lurk around every corner. The smell of exotic foods wafts from street vendors. A lifetime of exploring could never discover all the corners of such a metropolis.

Times Square at night

I find the city lively and exciting. Its abundant stimuli rouses the mind. But I can easily get overwhelmed by the city.

I prefer the simple life instead. The boat, though basic, is homely and comforting. The bounds of the ship are fathomable to an overworked mind, and the intricate corners and inner workings are knowable with time and care. The 76 foot length of deck serves as the bounds of my home, one that I share with 18 others. Down below deck, 36 cubic feet of space is all that I can claim as my own, which serves as my bed and storage space by night, but doubles as a couch during the day. Inside the ship, the spontaneous whims of the city don’t find their folly. Instead, a set schedule adds structure and predictability to daily life. Life onboard is a ritual of sorts.

It is a lifestyle of simplicity, not excess or extravagance. On the Clearwater there are no fancy restaurants or fine dining. Vegetarian meals are shared with the crew, who gather together to eat in the cozy main cabin, sitting on the floor or perching on bunks to make room. The fare, whole and nutritious, sustains the body after a day of labor. No fancy dress or designer clothing are required onboard. The dress code is one of practicality and pragmatism. Most of the crew onboard have just a few articles of clothing, second-hand flannel shirts and thread-bare workwear. The grassroots vibe emanates still from the earliest days of Clearwater. Crew all contribute their part to the internal functioning of the ship. Daily chores and tasks are shared among shipmates in this communal setting.

Far fewer people live on the boat than in the city. But instead of a metropolis full of people whom you never get to meet, the boat is full of people you quickly get to know. Working closely during the day transitions to hanging out later at night. We play music together, and share in conversational rabbit trails. Daily life on the boat is an exercise in communal bonding of the sort that gets a boat to run and sustains an idea of environmental activism.

On a night at 79th Street I can crawl up on deck from below. The lights of the big city surround me. Red and white glowing orbs from traffic continually roll past and the noise of urbanity lingers still. Looking up I can see the lighted spire of the Empire State building and I know that I’m in the heart of America’s most densely populated city. But things are calm and quiet on the sloop upon the Hudson.

I much prefer my little ship in Manhattan.

Learning the Ropes

The sloop Clearwater sailing through the Highlands section of the Hudson River

“It is not that life ashore is distasteful to me. But life at sea is better.” –Francis Drake

I’ve been learning the ropes lately, so to speak.

It’s been two weeks on the Hudson River Sloop Clearwater, in a crash course on boatsmanship and environmental education. I’m a sailor now, though I’m not yet as salty as my boots are from swabbing the deck with brine.

Foremost, learning the ropes entails that a rope isn’t just a rope—it can be a line, a sheet, a halyard or a downhaul. The nominal difference doesn’t mean much to a landlubber’s hands, though—every rope helps aid in developing the all-important sailor callus. Two weeks in and I can now flop-flake a downhaul, dogbone a line, or Ballantine a halyard. Better yet, I know what all those terms mean too. But learning the ropes goes beyond just the ropes—among other things I’ve learned how to hoist up the main sail, steer with the tiller, be a dock jumper, and furl the jib.

Confused by any of the terms yet? Sailing culture has its own lingo. Rarely does a component of a boat share its name with its onshore counterpart. The cook prepares food in a galley, not a kitchen. Below deck, we walk upon the sole instead of floors. And, using the head on a ship is an entirely different thing than using your head on land. By now, practical experience has resolved my long-standing confusion of which side of the boat is port and which is starboard. There are so many new and funny-sounding terms to learn: jib, gaff, shroud, boom, peak, throat, transom, fo’c’s’le, dogged, pin, cleat, lazy jack, and my favorite new term baggywrinkle. Though we may be on a tall-masted historic ship, we aren’t pirates. No arrrghs or ahoy mateys found here.

The 106-foot long Clearwater under full sail

The Clearwater is very much an educational ship. Its revolving crew of apprentices, interns, and volunteers, who stay for one week to a few months, means that new hands are always coming aboard to learn the ropes for themselves. This means that onboard the ship is an active learning environment; new crew learn from their shipmates, and those aboard for longer gradually switch from primarily learning to teaching as well. Two weeks in and I’m happy that I can now ‘show the ropes’ to newcomers. The constant influx of trainees and volunteers serves as an indicator of the grassroots origins of the Clearwater, which was founded by Pete Seeger and other activist musicians in the late 1960’s to educate and create awareness about issues of water quality. Clearwater’s alumni crew number many and all contribute their part to the mission of the ship in a different way.

New crew members get one full day of formal training before taking part in educational sails. The rest of learning on the Clearwater is done practically—learning by doing. The process of sailing itself proves to be very educational, and with around 20 sails now under my belt, I’m beginning to feel quite comfortable at the undertakings. Tasks onboard are done in a progression of difficulty. Prove yourself capable of performing one task, and the captain or mate will assign you to something more challenging. Each day and each sail is a little bit different, so there’s always something new to learn. Standing by as a deckhand, you never know which task the mate will assign you to—and once you’re told, you just have to repeat back the command and perform the task with minimal preparation. Learning by doing on such a large sailing vessel seems like a high-stakes game, but everyone’s looking out for each other to make sure the crew is learning well and performing their best.

Education aboard the Clearwater extends from training the crew to instructing the participants on the ship’s many educational sails. The primary focus of Clearwater is the educational sails, and a typical day sees two three-hour sails of this type take place. All of the crew onboard are not only sailors but are also educators, and will lead a variety of educational curricula. Students who sail are as young as fourth graders and as old as college students. Just like every sailing condition is different, every educational program is tailored to the needs and learning level of the group. The basics of each educational sail remain the same, with participants helping to hoist the sails before going to different learning stations covering aquatic life, water quality, Hudson River history, and navigation. As someone not from the Hudson River watershed who knew little about the river before sailing, I’ve ended up learning as much about the Hudson River as the students I teach. At first, teaching the standard material is being only one step ahead of the group in knowledge. After a number of sails, though, I’ve found I’ve learned enough to teach more and more, and every new sail presents an opportunity to teach the same material in a different manner. And, I absolutely love it when people ask me a question that I’ve just learned the answer to.

Learning the ropes also means adjusting to a different lifestyle. A life on the river is different than a life on land, particularly when you live on a replica of an 18th century cargo ship. The modern conveniences of life aren’t found in the living quarters. There is no air-conditioning or heating, no refrigeration, and only limited electricity and running water. Our restroom situation is as simple as using a five-gallon bucket. Living on the ship really shows you how much—or how little—it actually takes to live. The social environment is an adjustment too. With a crew of up to 19, quarters are close on the 76 feet of Clearwater’s deck. You have to be comfortable not only working closely with people, but also living with them on your time off. However, the Clearwater tends to attract a certain type of person who can thrive in a tight community aboard an active sailing ship. The community onboard the ship has been the best resource for learning to sail and one of the biggest highlights of learning the ropes.

Learn more about the sloop Clearwater at http://www.clearwater.org

1,234.63 Miles Later

Stopping in Chicago along the way

My bicycle hobbled over the pavement for the final stretch, rims wobbling, bearings creaking at every turn. One thousand miles of loaded travel puts a great deal of wear on a bicycle. Tires bald, brakes worn down, dozens of new scratches in the bright yellow paint. I rode with baited breath my final day, hoping that my emergency tube patch job would hold after blowing my last spare on a particularly aggressive Indiana pothole the night before. Braking for the last time on my parent’s uphill driveway, I came to my final stop. 19 days. 1,234.63 miles.

It was a rather uneventful end for such a long trip. Arriving at my destination felt no more different than returning from a short evening ride. The cheering spectators, the paparazzi that I’d expected were absent. I had thought that my trip would deserve an epic fanfare, a grandiose welcome after such a long physical exertion. What I got instead was a simple welcome home from my parents. Soon enough thoughts of riding drifted away from my mind as I integrated myself into my parent’s nightly television routine. Coming back from three weeks of biking felt little different that coming back from a day at the office

I ended up cutting my trip short by a day. Camping in Indiana on what would be my final night, I made the decision to push through and make it all the way to my destination instead. To myself I had already proven my capability to endure the journey; all I needed to do was complete the trip. Instead of leisure and sightseeing on my final day, I just put my head down and rode. Peddle after peddle, mile after mile kept adding up until I amassed 113 in one day. With goal in site, no time to relax—just time to ride.

The most intense feeling I had on my final push was one of relief. Biking north out of Michigan City, I caught glance of the giant blue “Welcome to Pure Michigan” road sign. After so long away, finally back in my home state. A lump grew in my throat and my eyes teared up as I crossed the state border.

Overcome by sentiment at reaching the state line

Later on, coming into the outskirts of Holland, that same emotional relief came over me; ‘I recognize this place now’, I thought to myself, ‘I know where I am. From here it’s only 4 miles, 3 miles, 2 miles…’ To the onlookers curious at why the overburdened cyclist was sobbing, there is only one simple response:

I had made it

What difference does it make now that such an arduous trek is behind me? Already the memories of the toil are fading. The afterglow was short-lived. A few hours after arrival I found myself showered, rested, and unpacked from the journey. No time to bask in remembrance, and only a few people to recount the adventure for. Instead I had pressing work to prepare for my upcoming job.

But already I feel nostalgia for the journey. The lactic acid has since drained from my legs and I’ve forgotten how sore I felt on the expedition. Rosy retrospection smiles kindly upon the difficulties, and I find myself yearning for more. A journey of one thousand miles, and I had chosen to stop in the middle of America when more road lay yet before me.

After such a long journey, after such a feeling of relief when I finally made my destination and could rest, I realized one thing:

I could have still kept biking on.

View from the Saddle

Fast enough to get places, but slow enough to see them–that’s what I enjoy so much about travel by bicycle. The saddle may not be comfortable, but the views provide the reward. Traveling over 800 miles in 11 days has heightened my geographical senses. Slowly peddling a great distance, one gets to play landscape detective: what’s changing and why?

Guerrilla camping in the majestic white pine forests of northern Wisconsin

The northern hardwood forests began to become infiltrated by beech and maple, warmer clime species from more fertile soils found further south. Farm country spontaneously erupted from the sylvan wilderness. Along the lakeshore, farmland eventually gave way to industrial cities.

The landscape shifts imperceptibly, but gradually, determinants of the physical and cultural environment. Any given day I could find myself peddling down a rural country road or meandering on a dirt track through a mature forest.

Traveling through a forested corridor along the Eagle River Trail in northern Wisconsin

Following the route of the railroad on one of Wisconsin’s many rail-to-trail paths, the Glacial Drumlin State Trail linking Milwaukee to Madison

The weather changes also, with it bringing different moods to the landscape. Bright sunny days can make the terrain warm and inviting; cool, cloudy days present a somber melancholy air. Staying alert to the changing light environment rewards the onlooker with a multiplicity of panoramas, an ever-evolving sensory scene.

A diversity of clouds fill the sky above Green Bay

The rainbow after the storm: rural Wisconsin after a thunder shower passes

The culture shifts along with the landscape it inhabits. Forest land gives way to farm country. Tourist towns and sleepy hamlets lie tucked under the lakeside bluffs on the Door County Peninsula. Large industrial cities occupy important harbors on the Michigan lakeshore. Out in the hinterlands, a lone water tower on the horizon signals an approaching town.

Riding the Mariners Trail into industrial Manitowoc, Wisconsin

Along the way I pass through areas of local history and interest. Where did the inhabitants of Oostburg come from? Why is there a village of Wales in the Wisconsin countryside? Roadside markers provide insight on the history of each small settlement. By car, it’s an inconvenience to stop and learn; by bike, it’s a welcome break from pedaling. Roadside harvest stalls showcase the seasonal agriculture and nourish the famished biker. A destination of interest, no matter how modest, is worth stopping along the way.

The spiral staircase leading up the Cana Island Lighthouse in Door County

View from the top: Potawatomi State Park’s 75-foot tall observation tower

Beautiful nature abounds if you go out and seek it. Along the tracks and trails, nature displays her splendor. These places call out, beckon you to come close and linger.

Dolomitic Limestone formations at Cave Point County Park, Door County

Stopping for a swim break along a sandy Lake Michigan beach–Point Park State Forest

The long journey is never about reaching the destination; it is about the process of discovery along the way.

The (Bicycle) Journey of 1,000 Miles

Ready to go at the starting point

p

“Nothing compares to the simple pleasure of riding a bike” John F. Kennedy

p

Confucius may have wisely remarked that a journey of a thousand miles begins with a single step, but since the bicycle wasn’t invented until 2,000 years after his time, he never got to say that the bicycle journey of one thousand miles begins with a single pedal. Also dealing with one-thousand mile journeys, another hero of mine, John Muir, began his period of long wanderings as a 20-something with a 1,000 mile walk from Indiana to the Gulf Coast. So it only seemed fitting that I should embark on a thousand-mile journey myself—1,000 miles of adventure and exploration via the bicycle.

I could write on and on about how my upcoming bike ride is a promotion of bikeable communities and alternative forms of transportation. I could posit this venture as a political statement about our oil-dependent and vehicle-oriented transportation system. I could say I’m doing this ride for all the health benefits of biking. I could even pass this journey off as a slower-paced trip along the backroads of rural America, where I can see my own country in a new light and get to meet authentic everyday Americans.

But really, I’m going on this journey because I really like to ride my bicycle. Well, and that I don’t have a car—or enough money to justify a plane ticket for that matter. And somehow I need to get back to my hometown from my summer camp job in rural northern Wisconsin.

The idea of biking back home after camp had always been at the back of my mind, even before arriving at my summer job. That’s the reason why I made sure to ship my bike to Wisconsin and only arranged for a one-way ticket to camp. Having nothing lined up after camp (well, initially, that is!), I found myself in the predicament where I had ample time to travel, no hurry to be anywhere, little money for gas, and a great desire to really travel. What better to fit my circumstances than a bike trip.

I have frequently entertained the idea of a long trek by bicycle, but have never yet risen to the occasion. Sure, I am the veteran of a handful of overnight bike camping trips, and in the summer of 2011 I completed a three day/two night bike ride of 200 miles in New England. But the really long journeys have remained little more than fantasy for me. I have select group of friends who I routinely discuss long bicycle adventures with—be they cycles across America or a bicycle trek of Europe. Will a successful regional gig be a testing of the pavement for something greater down the line…?

On this journey I will be traveling with my constant companion, noble steed, and packhorse, my (still unnamed) bicycle. Me and my bright yellow bike have been together since 2010, and she’s a 1990’s model Cannondale that I bought second-hand. She’s not a fancy bike or an expensive bike, but she’s a sturdy bike who can carry a load and take a beating. Weighing in at 36 pounds with accessories, she’s an-aluminum frame touring bike with all the features. Fitted out with my load of camping supplies, clothes, rations, entertainment, and other odds and ends I wanted to bring, the total weight of my outfit rises to 78 pounds. I could have packed much lighter, but then again extra weight on a bicycle isn’t noticed too much.

Gearing up for the trip with everything I’m bringing with me

On average I’ll be riding between 50 and 60 miles per day. From start to finish I’ll take 20 days, with a few layover days scattered throughout for rest and recreation. Although I haven’t done as much training for my ride as I hoped, I feel more than ready. Long-distance biking is a challenge of endurance, not strength. So much of endurance is the mental resolve to continue.

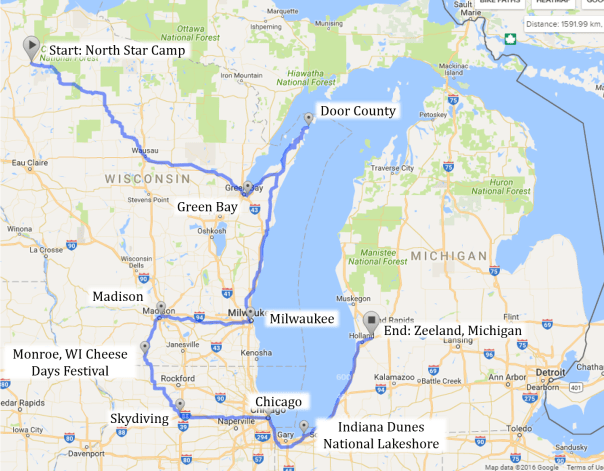

If the point of the journey was just to get myself back home, I could do it in under 500 miles (although that would necessitate a ferry across Lake Michigan). But I’m taking a meandering route, stopping by some special places and enhancing the trip by visiting friends, which increases my projected distance to over 1,100 miles. I’ll try and post regular updates as I go along, but here is a general overview of my itinerary:

September 3: Leave North Star Camp and start my bicycle journey

September 8-9: Biking tour of Wisconsin’s Door County peninsula

September 10: Day in Green Bay

September 12: Arrive in Milwaukee

September 14: Arrive in Madison

September 16-17: Cheese Days Festival in Monroe, Wisconsin

September 18: Skydiving outside of Chicago

September 19: Arrive in Chicago

September 20: Indiana Dunes National Lakeshore

September 22: Arrive at parent’s house in Michigan

(September 24: fly to New York to start next adventure as crew on the Sloop Clearwater)

The Future Leaders of the World

On the road to North Star Camp for Boys, one passes a somewhat whimsical sign in the shape of a yellow caution diamond: CAUTION: Future World and Local Leaders at Work and Play.

Though I find the sign amusing, I also understand the truth behind it. The campers who attend North Star are, indeed, likely to become leaders of their communities and beyond. North Star is not a representative sample of children nationwide, and though these campers come from privileged backgrounds, they also face high pressure to lead and succeed. Families of North Star campers care enough about their children’s development to send them to an 8-week residential camp, and also have the means to afford it. Hailing from these types of environments, the campers at North Star tend to be more precocious and generally well-behaved—future leaders in training.

But, right now they are still kids. They aren’t fully aware of the significance of their background or how that affects their behaviors or expectations for the future. However, someday, like each successive generation has before, these kids will grow up and realize that it is now up to them to run the society they want to live in.

Whether or not we raise children of our own, we still all share in the same future of the world, and we all ought to share in that responsibility of raising the next generation. At age 26, having children of my own is a distant speculation—but though I don’t feel the evolutionary impulse to pass on my own DNA, I nonetheless feel the societal impulse to raise and nurture. Regardless of whether I procreate, I still have a future in the world to come: I still have that collective responsibility to invest in the future of humanity.

Maybe working with children shows that you are an optimist about the world. In a time of global turmoil, with pressing political, social, and environmental problems, you’ve got to have faith that the world is going to continue in order to devote time to the youth. If there is going to be no future, then why invest in the next generation at all? For me, I still have faith in social progress, that my generation can resolve some of the issues unresolved by earlier generations, and that the generation after will continue with the work left undone by mine.

My own generation—the millennials—is still up-and-coming. We have not risen to prominence yet. Nevertheless we are beginning to see the ways that we can lead and are learning about the power of our collective choice. But we are still learning. We still need the guidance from generations before, seeking advice from parents and getting mentored by those older and wiser than us. In a similar way, we’re already influencing the generation under us.

I’m not sure if the campers at North Star are part of the same generation as me. Even the oldest campers I’m more than a decade senior. These are kids whose entire lives exist only after the year 2000. Though I can relate to them in many ways, the world they are native to is ever so slightly different than the one I grew up in.

For as much as I may paint a picture of working with kids as some deeply-contrived social obligation, I don’t do it for any external philosophical reason. I do it because I have found that I enjoy working with children.

As someone who commonly feels socially awkward amongst peers, it has been energizing to work with children. Just because you are bigger and older, children give you a lot of undue credit right from the start. They look up to adults who want to spend time with them. They find you interesting as a person, and because of that they become attentive for what you have to teach. To a kid, the world beyond their parent’s home is a vast unexplored horizon. Already I’ve done many things with my life that kids find interesting to hear about; I can regale them with stories from the other side of adolescence, about adventure and exploration, about amazing things from this world. Sharing things that have become mundane and commonplace to me could be the first experience a child has with it—and that exuberance a child has when experiencing something for the first time is ever-encouraging.

The youth of today are the leaders of tomorrow. But it’s not just for the campers at North Star—it’s children everywhere who are the future.

Confessions of a Trip Leader

The crew of the first trip I ever guided–a nine-day trip to Ontario’s Quetico wilderness

Getting paid to do what you love for a profession—an idea very appealing to a young, idealistic adventurer. We all have to work to earn a living anyway; might as well find a way to get paid for our passions. For myself, I really enjoy spending time in the outdoors, visiting wild places and traveling in the backcountry. Even if I held a conventional job I’d be doing these activities in my own free time. So, with an ample demand for outdoor guides in the recreation industry, why not become a guide and get paid to do my favorite pastime? Plus I’ve always enjoyed outdoor trips more when I’m with people to share it. Thus working as an outdoor guide seemed like an ideal position for me: I’d not only get to take people to spectacular places in the outdoors, I’d earn a livelihood from it as well.

I had entertained the fantasy of being an outdoor guide for a long time coming, basically ever since I went on my first guided trips and learned that guiding can be a profession. The outdoor guides leading me had always seemed to carry a certain aura to them: super-engaging, energetic, and adventurous. They got to spend so much of their time going out on trips or hanging out and goofing off at the outfitters. I perceived them as experienced gurus capable of surviving outdoors under any situation. They also seemed timeless—living eternally in the carefree moment of the trip and not caring about what happened before or what would come after a trip. Most important of all, they all seemed to be having fun no matter what. This was my preconceived notion of who outdoor guides were.

Now I’ve completed my first experience on the other side. Technically I have been a professional guide, since I received compensation for my guiding services. Yet it still feels really out of place and especially undeserved to consider myself a professional. I still feel like such an amateur, and so many of the skills required for the job I’m still developing. But as I’ve seen from employment, aside from the rudimentary outdoor skills needed to run a trip, a guide doesn’t need to be a technical gearhead at all. In my case at North Star Camp, I wasn’t hired for my technical skills—I was hired for my judgement and ability to relate to children. My guiding job was a whole lot more social than I expected; and perceptive social skills more so than advanced technical skills really make each outdoor trip memorable.

North Star Camp took the kind of people they wanted to hire and made guides out of them. Most trip leaders at North Star, like me, had very little canoeing experience prior to the summer; some had never even canoed before. But we all learned quickly. So many of the requisite technical skills of guiding can be trained in a short period of time. In my case, this included basic wilderness medical safety gained in an eight-day Wilderness First Responder Course followed by an intensive two week trip leader training conducted by North Star. All the trip leaders at North Star Camp this summer were first-time guides; our training consisted of an abundance of practical practice as we essentially scouted all of the trips we would be taking the campers out on. By the time the first campers had arrived for the summer, I had undergone nearly a month of training. By then I was more than ready to start guiding people. Adding campers to each trip just seemed like the next logical step—not much of a stretch at all.

However quickly technical outdoor skills can be taught, the parts of guiding that are most difficult to train are the interpersonal skills and social perceptiveness needed to effectively lead a group through the wilderness. The social aspect of the job can be touched upon during training, but so much of it is developing your own guiding personality from experiences gained on the job. Being an outdoor guide is quite like a big game of improv, a constant flux of evaluating the conditions and then adjusting plans based on a reading of group dynamics. Should we break for lunch here or there, now or later? Should we get to camp early or sleep in late? Does the group want free time or more structured activities? Aside from the generalized structure of a trip which details major trip checkpoints, a lot of events on the trip are still unknown even to the guide. Most of the time we’re just one step ahead of the group with our decisions, but we pretend we had an exact plan in mind the entire time. So much of guiding is just acting the part, looking confident and making decisions on the fly. Constantly we keep weighing multiple scenarios in our heads, evaluating which ones would benefit the group the most based on continually changing circumstances. Although before each trip goes out there is a lot of prep work in order to be adequately prepared, once you’re out in the field there’s a limited amount of control over the circumstances—everything else is just improvisation and making do with the conditions.

So much of being a guide is acting the part

Being an outdoor guide may have been the most fun job I’ve ever taken, but still it’s a job. Getting paid to take vacation after vacation is not the right idea for it. Sure, I’d be inclined to take personal outings to the places I led trips this summer. But when leading a trip as a guide the dynamic is entirely different than on a vacation with friends. Being a guide puts a lot of responsibility on you—you are the designated leader, the point-person for any mishaps that occur. Many guides are barely over 21, yet are entrusted with the health and safety of people venturing out into the backcountry—in my case, being entrusted with other people’s children. Perhaps some guides can give the air of being completely carefree, but the position actually requires constant vigilance to maintain the safety and well-being of all the participants.

Additionally, there are always the hum-drum tasks that are part of the guiding position. With so many trips coming and going, I was always in the process of unpacking the previous trip while outfitting for the next one. My guided trips were all of a similar nature, so I ended up doing lots of things over and over again: setting up tents, cooking campfire meals, doing camp dishes, loading and unloading gear, even paddling down the river could become mundane at times. Although a lot of these campcraft tasks are intrinsically enjoyable to me, doing these same tasks trip after trip for a job instead of for personal recreation turned some enjoyable tasks into a chore instead. On my own personal trips, I could do the same amount of work with hardly noticing, but when it’s part of the job description, unfortunately, it can feel more obligatory than self-initiated.

Even for as much work as a fun job like guiding can be, all the hard work seems worth it when the participants on your trip say they really enjoyed themselves. Leading trips may be your job, and you may have to go canoeing and camping on days you’re not feeling up to it. You may have even run this particular trip half a dozen times this summer already. But for the people you are leading, the days they are on a trip are something out of the ordinary. It is far different from the regular hum-drum of their daily lives. These participants come outdoors and notice the beauty of nature and appreciate the recreational activities with fresh eyes and happy expressions. It really makes my trip when I’m reminded of that.

The Mud Puddle Ecosystem

Near where I live, an outbuilding was raised this summer. Down a gravel road then along a sandy two-track, the building stands new and distinct in a recent clearing in the woods. Earlier this summer construction vehicles often came and went, their heavy treads leaving a growing impression upon the sandy-clay soil. Spring rains had raised the water table and kept the soil saturated, making the soil easily molded by the tracks of heavy machinery. Every vehicular pass widened the quaint two-track until all the median vegetation was turned under and the ruts grew deep and muddy. Spring storms sent water flowing into the new depression; it was the genesis of a mud puddle.

I had walked past this puddle frequently during the summer. Always skirting around its edge, I never wanted to risk fully submerging my feet into the murky depths. Though it could feasibly be jumped across at places, it took fifty paces to walk entirely around. Getting too close to the edge was always risky. The waterlogged soil around the perimeter was slick and muddy; one careless step would result in a drenched shoe. Regardless, the dampness of the puddle oozed up into each visitor’s footwear, whether they were careful or not. How deep the puddle was I never found out. Its opaque muddy waters kept the true depth from me. There must be a bottom somewhere, but it was never for my pair of sneakers to find out where.

With the outbuilding having been finished, the rumble of construction traffic stopped mid-summer. The giant mud puddle remained, now undisturbed by track or tire. Only footprints troubled the new body of water. The hot July sun did its best to transform the lowly puddle into a series of dusty ruts, but continual summer storms provided aquatic sustenance. The puddle’s existence continued indefinitely.

A few weeks passed since the times I walked by the fledgling puddle in early summer. I remembered the puddle’s brown murkiness and the primordial look of its oozing mud. Yet, as I meandered past once again, I was drawn in closer. A sudden burst of movement caught the corner of my eye. Curiosity overcame me. In childlike wonder I stooped down to investigate what happened. A bullfrog had jumped into the mud shallows. Disturbed by my movement, the frog sought shelter in the puddle’s depths. The bullfrog now sat still, wary of any movement, its eyes poking just above the waterline. In my brief observational absence, the lowly mud wallow had been transformed. The lifeless ooze had changed into a thriving ecosystem all its own.

I continued to stand and watch closer. The longer I squatted and the stiller I stayed, the more movement caught my eye. Fat black blobs swam lazily in the brown water. These were tadpoles, the maturing progeny of the bullfrogs. Had the current generation of frogs been born in this puddle? Perhaps, but maybe the current bullfrog residents had moved in and lain their young there, staking the first pioneering claims to the new habitat. Elsewhere, more black dots darted quickly below the surface of the water, stopping as rapidly as they had started. With two long oar-like legs attached to an elliptical body, these are insects known as backswimmers. They have likely flown in from similar habitat in a nearby swamp. Aquatic predators, the backswimmers indicate the presence of prey species in the puddle, some of which are too small to see. In this short amount of time, a food chain has been developed in the puddle.

The formerly impenetrable murkiness of the water had also begun to clear. Slowly, sediment had settled and the opaque brown became semi-translucent. The water still appeared brown from the muddy bottom, but light now penetrated deeper down. Mats of algae now lay revealed floating in the water. Intricate, delicate; curvy, lacy folds of blue-green. Still waters had allowed algae to grow. Their spores—have they come from a proximal swamp? Were they blown in from afar? Had the spores lain dormant on the dusty road, just waiting for the rains to come again? Algal life now flourished in the mud puddle, serving as the primary producer—the energetic foundation of the new ecosystem. Elsewhere, blades of grass had started poking up from the mud. Likely remnants of the former median vegetation, the rhizomes of the grass had survived dormancy under the mud, now sending new shoots skyward to catch the sun. The inundation of the puddle had slowly decreased enough that lengthy miniature islands had begun appearing in the terrain. These new spots of land remained moist, the perfect germinating spot for colonizing plants. Ruderal species—common roadside weeds—had begun to sprout up around the puddle. In time, these plants will fill in the disturbed soil; the mud being inevitably covered up in a blanket of green.

Where had the abundance of this mud puddle even come from? Until recently, this stretch of road was a dry dirt two-track. Now, this simple mud puddle, along the lonesome two-track road, had turned into a sonata of life. It had grown into an ecosystem of its own right, a microcosm of all life itself. What will happen to the inhabitants of the mud puddle at the end of the summer? Will intermittent rains continue to feed its life? Or will the hot August sun desiccate the puddle and all creatures within? Next year, after a long and cold winter, will the puddle still remain? Or is it really just ephemeral, making only a brief temporal appearance when summer rains come down heavier than usual? In ecology, the process of change is continual. Entire ecosystems may come and go based on such a small thing as a depression to collect water. What will be the fate of the mud puddle ecosystem? Only time will tell.

Letter from Camp

Dear Family and Friends,

Greetings from camp! This summer has flown by. I can’t believe I’ve been in camp for over seven weeks now. Just one more week and camp will end and I’ll be going home. I’m going to miss all the fun things there are to do at camp. I don’t want to go back to school so soon either 😦

I’ve been keeping very busy at camp this summer. There are lots of activities and things to do. So far I’ve done a lot of disc golf, mountain biking, ecology, and lifeguarding. Mountain biking is my new favorite activity. We get to ride the bikes around the trails at camp. Sometimes we even get to ride trails outside of camp. Last week I was riding and fell. I got a big bruise on my knee, but I’m okay :). I’m still really hoping to learn how to sail in the last week of camp. Sometimes after all the daily activities are finished, I like to sneak off with the other staff members and go for a paddle at night.

Camp is beautiful! The north woods in Wisconsin are so different from life back in the city! I swear it must’ve taken twenty hours to drive here on the busses. We’re in the middle of nowhere! Camp is surrounded by really tall trees and it’s right on the lake. It’s so different to be surrounded by all this nature. I can hear the birds chirping and see the fireflies at night. There’s even a family of bear that wanders through camp (plus there are rumors that squirrels live inside the roof of the lodge). The mosquitos are pretty bad. I’ve gone through lots of bug spray. The stars at night are amazing. One of the counselors got us up in the middle of the night to see the northern lights!

I’ve made lots of new friends at camp. Lots of people have been to camp before, so at first I thought I wouldn’t fit in. But pretty soon I couldn’t tell who is new and who has been here before. My cabin is pretty small. I live with two other trip staff and the tennis pro. We get along, but we don’t spend much time in our cabin. It gets really hot during the day, plus it’s pretty messy. I don’t think my cabin will ever get a cabin pride award for cleanliness.

I’ve hung out with lots of different campers this summer. It’s surprising how easy it is to make friends with people. The youngest campers like to have lots of fun. We play in the water or go down the slip-n-slide. The older kids are cool. They know a lot of stuff and are really good at sports. I wasn’t sure if they’d want to hang out, but they all say hi to me and include me in activities too.

I can’t wait to go back home and have some of your food, Mom :). The food here is awful. I’m so sick of eating tinfoil surprise. There’s a salad bar, but one of my cabinmates always hogs the salad bar pass. By the time I get to the salad bar the yogurt is always gone and there are beans dropped in the cottage cheese. We used to have dessert at lunch, but then the kitchen started giving us fruit instead. We can’t have peanuts at camp either. We have this fake ‘peanut butter’ made of sunflower seeds. It’s called Sunbutter. People say it tastes terrible, but I really really like it. I want some more when I go back home. The thing I look forward to most at mealtimes is cheering after we are done eating. My cabin doesn’t cheer the most, but when we want to we can be the loudest to pound on the tables.

Each day we wake up to the camp bell. Most of my cabin mates have to rush to breakfast.If you’re last, then you have to clean up after the meal. Sometimes I get up really early in the morning to walk around while it’s still quiet. I get to see lots of animals that way, like giant snapping turtles. After breakfast we have to clean up our cabins. Then we have two different activity periods before lunch. After lunch we have a rest period. Camp makes us write letters during rest period, or else they won’t give us our mail :(. After rest period we have two more activity periods and then an hour of organized free time before dinner. Our evening program is always different. Camp has a lot of fun games that they do every year.

I’ve gone on lots of trips this summer too. Each cabin gets to go on their own wilderness trip. The youngest campers go on the Namekagon, Saint Croix, or Flambeau rivers. My favorite trip this year was on the Brule River. That was a four day trip with really hard rapids. The last night of the trip we stayed at a creepy campsite haunted by the ghost of a baby-snatcher. I can’t wait until I can go on the Canadian in two years as a Pine Manor camper. This year I also went on two mountain biking trips and did an overnight solo trip. I was pretty scared to sleep out in the woods by myself with nothing but a tarp. But I survived and I’m really proud of myself!

Gotto go. There’s a game of North Star Ball coming up after rest period.

Miss you all. Can’t wait to see you soon 🙂

Camper Ty

A Canadian Coming of Age

“There is magic in the feel of a paddle and the movement of a canoe, a magic compounded of distance, adventure, solitude, and peace. The way of a canoe is the way of the wilderness and of a freedom almost forgotten. It is an antidote to insecurity, the open door to waterways of ages past and a way of life with profound and abiding satisfactions. When a man is part of his canoe, he is part of all that canoes have ever known”

-Sigurd F. Olson-

The Canadian. A non-specific phrase in its own right, but at North Star Camp for Boys, a phrase loaded with connotations of all caliber. At camp, talk of the Canadian points specifically to the many facets of one thing—it is the epic journey, a bildungsroman, a rite of passage unambiguously for the boys of North Star. Steeped in over 50 years of tradition, this outdoor trip to the wilderness of Ontario’s Quetico Provincial Park proves itself as an experience of a lifetime.

They have been looking up to the Canadian trip since they were first year campers—with apprehension, fear, wonder, amazement, longing. They have heard various tales and rumors about this trip from their friends, older brothers, or even their fathers who have completed the trip long before them. Successive cohorts of campers go on the trip and make their return, detailing the experience with tall tales and exaggerated truths. Each year spent at camp, the young boys see the Canadian trip getting closer and closer.

The Canadian is the culmination of North Star’s progressive outdoor tripping program. Every year at camp, the campers take a longer and more difficult outdoor trip. The youngest campers begin with an overnight canoe trip on a nearby docile river. River trips then become progressively longer and more technical as the campers mature developmentally. The year before their Canadian, campers trade in their canoes for packs and go on a hiking trip the length of five days and four nights. The following year, the Canadian trip more than doubles the amount of nights spent in the wilderness. Such an extensive experience is the Canadian that of an entire summer spent at camp, activities directly and indirectly related to the trip take up a quarter of the summer.

The mere thought of spending that much time out in the Quetico Wilderness proves intimidating to some of the boys. The mental and physical endurance required to complete the trip is much higher than any trip these boys have yet completed. Some doubt their abilities to complete the trip. Still, generation after generation of North Star campers handily complete the journey. It is a coming of age for all who undertake it. Though they are becoming young men, they are still a group of children; at only 14 or 15 year old, this is their last summer at camp as campers. The Canadian is the final transformational process in which these boys become men; a more tactile transformation than the symbolic coming of age of their Bar Mitzvahs only a couple years earlier. The transformation of the boys on the Canadian is one that they’ve earned through their hard work and endurance on the journey.

The Canadian, in a way, is a process of giving tangible hardship and practical challenge to a group of campers who face reduced adversity in their normal lives. Most campers attending North Star live in wealthy suburbs and come from privileged families who can afford to send their children to such a camp. North Star itself is not an outdoor camp either—it is a traditional residential summer camp with a tripping program only as one small component. Although every cabin group goes on an outdoor trip each summer, most campers do not come for the trips themselves. Though some boys love the trips, others can’t wait for them to be over.

The Canadian, though always shrouded in mystique, was never anything more than the campers could handle. In fact, the challenge of Canada was substantially less than what it’s made to be. The gestalt of the journey may seem intimidating beforehand, but in reality the pilgrimage consists of nothing more than small obstacles to be overcome in the here and now. Looking back, the group of campers who I led should be proud of what they accomplished. Over the course of 9 days of wilderness travel, my camper group canoed over 105 miles and portaged the entire outfit over 7 miles in 22 separate portages. We faced variable weather, changing from intensely sunny and hot, to shivering cold and wet. Thunderstorms had us seeking emergency shelter off the lakes multiple times, and after storms on the second night soaked most of our gear, everything stayed damp with periodic rain and storms the remainder of the trip. We found strong headwinds could delay forward progress despite everyone’s strongest paddling, or a long muddy portage could take over three hours to complete and leave us pitching camp after 9 at night. Some nights dinner was freeze-dried lasagna unintentionally prepared as a soup, or our rations were reduced because of mice foraging in the food packs. My group even experienced an emergency seaplane evacuation of one of the campers on the second day.

The boys on my trip were thrown a lot of adversity, but the way they handled it was most indicative of their maturity. Though there was much to grumble about, there was little complaining out of sheer desire to complain. The tasks that needed doing were done, eventually with less prodding from me as the guide. Most importantly, a general good attitude was maintained throughout the duration of the trip. My camper group proved to me what maturing men they could be, and what they could handle in the circumstances. As well, the camper who was seaplane evacuated returned later to the group and finished the trip strong.

As an outsider to North Star’s 72 summers of tradition, I had to quickly learn the sheer importance of a trip like the Canadian. At pre-camp training, many of this year’s Counselors-in-Training (who were campers last year) said that their most proud accomplishment was completing the Canadian. At a Friday night ceremony with the entire camp staff later, when everyone was called to share a sentimental object, many more camper veterans brought objects associated with their Canadian journey. Even the camp’s program director, a North Star veteran of 30+ years, brought the souvenir of his first Canadian—a Loony Dollar—that he has kept tucked in his wallet since his first Canadian experience in the early 90’s. As a newcomer to North Star and as a first-year trip leader, I was honored to have the pleasure of being a guide for such a pivotal trip. As a guide, mine would be the responsibility of leading these boys safely through the wilderness and ensuring that they get the most out of their Canadian experience.

As much as the Canadian is a coming of age for the campers, the trip was a coming of age of my own. This Canadian trip was my induction into outdoor guiding, the first trip I ever led as a professional guide. Every trip experience before had been recreational and informal, either taken by myself or with my friends. For the first time, I was the officially responsible party for the safety and well-being of 12 children and two young adult counselors. I was tasked with making the trip a success and making sure the campers got the most out of their experience. Overall, my trip was an unqualified success. I surprised myself at how I could lead others in the wilderness just as much as the campers surprised themselves by completing their Canadian.