Category Archives: Reflection

Confessions of a Trip Leader

The crew of the first trip I ever guided–a nine-day trip to Ontario’s Quetico wilderness

Getting paid to do what you love for a profession—an idea very appealing to a young, idealistic adventurer. We all have to work to earn a living anyway; might as well find a way to get paid for our passions. For myself, I really enjoy spending time in the outdoors, visiting wild places and traveling in the backcountry. Even if I held a conventional job I’d be doing these activities in my own free time. So, with an ample demand for outdoor guides in the recreation industry, why not become a guide and get paid to do my favorite pastime? Plus I’ve always enjoyed outdoor trips more when I’m with people to share it. Thus working as an outdoor guide seemed like an ideal position for me: I’d not only get to take people to spectacular places in the outdoors, I’d earn a livelihood from it as well.

I had entertained the fantasy of being an outdoor guide for a long time coming, basically ever since I went on my first guided trips and learned that guiding can be a profession. The outdoor guides leading me had always seemed to carry a certain aura to them: super-engaging, energetic, and adventurous. They got to spend so much of their time going out on trips or hanging out and goofing off at the outfitters. I perceived them as experienced gurus capable of surviving outdoors under any situation. They also seemed timeless—living eternally in the carefree moment of the trip and not caring about what happened before or what would come after a trip. Most important of all, they all seemed to be having fun no matter what. This was my preconceived notion of who outdoor guides were.

Now I’ve completed my first experience on the other side. Technically I have been a professional guide, since I received compensation for my guiding services. Yet it still feels really out of place and especially undeserved to consider myself a professional. I still feel like such an amateur, and so many of the skills required for the job I’m still developing. But as I’ve seen from employment, aside from the rudimentary outdoor skills needed to run a trip, a guide doesn’t need to be a technical gearhead at all. In my case at North Star Camp, I wasn’t hired for my technical skills—I was hired for my judgement and ability to relate to children. My guiding job was a whole lot more social than I expected; and perceptive social skills more so than advanced technical skills really make each outdoor trip memorable.

North Star Camp took the kind of people they wanted to hire and made guides out of them. Most trip leaders at North Star, like me, had very little canoeing experience prior to the summer; some had never even canoed before. But we all learned quickly. So many of the requisite technical skills of guiding can be trained in a short period of time. In my case, this included basic wilderness medical safety gained in an eight-day Wilderness First Responder Course followed by an intensive two week trip leader training conducted by North Star. All the trip leaders at North Star Camp this summer were first-time guides; our training consisted of an abundance of practical practice as we essentially scouted all of the trips we would be taking the campers out on. By the time the first campers had arrived for the summer, I had undergone nearly a month of training. By then I was more than ready to start guiding people. Adding campers to each trip just seemed like the next logical step—not much of a stretch at all.

However quickly technical outdoor skills can be taught, the parts of guiding that are most difficult to train are the interpersonal skills and social perceptiveness needed to effectively lead a group through the wilderness. The social aspect of the job can be touched upon during training, but so much of it is developing your own guiding personality from experiences gained on the job. Being an outdoor guide is quite like a big game of improv, a constant flux of evaluating the conditions and then adjusting plans based on a reading of group dynamics. Should we break for lunch here or there, now or later? Should we get to camp early or sleep in late? Does the group want free time or more structured activities? Aside from the generalized structure of a trip which details major trip checkpoints, a lot of events on the trip are still unknown even to the guide. Most of the time we’re just one step ahead of the group with our decisions, but we pretend we had an exact plan in mind the entire time. So much of guiding is just acting the part, looking confident and making decisions on the fly. Constantly we keep weighing multiple scenarios in our heads, evaluating which ones would benefit the group the most based on continually changing circumstances. Although before each trip goes out there is a lot of prep work in order to be adequately prepared, once you’re out in the field there’s a limited amount of control over the circumstances—everything else is just improvisation and making do with the conditions.

So much of being a guide is acting the part

Being an outdoor guide may have been the most fun job I’ve ever taken, but still it’s a job. Getting paid to take vacation after vacation is not the right idea for it. Sure, I’d be inclined to take personal outings to the places I led trips this summer. But when leading a trip as a guide the dynamic is entirely different than on a vacation with friends. Being a guide puts a lot of responsibility on you—you are the designated leader, the point-person for any mishaps that occur. Many guides are barely over 21, yet are entrusted with the health and safety of people venturing out into the backcountry—in my case, being entrusted with other people’s children. Perhaps some guides can give the air of being completely carefree, but the position actually requires constant vigilance to maintain the safety and well-being of all the participants.

Additionally, there are always the hum-drum tasks that are part of the guiding position. With so many trips coming and going, I was always in the process of unpacking the previous trip while outfitting for the next one. My guided trips were all of a similar nature, so I ended up doing lots of things over and over again: setting up tents, cooking campfire meals, doing camp dishes, loading and unloading gear, even paddling down the river could become mundane at times. Although a lot of these campcraft tasks are intrinsically enjoyable to me, doing these same tasks trip after trip for a job instead of for personal recreation turned some enjoyable tasks into a chore instead. On my own personal trips, I could do the same amount of work with hardly noticing, but when it’s part of the job description, unfortunately, it can feel more obligatory than self-initiated.

Even for as much work as a fun job like guiding can be, all the hard work seems worth it when the participants on your trip say they really enjoyed themselves. Leading trips may be your job, and you may have to go canoeing and camping on days you’re not feeling up to it. You may have even run this particular trip half a dozen times this summer already. But for the people you are leading, the days they are on a trip are something out of the ordinary. It is far different from the regular hum-drum of their daily lives. These participants come outdoors and notice the beauty of nature and appreciate the recreational activities with fresh eyes and happy expressions. It really makes my trip when I’m reminded of that.

Go Find Yourself

My travels in Australia could have been cast as the prototypical coming-of-age journey: a young man goes to a far off land alone to find himself.

But I didn’t go to Australia to find myself. I knew too much of myself already. Instead, venturing to Australia was more an exercise in trying to lose myself—to get out of the person who I knew too well and to try a different lifestyle for a change. Australia would be a place I could be free to experiment with identity.

Young people finding their identity is perhaps the defining mark in the transition from childhood to adulthood. As developmental psychologist Erik Erikson would describe it, the primary existential question of emerging adulthood (Stage 5) is that of Identity versus Role Confusion. Classically portrayed as the angsty teenagers’ struggle for self, this stage of psychosocial development often lasts into young adulthood, ending when the individuals’ personal identity becomes fairly consistent for the remainder of life. Though the age individuals go through this stage varies, the greater struggles of Erikson’s Stage 5 will typically be resolved around my age, sometime in the 20’s.

Thus, going to Australia didn’t necessary teach me who I was; more so it reaffirmed who I was already. As a result, I had inherently less identity formation to undergo, and was faced instead with a related identity struggle—figuring out how to live the rest of my life with this person I’ve grown to be.

In my challenges with my identity, there are things I know about myself that I struggle with accepting. There are some things I wish I could be just a little bit different—I’m terribly shy and introverted; spontaneity is quite a ways out of my comfort zone; I tend to take everyday matters way too seriously, etc. The list could go on about things I believe society expects me to be, but that I feel I just don’t measure up to.

Travelling to Australia, I held the assumption that going to an exotic country where no one had any pre-conceived notions about me would allow me to branch out and escape the confines of my identity—in particular my temperament and personality. For once I just wanted to let loose, be spontaneous, hang out, party, and disregard the consequences. I also thought I’d play with some career roles by trying out jobs I’d likely never do in the States—fast food drone, a sociable waiter, the hospitality industry. I’d also grow out my hair one more time before I had to permanently adopt a well-groomed hairstyle for the remainder of my professional life.

Alas, I didn’t find myself becoming the wild, long-haired, care-free holiday-maker I had envisioned before my trip. Instead, my standard temperament took the reins. In Australia I struggled to be outgoing and to meet new people; I rarely was spontaneous and light-hearted enough to party in spite of the consequences; I never found a job in the service industry; and I never grew my hair out before getting fed up with its wild antics.

In the end, I found that I just couldn’t lose myself in Australia, though I put in a genuine effort to try out different roles for a change. Instead, my reliable temperament shone through even in my new surroundings. Like Socrates’ famous mandate I just couldn’t help but to “know thyself” even Down Under.

Moving forward, my challenge is to accept myself for who I know I am instead of thinking that a different persona is more desirable or acceptable. How can I make the best use of the character I’ve developed? What role do I fit into in adult life? Instead of seeing them as weaknesses, how can some things about me that I’m uneasy about be used as assets?

Going to Australia may have been the final throes of my greater struggles in Erikson’s stage 5. Sensing that I was nearing a very stable sense of self, I felt the necessity to try on different roles while I still had the freedom to experiment. For the most part, though, my personal character has cemented, deepened in part by the challenges I presented myself in Australia. Some conflicts of Stage 5 still remain, namely those of finding a career path and determining my role in the adult world. But on the whole, the person who I am today is the person I have found and have chosen for myself. For all its strengths and seeming inadequacies, I’m happy for that person.

Ghosts of Port Arthur

Recently I took a journey to see the ruins of Australia’s most renowned convict site, the penal camp at Port Arthur, Tasmania. Looming sandstone ruins lie sullenly at the site; their walls remain silent yet beckon the visitor to come closer. Port Arthur is rumoured to be decidedly haunted. On a gloomy day, one can nearly hear whispers from the horrors of convict transportation. Upon reforms of the penal system, transportation of British convicts to Van Diemen’s Land (modern Tasmaina) ceased in 1853, and Port Arthur finally closed as a penal site in 1877. Soon after its closure, Port Arthur became a tourist attraction for those curious to learn about the depravities of humanity that occurred there.

The ruins of Port Arthur, Tasmania

The oldest buildings at the Port Arthur site date from the mid-1800’s. Today these old sandstone edifices stand as hollow shells after bushfires gutted the buildings post-abandonment. However, one modern building on site also stands as a hollow shell—a memorial to another dark time in the Australian nation’s past. This building is the Broad Arrow Café, the site of Australia’s worst mass shooting in national history. On April 28, 1996, a lone gunman walked into the café and opened fire, initially killing 20 victims in a shooting spree that would go on to take the lives of 35 and injure dozens more.

The Broad Arrow Café.

I was alive when the Port Arthur massacre took place. I was five years old at the time, older than the youngest victim, but too young to understand even if I had known what had happened. In no way do I have personal connections to the Port Arthur site—yet I still felt drawn to the memorial as a sacred pilgrimage. As an American, I am a citizen of a country that knows gun violence too intimately. I can’t help but feel sympathy for those whose lives are devastated from senseless violence. Akin to a stranger mournfully walking through an unfamiliar cemetery, I felt the need to pay my respect to those who had died in the Port Arthur tragedy and, symbolically, to others in similar incidents around the world.

Only a few weeks into my travels in Australia, America once again faced the consequences of another mass shooting. December 2, 2015, San Bernardino, California. The news broke from the TV in the hostel I was staying in. Though I don’t even watch television, I couldn’t pull myself away. Before San Bernardino, I had always stayed informed on the all-too-many mass shootings in America. But this time I was watching from abroad. I had become a distant observer behind a glass panel. Witnessing the events from abroad, I couldn’t help the overflowing sadness of lament for my country, a land that allows such tragedies to happen continually. I felt angry at the ineffectiveness of any sort of reform that would unite my country to curb the violence. That morning I shed a tear of sorrow for my country.

I visited the Broad Arrow Café at Port Arthur thinking that I’d learn a lesson on how one nation responded in a unifying manner to prevent future tragedies from happening. But gun control lessons weren’t the point of the memorial. The empty shell of the café is rather a somber place to mourn for those 35 taken. It’s a touchstone for reflection.

In matters of gun violence, the difference between Australia and America is that one country was united enough by tragedy to act. In the wake of the 1996 massacre, strict, nationwide gun control laws were passed—semi-automatic assault weapons were banned, a nation-wide gun registry was implemented, and gun buy-backs were held. Australia soon developed one of the most regulated gun markets in the world. As a result of the reforms, gun violence in Australia plummeted drastically. A telling sign of the effectiveness of one country’s reaction is that no mass-shootings on the scale of the Port Arthur Massacre has occurred in Australia since.

Places like Port Arthur stand as a sentinel to the past. We remember and sojourn to these places because we can learn from the mistakes of days gone by. The convict transportation system at Port Arthur shattered lives with its cruel ad unjust punishment, just like a mass shooting at the site shattered lives 20 years ago. I want to believe we can learn from the mistakes of our past and forge a better future. I want to believe we can unite and act before more tragedies occur.

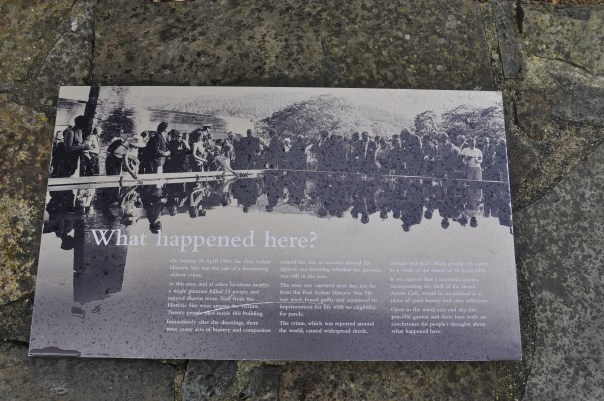

Memorial Plaque at the Broad Arrow Café.

Transcript reads:

What happened here?

On Sunday 28 April 1996, the Port Arthur Historic Site was the site of a devastating violent crime.

In this area, and at other locations nearby, a single gunman killed 35 people and injured dozens more. Staff from the Historic Site were among the victims. Twenty people died inside this building.

Immediately after the shootings, there were many acts of bravery and compassion around the site, as rescuers tended the injured, not knowing whether the gunman was still in the area.

The man was captured next day, not far from the Port Arthur Historic Site. He was tried, found guilty and sentenced for life with no eligibility for parole.

The crime, which was reported around the world, caused widespread shock, outrage and grief. Many people still suffer as a result of the events of 28 April 1996.

It was agreed that a memorial garden, incorporating the shell of the Broad Arrow Café, would be established as a place of quiet beauty and calm reflection.

Open to the wind, rain and sky, this peaceful garden and these bare walls are touchstones for people’s thoughts about what happened here.

Home is Where the…(wherever)

The skyline of Hobart, Tasmania nestled between the sea and mountains

space

“This is the most beautiful place on earth. There are many such places. Every man, every woman, carries in heart and mind the image of the ideal place, known or unknown, actual or visionary. There’s no limit to the human capacity for the homing sentiment.”

-Edward Abbey, Desert Solitaire

space

One challenge for my time in Australia was to come up with a definition of what home means to me. The origin of this question goes further back, though, stemming from several protracted conversations with friends on the topics of home and place. As part of a generation coming of age in an increasingly globalized society, the question of home is no longer as limited as it used to be. Instead, rapid global travel and communication technology allow for a more mobile and connected society. Our options of where to live, work, and play quite literally span the globe. Yet, the idea of discerning one’s home in the vast world still constitutes a fundamental part of our identity.

As for myself, I feel like home could be anywhere. That’s to say that home isn’t necessarily a physical location in particular, but an idealized interaction with a location in general. Though I have travelled through admittedly very little of the world and have not experienced substantially different cultures, I can see a trend in my interaction to new places. Foreign locations become less foreign with familiarity. Given enough time, I feel that eventually I could make a home on any corner of the planet and be content with that location. This is not a judgement of place, but a judgement of my interaction with places. Home, then, is a process. It’s the homing sentiment.

Fundamentally, to me the question of home comes down to the concept of rootedness. How rooted do I feel to a certain place? My answer to that question is that I’m yearning to be rooted to any place at all. I struggle greatly through my travels with feelings of transiency and impermanence—essentially a new kind of homelessness. I yearn to be connected to a place at a more than superficial level, and any place could ultimately fill that desire. This is why, among other things, when I’m travelling I feel the need to stop at interpretive signs detailing local history—about the actions of city residents long dead or buildings long ago razed even though it may have little personal meaning to me at the moment. Doing such is just one small tangible way of discovering more about a place that leads me to a feeling of connection—that I belong more to a place now that I know more about it.

Given enough time, my habits of interaction with unfamiliar places should lead to a greater sense of home within each place I stop. Along with my habit of learning local history, I also tend to eschew corporate retailers in order to patronize businesses I could find nowhere else, take ambling walks along city streets to understand geographical differentiations within the city, and take note if I see local faces more than once. In short, in each new place I try to understand the local identity. I try to live like a local. This, fundamentally, is the reason why I feel like I could find sentiments of home in any geographical location.

However, though I feel like any geographical location could ultimately become a satisfactory home, some places I visit certainly seem more likely candidates. As someone who studies the natural environment and geography, the landscape—physical and cultural—plays an elevated role in the homefulness of a place. In my Australian travels, some places lend themselves more readily to sentiments of home; towns like Orange, Tumut, or Hobart sparked a sense of rootedness in me quickly. Other places, such as Maroochydore, felt reprehensible at first but inevitably grew on me endearingly. If nothing else, my period of meandering travel in Australia has helped me refine the qualities of a place that most readily resemble a home for me.

In a globalized society, the whole of the earth could theoretically be my home. Such possibilities create a world of geography to navigate in finding one’s place. For me, home is still an ongoing conversation, and I still have a lot of geography left to navigate.

***

‘I cannot honestly say that I liked Canberra very much; it was to me a place of exile; but I soon began to realize that the decision had been taken, that Canberra was and would continue to be the capital of the nation, and that it was therefore imperative to make it a worthy capital; something that the Australian people would come to admire and respect; something that would be a focal point for national pride and sentiment. Once I had converted myself to this faith, I became an apostle.’

-Former Prime Minister of Australia, Robert Menzies, reflecting on his changing attitudes towards Australia’s national capital Canberra.

A Working Request

Sometimes searching for employment feels like being lost in a maze

Dear Future Employer,

I know my time of long-term future employment is still a ways off, but I’ve been thinking a lot about occupations lately. That’s probably no surprise, seeing how in Australia I’m always on the lookout for the next job. And, even when I have found a job here, they’ve lasted only a few weeks—so it shouldn’t be a surprise that I’m constantly on the job search. After all, I do need some means of paying my living expenses and saving up for future travel.

Future Employer, I look forward to the day when we can form a mutually beneficial team, where you benefit from my skills and I benefit from the position. I’m growing tired of the unceasing job search in Australia, and I hope our future relationship will last a bit longer than a few weeks. How much longer our working relationship should last, I can’t say at this point—it could be months or it could be years. It just depends on how well we get along. But, my Future Employer, when I do return to the States and start working for you, here’s a few things I want you to know.

Future Employer, please know that I do not work for economic reasons alone. Though western society may be set up in a way that I need money to support myself, please note that a high income is not my employment objective. If you are offering a position that is not something I want to do, there is no way you could pay me enough to do it for long. I’d rather do something I love as my occupation, even if that means living at just a little lower economic status.

Also, Future Employer, when you do finally employ me you will find that I throw my all into my work. Some might say I’m a bit of a workaholic, though that’s not quite the way to describe it. Rather, my daily occupation forms a huge part of my identity; it was when I was a student and has been in all the various jobs I’ve worked. I find that it’s difficult to separate who I am from the work that I do. Thus, long-term employment is not a decision I take lightly—my future profession must be a reflection of the beliefs and values that I hold dear. So, Future Employer, I’m not just looking for a job. I’m looking for a calling. I’m seeking to use my occupation as a means to make a real difference in the world. In the words of my Alma mater, I’m in search of my vocation—the place where my deep passion meets the world’s needs.

So, my Future Employer, I’ve come up with a list of ‘Working Demands’. If you can’t meet these demands, I’m afraid I won’t be happy working for you:

- Allow me to take pride in the work I do for the sake of the job. Nothing in a job cuts me down more than being explicitly told to cut corners or to do shoddy work for the sake of earning a dollar.

- Respect my time, efforts, and contributions. I am not your commodity used to earn you a profit. I am a human worthy of dignity and respect.

- Treat my employment as an investment, not a liability. As my employer, be my coach to improve my performance, not my overlord to punish me for mistakes.

- Promote a good cultural environment among the workforce, such that we are not just co-workers but members of a team working towards a vision. As a bonus, I wouldn’t mind getting to know my co-workers well enough personally to even spend time outside the workplace with them recreationally.

- Let me try out my own ideas to promote innovation, and give me the flexibility to try and fail sometimes, because making mistakes is all part of the learning process.

- Allow me time to work on my individual ideas, but also have me work in a mutual and collaborative team environment.

- Keep me mentally stimulated. Provide tasks that keep me learning and growing.

- Provide me with a variety of tasks in the workplace, so daily assignments are invigorating instead of monotonous and dull.

- Give me flexibility. The strict pattern of 9 to 5, Monday to Friday, and wearing business casual has never really appealed to me.

Someday we will find each other, Future Employer. If you offer to meet my working demands, you will find me a strong and passionate worker.

Yours Truly,

Tyler M. Bleeker

Moving On…

Sunset over the Sunshine Coast city of Mooloolaba

Tonight I sit reflectively on the spit as the sun sets, watching the distant foreshore of the Sunshine Coast as darkness falls and the city lights come on. Tonight is my last night here. Tomorrow I will move on.

Lychee harvest ended today. We had a celebration cookout under the veranda with all the workers, celebrating the achievements our labour accomplished. Afterwards we began our goodbyes to the crew we have known for a few short but intense weeks. “See you around,” say some as they leave the farm. “See you in Stanthorpe,” or “See you Tumbarumba” say others, gaily announcing their next planned destination, as if we expected to run into one another again. Joining the trend, I dismissed myself to the crew with “catch you in Batlow!”

But as I watch the sun set over the hinterland mountains, I contemplate why it is that I am moving on already. I didn’t even plan to be out here tonight—I had planned to stay inland to prepare for my upcoming departure. But something innate drove me to the coast. I just had to be here for one last night.

I have only been on the Sunshine Coast for a mere 31 days—longer than a visitor, but far short of being a local. I’ve just begun to know this strip of coastline and the lifestyle it affords. For a while, this place was my home. Why, I wonder sometimes, must I constantly be moving on right when I begin to know a place?

Australia, of course, is a different situation for me. Here I have no opportunity for permanency. I am no more than a long-term visitor, with a definite end-date for my time. My transiency is based out of the necessity of economics, continually chasing employment to support my holiday further. With immediate job opportunities on the Sunshine Coast having dried up, the promise of bountiful harvest labour now beckons me elsewhere. And too, I’ve created a busy itinerary for myself to see as much of Australia as I can—the breadth of my travels could not be reached if I do not continually move on. My own disinclination to linger beyond planned has left me a drifting traveller.

But I look onwards as the gleaming lights come on the high-rises above the beaches of Mooloolaba and Maroochydore. I wonder if I’d have the courage to deny my pre-conceived itinerary and continue to stay somewhere—merely because I enjoy the place. Would I brave enough to stop my relentless pursuit of places unknown (and potentially better) because here I have found something I’ve enjoyed?

I come from the generation sometimes characterized as ‘The Young and the Restless’. We move around easily from place to place, seeking localities suitable to our young, sociable lifestyles. No place is stayed at for too long if there is something better to be found. Myself, I always seem to be moving on from the places I have known out of a vital curiosity—an instinct—that there is something new, different, better out there to find. I feel convinced that if I stay too long in one place, I might not discover something else that fits me better. But I question my own logic. I’m too afraid to lose the illusory opportunity of something more promising that lies just beyond the world of the familiar.

I am one of a generation of cropped roots. Transiency describes my lifestyle, but I wonder why I always must be moving on.

In a Land without Thanksgiving

Today, as many Americans gather with family and friends around a dinner table to partake in the traditional late November Thanksgiving feast, I find myself in a country that does not celebrate a similar national holiday. From its North American origins, the idea of an official Thanksgiving holiday never spread to mainland Australia. Yet, even though I miss the traditions of the holiday as I stay in a land that doesn’t celebrate Thanksgiving, I still find myself having a lot to be thankful for:

- Support from Family and Friends. I am grateful for the encouragement to travel that I have received—and continue to receive—from those at home. But I also realize that there are people out there who are lonely this holiday season or who don’t receive support from others. May we reach out to those who are alone.

- The Ability to Travel Freely. I am thankful for the ability to freely and easily travel internationally without fear of danger, and I’m also thankful that people from other nations are able to travel so as to create cultural interchange and understanding among different nationalities. But I realize that there are people in the world who can’t freely travel from or within their own country, or refugees who are forced to travel from their homes, or people whose safety in daily life remains uncertain. May we create a global society that encourages travel and cultural exchange, embraces refugees, condemns violence and hatred, and is understanding of other cultures.

- The Financial Security to Delay Employment. I am thankful that I was able to have employment throughout the duration of my education, allowing me to save money and create the financial security that allows me to delay future employment and travel instead of working. But I realize that many people today remain financially insecure, cannot find a job, or cannot afford the luxury to not work. May we create a civic society where any worker can get paid a fair living wage, social welfare looks after those who are disadvantaged, and the youngest generation is not burdened by educational debt.

With today’s traditions of thanks and gratitude, take a moment to reflect on the things in your life that you’re thankful for. Also consider how we might craft a society where more people will have more to be thankful for in the Thanksgivings to come.

Pick a Direction and Go with It

So what exactly led me to venture on my own to Australia? The answer isn’t quite so simple, and there’s more than just Australia that prompted the decision. Let me explain…

Ever since we are young, we are told we can be anything we want to. As young children we were asked by earnest adults to imagine what we wanted to be when we grew up. Going through high school, we took career exploration tests and were told to explore any career we could see ourselves doing. In college, we got our free range of majors, being able to even create our own major if that’s what suited us. From early on, those of us lucky enough to come from supportive backgrounds have received nothing but encouragement telling us we are able to do whatever we want to in life.

Then comes graduation. Then comes the quote/unquote “real world” where we are faced with a completely different prospect than what we’ve experienced before. Out of school and applying for a job, we may find that our chosen major is not a good fit for an employer, or that our experiences do not fit the required skills for a desired position. We may begin to experience regrets or remorse about the school or the field of study we chose after four years of scholarship; our interests—indeed ourselves—may have changed dramatically in the course of our education. Faced with uncertain prospects about the future, we may start to wonder if the decisions we made to get us to this point were the right choices to make. A little bit older and more educated now, we look with hindsight to see how our past choices have put a limit on our current prospects.

This situation prompts the genesis of the quarter-life crisis. For us who were told all along we could be anything in life we wanted, we are now finding that belief quite doesn’t hold true. Past decisions, as well-meaning as they may have been, have now limited what we can do in the future. Although we are still young and have many opportunities to change our direction, we find that such a move would require either un-doing or overlooking so much that we’ve already worked so hard to accomplish. At this juncture of our lives, we wonder if we’ve made the right choices up until now. To me, it’s this sudden realization that the world is no longer as open as we once believed that is the defining mark of the quarter-life crisis.

Maybe the quarter-life crisis is new or unique to the Millennial Generation. Maybe it just feels more pronounced now that the world is literally at our fingertips. Opportunities of what can be done tend to increase generation after generation, now seeming to reach a fever pitch in today’s society. Our culture has been breed to ‘have it all’. But having it all—having all options on the table—presents a dilemma. With so many options to choose from, our minds are unable to weigh all the pros and cons of a decision. We become intellectually burdened with the stress of not knowing which choice is the optimum one. And for some of us, the stress of not knowing which of the available options to choose can be paralyzing. This inability to make a decision in the face of limitless options is known as choice angst. Partly through graduate school and weighing my own next steps, I came upon this podcast produced by Radiolab that described the phenomenon of choice angst, https://www.wnyc.org/widgets/ondemand_player/radiolab/#file=%2Faudio%2Fxspf%2F91641%2F. I self-diagnosed myself almost immediately.

You see, as we get older, we have to make decisions in order to move on in life. And those big decisions that we have to make continually feel like they have more and more weight. Because for every decision you make—what job do I want, where do I want to live, who do I want to marry—you realize that you are closing doors on myriads of other possibilities. And those possibilities you decline could be equally as tantalizing as the ones you decide to pursue.

Thus, when I was in the course of deciding what to do after my masters program, I thought of the many different options available to me based on my particular situation. To aid in my decision, I penciled out a list of eight different directions I might go with my life. I knew that more likely than not, I’ll never get to explore all those directions that I imagined. A single lifetime is just not long enough for that. So eventually I just had to pick and direction and go with it. In the end, fruit-picking in Australia was the direction that prevailed above the others. This wasn’t necessarily because I was more interested in fruit-picking than other things, or that I felt spending time in a foreign country would benefit me more than other experiences. Rather, Australia came down to a gut decision. It really just was what needed to be done at the time.

There was no way I could have weighed out the pros and cons of every option I imagined for myself. So instead I picked a direction. And I’m going with it. Some doors may have closed because of this, but other doors will open. There’s just no seeing exactly where all this will lead.

In All Directions

I’m a millennial, one of the generation of young people entering the realm of formal adulthood. Now in my mid-20’s, I find myself in a quarter life crisis. Having followed a common pathway in American life so far, I went to college and obtained not only a bachelor’s degree, but a master’s degree to boot. A world of uncertain opportunity lies ahead on the economic playing field, but the route and where to navigate next seems to be less and less clear.

I can picture myself as in this scene from the movie Fight Club:

“I’m a 30-year old boy” (actually I’m only 25), but the sentiment’s the same. I feel in between the world of free-spirited youthfulness and serious adulthood. With one foot in both domains, I learn how to make a life for myself as an independent adult, yet remain wary of falling into the rigidity of the conventional pattern just because I don’t know what else to do. “What now?” is the question I’m at, and “Get a job,” is an answer, but what that answer looks like is yet to be figured out. Never settling for the response of “I dunno,” I go about seeking after my passions in life so much more than getting a job for the sake of having a job.

The name I chose for my blog stems from an off-handed comment my parents made regarding my post-graduation future. As I was entering my final semester of graduate school, I was weighing many possible options of what I would like to do next: fruit picking in Australia, tending a lighthouse in Wisconsin, learning organic agriculture, and joining the Peace Corps being among the many possibilities I was considering. However, nowhere on that list could be found ‘get a conventional job and climb the career ladder’. Perhaps in a fit of exasperation, my parents said that I had no direction in life. But I knew it wasn’t true. Instead, I knew I was exploring In All Directions. This life is a gift and every crevice should be explored and experienced to the fullest, in whichever direction that may be.

And thus this blog was born as an experiment in itself to complement my first direction in exploration—a working holiday in Australia. As I write future posts, these will be musings from a millennial mind. This is not meant necessarily just for millennials, but for anyone with a desire to seek, explore, and learn about the world around them. Though the theme of this blog may be one of exploration of a different country, it’s just as much an exploration of self. It’s my personal experiment with understanding myself and my place in this world, but it’s also a journey to be shared with others. And thus, this blog seeks to be an online contemplation of whatever topics may be pertinent, informative, or thought-provoking.