Category Archives: Travel

The Graduate

About this time last year I graduated from the University of Idaho with a masters degree. Being mentally and emotionally drained from formal study, I was ready to leave the cloistered realm of academia and explore the greater world on my own terms. So excited was I to get a jump start on my informal education that I left exam week early and skipped my commencement ceremony in favor of a kayak trip on the Columbia River.

Now that it’s graduation season again, perhaps I should be granted another diploma. Conceivably it could be from the University of Wanderlust. It wasn’t an accredited university. It had no designated faculty, and there were no required courses or class assignments. Tuition was also pretty inexpensive (although room and board could be costly at times). Although there were tests along the way, the entire grading system was based on pass/fail.

Yes, now that I’ve officially ended my coursework of travels, I’d say it’s like I’m a freshly-minted grad once again. My degree from the University of Wanderlust ended up being a year-long program (or else I guess I just graduated early), and I was happy to build my own curriculum too. First I spent a semester in the American West, road-tripping on a survey course of National Parks and cultural highlights. Then, I spent my second semester in Australia, taking classes in fruit-picking and van culture. From this I’ve earned a diploma full of different life experiences at an expedited rate.

And what’s more, my diploma from the University of Wanderlust focused on personal change as much as it did about learning factual knowledge. Though I enjoyed learning a great deal about many of the spectacular places in the United States as well as learning about the way of life in a foreign land, what I had set out to gain through my latest degree was deeper—a more thorough understanding of my own personal growth and moral development. My masters degree at the University of Idaho, though it challenged my intellect, lacked much of the personal growth I yearn for in education. What I needed to compensate for this lack was a challenge to develop my character and to gain a different perspective on the world.

Unlike a typical college education, though, my self-designed degree focused more on the realm of the practical rather than the theoretical. Throughout my travels, challenges were applied and consequences were real. Every event was viewed with the mindset of an opportunity to learn. Daily life became my homework assignments and the people I met along the way were became my professors.

As a recent grad of the University of Wanderlust, I feel fresh and ready to pursue a career path. Admittedly, I still do feel a little bit of the aimlessness and uncertainty of recent grad Benjamin Braddock from Mike Nichols’s film The Graduate. But on the whole, my diploma of travel in the real world has provided the necessary transition from the culture of the academic world to the culture of the working world.

Many of my lessons learned from the University of Wanderlust still need formalizing into words. But how does one succinctly sum up a year of travels? Fortunately for me (or maybe not!) I never assigned myself a term paper.

Leaving (Many) Stones Unturned

This is my first blog post back in the United States. Yes, that means my Australian adventure has ended. What I initially intended to be a year or more of work and holiday in Australia concluded after spending a comparatively short 187 days in the country.

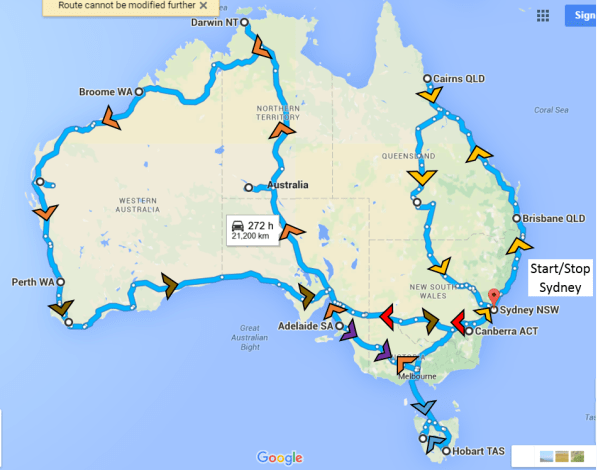

In an earlier blog post, I summarized an outline of the itinerary I had conceived for Australia. It was an ambitious plan for sure—my goal was to drive around the whole country and experience all the best that Australia had to offer. Seeing how this trip would be my only working holiday visa in Australia (and in all probability my only visit Down Under), I wanted to make the most of it. With the naïve idea that I’d be able to see everything worth seeing in Australia, I calculated a very thorough travel schedule so that I wouldn’t have to bother coming back to the country. After all, it was a long 15 hour flight from Los Angeles to Sydney just to get to Australia. Below is a map of what I originally envisioned for my year+ Down Under:

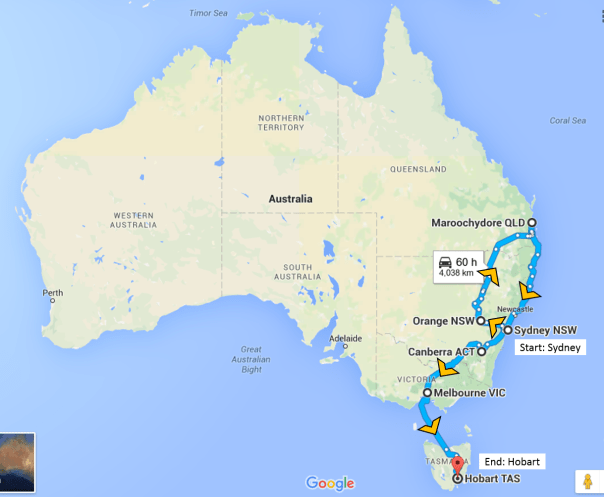

Needless to say, things didn’t work out very much as planned. Good, equitable work was difficult to find; shady fruit picking contractors swindled me out of a good chunk of my meager earnings; and my campervan experienced breakdown after breakdown. The accumulation of adverse experiences in Australia eventually led me to abandon the working holiday dream altogether. Though fate didn’t seem to be on my side, I don’t regret the journey at all and felt like I learned many invaluable lessons that I couldn’t have learned otherwise. Practically, though, as a major consequence of the essential unpredictability of eking out an existence in a foreign land, my idealized Australian itinerary changed drastically. Here is a summary map of where I actually traveled:

Probably the most noticeable difference between my idealized itinerary and my actual itinerary is the extent of the travels. Though I put over 15,000km on my campervan, I still only covered a fraction of the Australian continent. Major destinations like Queensland’s tropical north and the Outback’s red center were never reached. Travels to Western Australia and the Northern Territory were scrapped from the plan entirely.

Though I am disappointed at not being able to see such remarkable places, I’m not distraught over the lost opportunity. In conversations about my Australian trip, people often remarked that my journey was a ‘once-in-a-lifetime opportunity’. And, while making my plans for Australia, I took that sentiment to heart. I preconceivingly figured that I would never travel to Australia again—that this particular Australian trip would be my only chance to see places of world heritage value like the Great Barrier Reef or the Outback. Thus, I wanted to make sure I uncovered every stone Australia had to offer, so I could forever check the continent off my bucket list.

Abrasive reality—and sheer practicality—saw through my meager attempt to see everything in Australia. It is an impossibility to overturn every stone and leave nothing new to see in a country. Even if someone were to visit every square meter of a place, they would still have more to discover in the nooks and crannies. Such a person would still need to see the same things again, but from a different angle. Such a person would still need to spend more time in the country just to understand how the incessant elements of time and change affect a place. Fully seeing everything a country has to offer as a visitor is an absurd notion indeed.

As it so happened, I left many stones unturned in Australia. Though I wish I could have stayed longer and traveled more, I’m happy to say that I still have many reasons to go back to Australia in the future. Though I have no definite plans to revisit, I can see scenarios of returning soon to my much favored Hobart town for graduate school, or of returning only after many decades have passed as a grey-haired tourist. It’s also quite possible that I may never return to Australia again. But one things for sure: I never want to think of my stay in Australia as only a ‘once-in-a-lifetime’ opportunity.

The Passionate Lot

Doing so much travelling around lately, I have found it a great pleasure to go to unique little places where people’s passions are on display for any wayward visitor to share in. Lots of these places may be small, under-recognized, and out of the way of the main tourist haunts. Sometimes you just happen to stumble upon them, like a nugget of treasure. But wherever you have passionate, dedicated people, you’ll find the special places they have created to share. In addition to the individuality of the sights to see, it is the enthusiasm given by the creators of such places that makes visiting truly a momentous occasion.

Traveling between Sydney and Melbourne, I stopped at a few places off the beaten path and was pleasantly surprised at what I found. The places I visited stuck in my mind mainly because of the passionate and dedicated people that stood behind the projects. It was a joy to get to see the talents of others on display. Here is a sampling of some of these places I went:

- Rusconi’s Masterpiece, on display in Gundagai, New South Wales. Frank Rusconi was an Australian-born and European-trained sculptor, who dedicated his life to marble craft. Rusconi carved many magnificent sculptures and monuments throughout Australia, but perhaps he is most well-known for his marble masterpiece. Not just a sculptor by trade, Rusconi was a sculptor by hobby as well. Every day for 28 years, Rusconi would spend three hours at night working on his masterpiece castle of 20,948 individual pieces of Australian marble, meant to showcase the fine quality of marble on the Australian continent. Rusconi’s masterpiece was later donated to the public for all to see his craft.

- The Ned Kelly Animatronic Show in Glenrowan, Victoria. In Glenrowan, the location of infamous Australian bushranger Ned Kelly’s last stand, there is an animatronic re-enactment museum of the Kelly gang’s famous gun battle with colonial police. With a kind of dark Disneyland-ish aura, the experience takes visitors through a half-dozen rooms all depicting various stages of the Ned Kelly siege. In each room scenes were set up using mannequins and animatronics that tell the story; so involved is the realism that smoke will pour out of the burning hotel and Ned Kelly will make a surprise drop from the ceiling as he is hung by the police. With how well the show is put together, it might very well seem that the animatronic museum is new and uses advanced technology. But no, the 80-year old purveyor explained, he’s been working on the display over the last forty years. Though the old purveyor himself was slowing down due to age, he eagerly explained how his 20-year old grandson was keen on taking over the operation in the future.

- Cactus Country gardens in Strathmerton, Victoria. The cactus is not native to Australia, but it thrives very well in the arid climate nonetheless. Australia’s largest cacti garden, Cactus Country, is a testament to that fact, as well as a testament to owners Jim and Julie’s dedication. The seeds of Cactus Country were started in 1979, when Jim purchased his father’s cacti collection shortly before marrying Julie. Together they set upon creating the largest cacti display Australia has ever seen, and Jim and Julie continue to expand their 10-acre garden to this very day. I was very pleased to have run into Jim in the garden. After all, it’s not every day you can have a long conversation about cacti with a stranger.

Marble sculptures, animatronic bushrangers, and cacti gardens may not have a lot to do with each other intrinsically, but in this case they are all interests undertaken by passionate people. Some very talented people hide their talents and skills from the world. However, there is a passionate lot who put their skills on display for all to see, thus creating these places worth visiting. It isn’t always intentional either—passions pursued for their own ends will often become compelling enough to attract visitors. Meeting the people behind the work and experiencing their contributions is a real treat for the tourist-trap weary traveller. It makes travelling the backroads even more special.

A 25 Year-Old’s Retirement

Travelling around Australia in a van, I inevitably run into a different demographic of traveler doing basically the same things I’m doing. This demographic can be described as the older, retired lot who also live out of vans or motor homes and spend their time driving around and living like tourists. For some people, this is their dream lifestyle. They’ve worked hard all their lives to afford a retirement full of travel and leisure. Retirement is their final treat where they can enjoy the fruits of their labours free from the burden of work and outside obligation.

Perhaps retirement is wasted on the old. Wouldn’t it be better to travel when you’re still young and have the energy to see things? Wouldn’t travelling prove more fruitful if you still have the bulk of life ahead of you to be influenced by what you learn whilst travelling? For these reasons, I decided to take my retirement early. But instead of taking a retirement of pleasure and leisure, I am taking a retirement of travelling and learning. I wanted to ‘retire’ while I am still young and flexible, while my identity is still malleable enough to shape the person who I am becoming. If a great deal can be learned by travel, then why hold off those lessons until most of one’s life has passed?

But, another reason why I decided to retire early and to travel now is that I have a gut instinct that I will not be as inclined to travel later on in my life. Instead of always being ready to move on, I have a tendency to linger at a place that’s become familiar to me. Eventually, in the years to come, I sense that I will settle down into a place and a community where I can let my roots grow. Once I’ve settled into such a community, I won’t have the desire to journey as extensively as I am doing now. Of course travel will always remain a way to re-invigorate myself in day-to-day matters, but, I strongly suspect, my future will not be one where I continue to live out of a vehicle on a long ambling sojourn. Consequently, I feel I ought to be travelling now in my youth, while the wanderlust still churns strong inside me. In my old age, though, I project I’d like to live in one place. Life as a continual transient on the road will not be the life for me. Some people may also chose to retire in a different location from where they’ve worked their careers. Again, not for me. Once I find my community, I won’t leave it for a leisurely retirement elsewhere.

Yet another reason why I’ve taken an early retirement is that I’m not sure if I’ll be the type of person who will even want to retire. Inevitably, I feel very impassioned about the work that I do, and right now I’m on an extended quest searching for my life’s vocation. When I do ultimately engage in a line of work that I am passionate about, I doubt I’ll have the desire to leave it just because I reach a mandatory age. Instead, I will follow my vocation and continue to work towards the betterment of society and my community through my career. Life takes a lifelong commitment—and I’m not one to bow out for an early retirement. When thinking about the idea of old-age retirement, I am greatly motivated by stories of people who have lived their passions to the fullest extent of their lives. One story I find particularly inspiring is that of Carl Sharsmith, who had a 60-year long career as an interpretive ranger in Yosemite National Park, becoming the oldest active NPS ranger upon his eventual retirement at age 90, one year before his death. Some passionate people like Sharsmith just can’t be stopped, and I hope to be one of them.

These are a few of the reasons why I decided to take my retirement early. My gap year in Australia is not just a period of leisure and an attempt to postpone a career—it is an investment in the person I will be in the future. Soon enough, necessity will dictate an end to my early retirement and will see my entering of the workforce. But I look forward to this as well, like a person who just can’t stay away from a vocation which he loves.

Featured Image credit goes to the documentary This is Nowhere, which provides a perspective on the lives of nearly 3 million Americans who permanently live in motorhomes and camp in Wal*Mart parking lots

Small Town Country Australia

A view down Wynard Street, the main commercial avenue in Tumut, New South Wales

I’ve been passing through a lot of small Australian towns lately. Ever since leaving the tourist haunts of the coast and travelling inland, I’ve been encountering a new Australian geography. Up through the Great Dividing Range mountains and onto the western plains, Australian towns get comfortably country.

From the New England Highway to the west side of the Snowy Mountains, I’ve passed through towns more familiar with the rumble of a livestock truck than to the stamp of tourist feet. Populations in these towns may reach from a few thousand to a few ten-thousand—not necessarily tiny by Australian standards. Regardless of their size, however, these towns may be the largest settlement for an hour in any direction—and thus these small country towns serve as regional centers of commerce. Along the backroads and byways of rural Australia, a traveller will be rewarded with the very appealing character of the Australian Country town.

My experience of country towns is based on one I’ve spent a fair amount of time in recently: Tumut, New South Wales. Tumut, like other country towns, lies amidst a landscape of grazing, field crops, orchards, and timberlands. Roughly halfway between the major metropolitan centers of Sydney and Melbourne, Tumut sits 30 minutes off the main highway—and is largely bypassed by the hubbub of interstate traffic. With a population of just over 6,000, Tumut is the principle settlement in Tumut-Shire, in addition to being the largest town for at least an hour’s drive. Though Tumut may be nestled in the scenic western foothills of Australia’s highest peaks, the Snowy Mountains, tourist traffic remains light here largely due to hilly terrain and narrow town access roads.

Small country Australian towns like Tumut share a distinct geographic feel. At the heart of these towns runs the main street, lined with the town’s oldest and most elaborate buildings. Wide brick sidewalks traverse either side of the main street with store-front balconies and branching European street trees providing shade from the blistering country sun. The most prominent buildings along the main street just might be the hotels—in Australia, hotels are the place you go to hang out and drink a beer. Even in the small town of Tumut, there are no fewer than six hotels along the main avenue of business: The Commercial, The Oriental, The Royal, The Star, The Woolpack, and The Wynard. Banks, shops, public buildings, and churches complete the line-up of edifices on the main street. Further out from the main street, historic brick and stucco houses speak of early city residents who had a great sense of pride and importance in the place where they lived.Though individual businesses may change through the years, the turn-of-the-century street façade remains strongly characteristic of the country town.

In Australia, you go have a drink at the hotel. Being common sights in country towns, hotels have a pub on the ground floor and accommodation upstairs. Large, sweeping verandas provide much needed shade from the Australian sun.

The School of Arts Building, built 1891. In small towns, the ‘School of Arts’ was established as both a repository of books and a community meeting hall–an early multi-purpose community building.

Elaborate churches add architectural character to the town’s built environment.

Turn-of-the-century brick and stucco house, with a characteristic tin roof.

Scattered around the business district and residential streets of the typical country town is ample parkland, which lends an appealing openness and naturalistic feeling to the rural development. These parks provide shade, recreational opportunities, and amenities to resident and visitor alike. As a visitor to a new town, I often form my quality assessment based on the town’s parkland and amenities—for example, public toilets and electric barbecues are very appreciated. Civic buildings such as libraries are another important public resource that attest to a quality of life in a town, in addition to being very helpful to the traveller.

The physical landscape—the built environment—is just one aspect that is characteristic of the Australian country town. The other aspect is the cultural landscape. Though I originally only planned to pass through Tumut on my search for employment elsewhere, I’ve ended up staying for a week now. Having found no job leads further afield, I returned to Tumut to come up with an alternative plan, and I have stayed because I enjoyed the aura of the city. I’ve found the people to be particularly friendly here, and more apt to start a conversation with the town’s new stranger. This is especially true while I’ve been sitting outside the library after hours bumming wifi for my job search. One local man came right up and joined me on the bench I was sitting on, talking to me as if we’d meet long before. He really only came to the library for some half-smoked cigarettes in the ash-tray, but he wanted to greet the stranger as well. He gave me some advice for my job search, and then informed me that in a town like this, everyone will know your business by the time you leave. I guess that’s all part of the small-town life.

My one week in Tumut has given me a good sense of the nature of the town, and may be a good indicator of the character of the other country towns I’ve passed through along the way. With little in the way of tourist traps in Tumut, I’ve been living like a local instead. Daily, downtown Tumut is a bustling locale—at the shops and bakeries by day, and at the hotels by night. I’ve nursed a beer at one of the hotels, listening to live music from a nearby bluegrass band. I’ve been shown the river float along the Tumut river where locals go to cool off on hot summer days. My van radio has been tuned to the local radio station playing golden oldies and old-time country music. I’ve eaten local produce fresh from the weekend outdoor market. I’ve even watched part of a high-school cricket match, and I’ve seen the civic pride of the Tumuters as a large group volunteered their Saturday to pick up rubbish in the riverside park. All these little things I’ve seen and done here in Tumut add to the congenial character of this small country town.

The Tumut River, as seen from the Old Town Bridge. The name Tumut is derived from an aboriginal word meaning ‘resting place by the river’. The river is a favourite local hangout.

It’s not that only small country towns have the kind of charm I’ve described—it’s that I find it easier to perceive in a small country town, where the bright lights of international corporate business and the McMansions of suburbia don’t obscure the local identity. Large towns, urban centers—these too have their unique geographies and contingent of dedicated citizens who make their homes resplendent with civic pride. These are the same people who pass the love of their city onto the wayward visitor.

A view of Tumut from the highest point in town, showing the foothills of the Snowy Mountains

Moving On…

Sunset over the Sunshine Coast city of Mooloolaba

Tonight I sit reflectively on the spit as the sun sets, watching the distant foreshore of the Sunshine Coast as darkness falls and the city lights come on. Tonight is my last night here. Tomorrow I will move on.

Lychee harvest ended today. We had a celebration cookout under the veranda with all the workers, celebrating the achievements our labour accomplished. Afterwards we began our goodbyes to the crew we have known for a few short but intense weeks. “See you around,” say some as they leave the farm. “See you in Stanthorpe,” or “See you Tumbarumba” say others, gaily announcing their next planned destination, as if we expected to run into one another again. Joining the trend, I dismissed myself to the crew with “catch you in Batlow!”

But as I watch the sun set over the hinterland mountains, I contemplate why it is that I am moving on already. I didn’t even plan to be out here tonight—I had planned to stay inland to prepare for my upcoming departure. But something innate drove me to the coast. I just had to be here for one last night.

I have only been on the Sunshine Coast for a mere 31 days—longer than a visitor, but far short of being a local. I’ve just begun to know this strip of coastline and the lifestyle it affords. For a while, this place was my home. Why, I wonder sometimes, must I constantly be moving on right when I begin to know a place?

Australia, of course, is a different situation for me. Here I have no opportunity for permanency. I am no more than a long-term visitor, with a definite end-date for my time. My transiency is based out of the necessity of economics, continually chasing employment to support my holiday further. With immediate job opportunities on the Sunshine Coast having dried up, the promise of bountiful harvest labour now beckons me elsewhere. And too, I’ve created a busy itinerary for myself to see as much of Australia as I can—the breadth of my travels could not be reached if I do not continually move on. My own disinclination to linger beyond planned has left me a drifting traveller.

But I look onwards as the gleaming lights come on the high-rises above the beaches of Mooloolaba and Maroochydore. I wonder if I’d have the courage to deny my pre-conceived itinerary and continue to stay somewhere—merely because I enjoy the place. Would I brave enough to stop my relentless pursuit of places unknown (and potentially better) because here I have found something I’ve enjoyed?

I come from the generation sometimes characterized as ‘The Young and the Restless’. We move around easily from place to place, seeking localities suitable to our young, sociable lifestyles. No place is stayed at for too long if there is something better to be found. Myself, I always seem to be moving on from the places I have known out of a vital curiosity—an instinct—that there is something new, different, better out there to find. I feel convinced that if I stay too long in one place, I might not discover something else that fits me better. But I question my own logic. I’m too afraid to lose the illusory opportunity of something more promising that lies just beyond the world of the familiar.

I am one of a generation of cropped roots. Transiency describes my lifestyle, but I wonder why I always must be moving on.

Breaking Down in Australia

“I hope this old train breaks down

Then I could take a walk around

and see what there is to see”

—Jack Johnson in “Breakdown”

The inevitable backpacker van event has occurred to me: The Breakdown. It couldn’t have occurred at a much worse time than it did, late in the evening the day before I was supposed to start a long-awaited harvest gig early the next morning. But then the location was actually quite convenient. I’ve heard tales of backpacker vans melting down in the far remote outback, with no services for hundreds of kilometers. I happened to break down in the middle of suburbia.

This wasn’t the typical garden-variety breakdown either. This was what’s called the “catastrophic breakdown”. Upon inspection by a mechanic, it turns out the timing belt in the engine broke and warped the engine cylinders. Before this happened, I didn’t even know what a timing belt was, let alone its importance in an engine. It turns out, though, that the timing belt is the piece of equipment that keeps the engine’s moving parts in sync. A broken timing belt equals moving engine parts clanging against each other. It also equals a $3,000 charge for replacing the engine.

But when the timing belt snapped and Frank’s engine turned its last, we were quite fortunate to be on the busiest commercial highway along Queensland’s Sunshine Coast. Using Frank’s momentum, I managed to steer off the main road into a 7-11 parking lot. There I found myself ‘stranded’. Without my own set of wheels I was limited to where I could walk on foot—or to travel with the extensive bus transit network. Though I was without a vehicle, everything I needed was within walking distance on that main street—coffee shops, grocers, convenience stores, parks, car rentals, hostels, surf shops, furniture outlets, rug stores—and much more. I was even about a kilometer away from the repair shop (though I still needed the tow).

A long-time favorite musician of mine, Jack Johnson, holds a rather romantic notion of breakdowns, singing about taking the opportunity to get out and explore the world on foot instead of in high speed transit. But I’m doubtful Jack Johnson was daydreaming about breaking down in the midst of California-style suburban sprawl. Getting stranded nearly halfway between two of the Sunshine Coast’s major beach cities, the landscape has developed into a suburban dream of strip malls and Aussie big box stores that punctuate endless tracts of brick-fenced single-family homes. Not to mention that the wide, high traffic capacity streets and discontinuous sidewalks make pedestrian touring exceedingly difficult.

Personally, rather than looking at the opportunity for adventure that a breakdown affords (as I was more inclined to do when I was younger and broken down with friends), I more often view breakdowns as a hindrance. True, I’ve been through the stranded-from-car-trouble game a few times before. This resume of mine includes getting stuck in the ditch twice (in two different vehicles), and getting stranded after mechanical failure twice more (in an additional two different vehicles). In fact, on a long road trip I usually anticipate such car trouble to occur—and I’ll feel like I missed out on something if nothing goes wrong on a long trip.

Whether seen as a hindrance or opportunity, the breakdown does have its way of (forcibly) taking you off your own well-planned schedule and creating a new experience for you. Thus, when you face the inevitable breakdowns in life, do you dwell on the costs and inconveniences of the situation? Or do you use it as a path towards something you likely wouldn’t have done otherwise?

As far as Frank breaking down goes, it’s a mixture of both. No longer able to camp in my van while it’s in the repair shop, I had to take the only affordable and available accommodation I could find in a resort community during peak season. Sure my temporary accommodation’s among the lousiest of hostels I’ve ever stayed in, but I’ve gotten to meet many more people than I would have if I stuck to my van. And sure, the section of town I’m staying in now feels like Los Angeles sprawl, but there are many unique local eateries and enterprises hidden amongst the strip malls and traffic-clogged streets. I wouldn’t have noticed these things if I had merely driven through as a passerby. In the end, I’ll get to know a new area of Australia more intimately via foot. Plus, I’ll have walking access to some beautiful surf beaches every day after work.

Listen to “Breakdown” by Jack Johnson here: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Y4O7ufx9D_s

Yearning for the Open Road

Having landed in Sydney over three weeks ago, I’m starting to feel the urge to break out of the city and hit the open road to explore the Australian countryside. Getting started in another country has been a test in patience so far. My initally-planned one week in Sydney has stretched into nearly a month, due to various difficulties. Most recently is the slow wait for paperwork in the mail as I navigate the process of owning a motor vehicle in a foreign country.

Some of you may have seen my new Australian travelling companion on Facebook, Frank the campervan (note, I wouldn’t have chose the name for myself, but it’s bad luck to rename a vessel). Me and Frank met in Sydney and hit it off right away. We both yearn for the open road and love camping, so it was a good match. Frank is also a Starwagon—I love that he’s a bit celestial…

Me and Frank are making plans to go around Australia. Frank was born to travel and is already a veteran of some cross-country roadtrips. Of course we want to see everything the country has to offer. Here is a little sketch of what may take place over the next few months…

Our proposed route is to visit all of Australia over the course of a year (and maybe a little bit extra too). Overall, the route is about 21,000 kilometers, before any spontaneous side trips are taken. It’s an ambitious distance, but I had good practice in the United States before coming to Australia, driving over 30,000 kilometers in the course of my five month Western US road trip. Here is a month-by-month outline of my plan (follow along on the map—notice the route is color-coded):

November/December: Cherry Harvesting in New South Wales

January to April: Grape Harvest/Wine Making in Victoria

April to May: Berry or Vegetable harvest in Tasmania

June-August: The big holiday drive. Melbourne to Adelaide, through the outback to Australia’s red center, then Darwin to Perth following along the Indian Ocean.

September/October: Grapevine pruning in Western Australia

h

After October, my Working Holiday visa expires. If, however, the $21 an hour agricultural minimum wage puts me in a good financial situation, why not stay and play more?!? Here is a ‘bucket list’ of places I’d like to see in Australia:

- Cities to visit: Adelaide, Brisbane, Cairns, Canberra, Darwin, Hobart, Melbourne, Perth, Sydney

- Climb Sydney’s Harbour Bridge

- See a concert at the Sydney Opera House

- Watch a match at the Melbourne Cricket Grounds

- Go wine tasting in one or more of Australia’s wine regions: The Hunter, Murray, Margaret, or Barossa Valleys.

- See the attractions of Australia’s Red Center: Uluru, Kata-Tjuta, King’s Canyon, Devil’s Marbles

- See the dry Lake Eyre bed and other saline inland lakes

- Spend a night in the Outback

- Cross the Nullarbor Plain in Western and Southern Australia

- Travel Along the Great Ocean Road in southern Victoria

- Visit the wildlife reserve on Kangaroo Island

- Snorkeling along the Great Barrier Reef

- Sailing in the Whitsunday Islands

- Visit the tropical rainforests of Cape York

- Climb mount Koscuiszko, the highest point in Australia (2,228 metres)

- Embark on a 4-wheel drive adventure on Fraser Island’s Sand Dunes

- See the earliest multicellular fossils in the Ediacaran Hills in South Australia

- See the ancient Wollemi Pines in New South Wales

- Learn about aboriginal culture in an aboriginal village or in Kakadu National Park

It’s an ambitious course I’ve set for myself. But then again, that’s the way I like to live. Making trip itineraries is one of my favorite pasttime activities—but it’s all the more enjoyable when the trip plans are real instead of hypothetical. In the coming months, expect to see some outcomes of our travels!

Urban Nature

Sydney is a sprawling metropolis. But it’s also a beautiful city full of parks, greenspaces, and natural reserves. I find the interplay of the natural biological/ecological element in built-up environments fascinating. It’s a niche scientific field known as Urban Ecology, but I like to think of it more like Urban Nature. Here is a smattering of some natural sights I’ve been intrigued by around the city so far:

jfg

Let’s start out with the base…geology of course. Sydney is built upon a vast expanse of sandstone. Add the weathering action from the maritime climate, and this sandstone erodes into numerous cliffs that expose the natural patterning of the rock. Early Sydnians made use of the sandstone, using convict labor to carve steps into the soft rock and quarrying stone for Sydney’s elegant public buildings. (Images: grottos of eroded sandstone pockets; contrast of light rock and dark staining from running water; color patterning; color patterning)

jfg

I wouldn’t be true to myself if I wasn’t fascinated by the new plants I’ve seen here. They may be cultivated as landscape plants, but their wild beauty exists nonetheless. (Images: Fig Tree growing mass of adventitious roots; succulents growing on sandstone cliffs; Jacaranda Tree in full purple blossom, row of unidentified trees in a park)

jfg

One can’t walk around an urban park in Sydney without seeing the ubiquitous Australian Ibis. With its long curved beak and bald black head, it’s a quite different looking bird than what is common in the States. Interestingly enough, the Ibis wasn’t common in urban areas until a series of droughts in the 70’s and 80’s pushed the Ibis into the cities. Though a species native to Australia, its decline in its native habitat and rapid increase in urban areas has led to questions as to whether it’s an endangered species or a pest.

jfg

Another ubiquitous bird in the city is the Common Myna. Unlike the Ibis, the common myna is not native to Australia, and its status as a pest is unequivocal (it is recognized by the International Union for Conservation of Nature as one of the top 100 invasive species). The urban environment, however, provides the ideal habitat for these birds. Adapted to life as a scavenger in woodland environments, the features of a city—the abundant buildings for nesting, open sidewalks for foraging, and plentiful food scraps—provides an ideal home.

jfg

Ferns, being one of the most ancient types of plants, are able to thrive in harsh environments—both natural and urban. They grow wherever a crack in infrastructure provides a small foothold and traps enough moisture to drink. Here these ferns find a home similar to a sandstone cliff in the seaside dock and decaying brick wall.

The Cultural Exchange

I’m in Australia on what’s called a ‘Working Holiday’ visa. The working holiday visa program is a special arrangement between two countries that allows young residents (under 30) of one country to easily obtain a visa with working privileges to the other country. One of the goals of this visa program is to promote cultural exchange between the two participating nations by allowing up-and-coming youth to stay and work in a partner country for an extended period of time. I’m taking it as my homework to promote this cultural exchange between the United States and Australia. Though our cultures are very similar at first glance, I’ve come up with a list of things each country can learn from each other.

What the United States can learn from Australia:

- The advertised price is the price you pay. Taxes (i.e. the sales tax, or what’s called the GST General Service Tax in Australia) are included in the advertised price. No more hidden taxes or surprise charges at checkout time. It seems to be most fair that the price you see is the price you pay. As an American used to forking over just a little bit more cash when buying something, I still feel a little guilty at checkout, like I got away without paying for something.

- Get rid of the penny. I love the penny, but it’s time has come. Nowadays the penny is worth more in nostalgia than practicality. Whereas Americans enjoy advertising things for $X.99 and calculating taxes and transactions precisely down to the last penny, Australians are fine with rounding things to the nearest nickel. It’s easier that way, especially when taxes are already included in the advertised price.

Australian coinage, showcasing it’s unique fauna on the reverse sides of the coins

- Breakfast Cereal: America may be the envy of breakfast cereal variety, but the Australian cereal aisle was built for the health lover. No Froot Loops or Lucky Charms to be found in this country. Instead, Australia is famous for its health cereals, the more wheat and bran you can pack in the better. Most notable of all is Weet-Bix: the driest, most sawdust like breakfast biscuit ever engineered, but oh so tasty! Plus, in a feat of near-magic, a few Weet-Bix can absorb an entire bowl of milk.

Weet-Bix: “Every Aussie is raised a Weet-Bix Kid”

- Little cars and trucks can get the job done. You don’t need to make up for anything by driving a big truck. A compact van or flatbed sedan will work just fine to get the job done. Plus, compacts will help you maneuver into those tight Australian travel lanes. I’ve really been pleasantly surprised here in the city at how compact and efficient the vehicles are. No semi-trucks (at least in Sydney), and the biggest vehicle around is the size of an American mini-van.

What Australia can learn from the United States:

- Smoking is not healthy. So many people in Australia smoke compared to the States, and it’s not stigmatized as a lower-class activity either—in fact, most smokers seem to be wearing business casual. Whereas America has kicked its smokers to the curb, in Australia smokers have free range to roam—but as of recent they have to now be outside. Ashtrays aren’t really a thing here either. Throw your butts straight to the ground, and don’t worry because it’s someone’s job to sweep those butts up later. I would have thought that the cigarette cartons with lovely pictures of gangrenous limbs and mouth cancer would have been a deterrent to light up, but I guess not…

- Bike Culture: With terrain as flat as a Midwestern cornfield and weather as lovely as southern California, Sydney could be a biker’s paradise. Except that the bike culture is nearly non-existent here. As a biker, I’d be absolutely terrified to ride in the narrow, congested lanes of traffic—especially seeing how Sydney-ians drive. Though Sydney has converted some traffic lanes into really nice and safe bike lanes, no one seems to be using them. I’m thinking a big dose of Portland-style Bike Culture would provide the needed fix. It’s a two-way street though: the United States should take a cue from Australia and make bicycle helmet use mandatory.

Bike infrastructure in Sydney: Great when it’s there—it’s just not there in many places.

- Raincoats: With a week of Seattle winter-like weather recently behind Sydney, I’m beginning to think that people in Australia don’t know what a raincoat is. Sure Australia may be the driest inhabited continent, but it still rains here. However, the preferred choice of rain-protection seems to be massive umbrellas instead of rain jackets. A rainy day in Sydney is a hazardous place for a tall person forced to navigate the sidewalks of bobbing umbrellas bustling at perfect head-height.

- Yellow Centerline Road Stripes: All road markings in Australia are done with white lines, as opposed to America’s system of using yellow lines to separate oncoming traffic and white lines to separate traffic travelling in the same direction. Although it seems like a small detail, this is probably the most important factor in why traffic on the left-hand side of the road hasn’t seemed odd to me. With only white markings, every street in the city looks like a one-way street. I suspect this might cause some troubles when I start driving in Australia later…

I’m still ambivalent about…

- The Walk Signals: Green Walking Man and Red Stopped Man. It makes somewhat more intuitive sense than other signals—unless you’re color blind. The jury is still out on which signal is optimal. But one thing for certain is that Australian walk signals seem to favor the flow of traffic. A walk down the street results in a fair amount of time stopped at the crosswalk waiting for the signal to change, even when cross-traffic is stopped as well.

Walk. Don’t Walk.

- Australian Urinals: They are a floor-trough style with a waterfall flush. Fun to use, because it feels like I’m peeing on a wall of cascading water, but it definitely offers less privacy than single-user urinals. Also, although many urinals are flushed with reclaimed gray-water, the constant waterfall flushing still seems wasteful.

- Male and Female Toilets: The proper name of the room to relieve yourself here is the toilet—straightfoward, but less tactful than the American usage of ‘restroom’. Also, the gendered toilets are labeled by the biological sex of ‘male’ and ‘female’ instead of by the gender identities of ‘men’ and ‘women’. Biologically correct, but it seems out of sync with contemporary conversations about gender identity and restroom use.