Cherry-conomics

Over the course of the cherry season, I harvested on four different farms and worked for three different labour contractors (I was never directly employed by the cherry farmers themselves. Rather, most farmers hire contract crews for the duration of the harvest season. The contractor hires the harvesters and manages their pay, freeing the farmer to only coordinate with the contractors). Thus, I’m not an expert on cherry economics, but I do have an idea of how a few different farms and contractors operate. From my experience, here’s some basic statistical explorations and speculations about “cherry-conomics”:

I was in Orange, New South Wales for the cherry season for 23 days. I only worked for a total of 17 days though, because some days no cherries were ripe, some days it was raining, and some days I just needed a break. Over the course of my tenure, I earned $1,936—that equates to $113.88 per day I worked, or $84.17 per day I was in Orange. For days I did get to work, there was a great range of wages earned—from a low of $35 to a high of $185. A lot of this wage variability depended on the hours worked. Not every day of work was a full day. Some days were short because all the ripe cherries were quickly picked. Other days were cut short when noon rain showers rolled in. Conversely, other days were long because the farmer wanted to finish harvesting a certain variety on that particular day. As a result, on any given day I picked cherries from three to twelve hours.

As far as compensation, I was paid on a piece rate. The Australian agricultural minimum wage is $21 per hour, but employers are also allowed to pay workers on an equivalent piece rate. The piece rate is calculated based on the amount of fruit an average worker can pick in one hour to equal the minimum hourly wage. From the different farms and contractors I worked for, I surmise that the equivalent piece rate is about $1.10 per kilogram of cherries picked. A well-seasoned cherry picker can easily exceed the hourly minimum wage. As a novice, though, I had trouble matching that rate. Some days, when the cherries being harvested were large and plentiful, I could earn upwards of $25 per hour. However, over the course of the whole season, I estimate that I earned an average of $15 to $17 per hour. Though I was disappointed I couldn’t meet the equivalent minimum standard, when compared to the $10 per hour I was making in the States, I was quite happy with the wages.

(As a side note, at the going rate of $1.10 per kilogram, I would have picked an estimated 1,760 kilograms of cherries, or about 3,880 pounds).

That’s how I fared statistically as a worker. The other side of the equation is the profit from the cherries.

From prices I’ve seen in the grocery stores, a kilogram of cherries will sell for about $12 (note that this is for fresh local cherries, not export cherries or process cherries). Of this price, the harvester will get somewhere around 10% of the retail value. The other costs of the cherries include the growing costs, transportation costs, and retail markup, of which I have no idea about costs. But everyone gets a cut on the cost of cherries as they go through the worker to the labour contractor, to the farmer, to the packer, to the distributor, and then finally to the retailer.

However, I was able to learn a little bit about the cut of the cherry price that labour contractors get. I’ll use the example of the farm I worked at where I learned the most. At this particular farm, cherries were harvested in 8-kilogram ‘lugs’. My contractor negotiated with the farm to pick these lugs at a cost of $13.75. Of this $13.75, I was paid $10 to pick the 8-kilogram lug. This equates to $1.25 per kilogram picked (note: at another farm I was only paid $1.00 per kilogram, but since the fruit was larger and easier to pick, I still earned better money). Thus, for every lug of cherries I picked, I earned my contractor $3.75. Since I picked 84 lugs of cherries with this particular contractor, I earned him $315 over 10 days of employment with him. As a worker, I would have liked to earned that extra $3.75 per lug. But, when middlemen take their cut as contractors, the wages payed to workers take a cut.

And finally, one speculation on the cherry business. At this particular farm with the 8-kilogram lugs, an average tree would yield six lugs, or about 48 kilograms of cherries (106 pounds). At an average retail value of $12 per kilogram, each cherry tree would produce around $576 worth of fruit annually. Multiply this amount per tree by the hundreds to thousands of trees in an orchard, and the value of just a few acres of fruit trees becomes obvious.

Life is (not) Always a Bowl of Cherries

I like to think of fruit picking as a gold rush of sorts: Boom or Bust.

The promise of a ‘boom’ is the reason a lot of foreign workers (including backpackers) and Australian citizens pick fruit—there is good money to be earned. A good harvest season can be a boon to the workers, as thousands of dollars of fruit can be picked in just a few weeks. The backpackers will use this money to finance an extended holiday, some Australians use the windfall to support a semi-working lifestyle, and other foreign workers will save the money to send back home. So far I’ve heard numerous tales of people picking up to $500 worth of fruit in one day—and over the cherry season I worked with a guy who regularly picked $300 worth of fruit per day.

But the harvest season can also go bust. The picking can be there one day, but then suddenly disappear due to myriad circumstances. Thus, the biggest ‘bust’ with fruit picking is the uncertainty of the labour itself. Frankly, the fruit doesn’t care about whether there are workers ready and waiting to harvest; the fruit ripens at its own pace, and is indifferent to becoming overripe as well. Likewise, the weather doesn’t care about harvest season either. Unfavourable weather can scrap a day of picking even when the fruit is perfectly ripe. Finally, market factors are also at play. If there is no market demand for fruit at the time, the crop will remain unharvested even if all other factors are favourable to harvest. Thus, a worker’s schedule is at the behest of many outside factors, making a regular work schedule somewhat of a fantasy. Willing workers end up waiting around for the fruit to ripen, the weather to clear, or market demand to kick in. But once harvesting conditions become ideal, it literally pays to be there. And if you aren’t ready in that moment, you’ll miss out on the boom.

The locality where I harvested cherries, Orange, New South Wales, was no exception to the fickleness of harvest labour. With a delicate crop like cherries, the old farmers’ nemesis of foul weather wrecked its havoc. Orange had a particularly wet summer harvest season. With too much rain, ripe cherries will swell and split. Additionally, if the cherries stay wet for too long, mold and fungus will attack them (this later problem, I learned, is a big enough concern that it justifies the cost of cherry farmers flying a helicopter just above the tops of the cherry trees in order to blow the excess water off).

With periodic days of steady rain (and a hailstorm) during the harvest season, things were going pretty rough for the Orange cherry farmers. Already I had to switch farms after an isolated hailstorm destroyed that particular crop I was harvesting. Then for a while things were going good, as the cherries were ripe, the weather was clear, and the cherries were in demand. But, 2½ days of heavy drizzle around Christmas time temporarily ceased harvest operations and seemed to spell the end of cherry season in Orange. Fortunately, in spite of the rain (and perhaps with the help of the farmers’ helicopters) it seemed as though the cherries survived. Full-scale harvest operations resumed after the rain for a couple of days, and there were still enough cherries remaining on the trees for two weeks of solid work. Conditions were seeming good once again.

Conditions were good, except that in order for the farm to sell the cherries, there needed to be a willing buyer for the fruit. Thus, one day after picking operations at the farm resumed full scale, the cherry harvest ended once again. The buyer of the cherry farm’s fruit, a cherry packer based in Melbourne, suddenly refused to buy the fruit. After sorting out the split and moldy cherries, the Melbourne packer found that it didn’t get enough quality fruit to make it economical to keep buying from the farm. Thus, as soon as the farm manager got the call from the packer with the news, the farm manager had to go around the orchards telling all the workers to drop immediately everything they were picking. With no buyer for the cherries, there would be no money coming into the farm to pay the workers for any further picking. Thus, cherry season ended a second time, for economic reasons. This occurred in spite of acres of trees left to harvest all containing good fruit mixed with the bad.

But, it turns out cherry season wasn’t over after all. The farm, as expected, did not want all of its fruit to rot on the trees. To recoup operational costs, the farm needed to salvage as much cherries as they could. So the farm negotiated a lower cost of fruit to their packer, and picking operations resumed yet again. The resumption of work was bittersweet news for the pickers. Even though there was work to do again, the lower value of the fruit meant that each worker would now get paid less for the same amount of work as before. But, when the choice comes between low paid work and no work at all, there will always be those who have no choice but to take the lower-paid work.

My experience working the cherry harvest in Orange highlights the biggest downside to this boom-and-bust cycle of fruit harvest labour: the uncertainty. This labour is not a 9 to 5 weekday job. Instead, you have to live your life around the unforeseeable schedule of work. You either end up working all the time for a short while, or you end up with no work to do for days on end. When the picking is there, you have to be able to take it in order to make your living. The fruit won’t wait for you. And even if it did, other people would pick that fruit before you to earn more money for themselves.

For these reasons, harvest labor is well suited to the flexible itinerant backpacker or the handful of professional Aussie fruit pickers who decided the lifestyle worked for them. One can’t place a schedule around the fruit harvest season, nor can one really plan that much around it. And, unless you live in a really rich and diverse agricultural area, work will usually not be year-round. As it happens, such uncertainty of the economic viability of harvest labour makes it very difficult to live traditionally or with much certainty.

In Australia, the bulk of the harvest labor seems to come from individuals who find the nomadic and uncertain agricultural work accommodating to their lifestyle. Yet, I have met many foreign guest workers and Australian residents who have had to pick fruit as their main means of economic survival. As unskilled labor with plenty of easy jobs to get, fruit harvest labour may sometimes be all people have available to them. This situation isn’t limited to Australia either. I’m thinking of all the individuals in the United States alone who do harvest labour for their livelihood. Under such employment circumstances, it’s extremely difficult to build a traditional lifestyle off of the uncertainty—such as challenges of instability from moving around to find work, and supporting a family on variable harvest employment.

One thing I will take away from this experience is a greater sympathy for the basic challenges of individuals who have to do agricultural labour as their economic means of survival. Somehow there has got to be a way to make it easier for such people to live.

Life in a Migrant Worker Camp

My alarm goes off at 4:45 am. I don’t need to get up that early. I just like to be one of the first ones up before the flow of activity starts in earnest. Outside, the land remains dark, but twilight is imminent enough to walk around in the dim light unaided. The first streaks of crimson light have already appeared in the far reaches of the eastern sky. The sun will make its way above the horizon shortly.

I crawl out of my tent into the cool morning air for the start of another day. The cold from the night will linger still for a while longer. A few early risers mill about in the murky dawn. Rows of vans and tents line the fields of this makeshift migrant worker camp at the Orange Agricultural Showgrounds. Life in the backpacker camp is about to begin a new day.

Brushing off the sleepiness from my eyes, I slowly start stirring about, preparing my body for the day ahead. Sore, blistered fingers gingerly make their way down my second-hand button-up work shirt. A quick rinse of the face in the mobile restroom unit washes the remaining sleep out of my eyes.

I make the short walk from my tent to the backpacker kitchen, if the facility even deserves that moniker. The kitchen is located inside an open-air animal barn, the sign labelling the building’s use for ‘dairy goats’ has been temporarily taken down and now lays solemnly against the wall. In place of showground dairy goats, the backpacker’s makeshift kitchen has sprung up. An odd assortment of worn tables and mismatched chairs are scattered around the trampled dirt floor in what can only be described as the unwanted leftovers of a bankrupt thrift store. On the left hand side of the building sits the kitchen area—a row of second-hand refrigerators, a lone sink draining directly to the lawn outside, and a folding table filled with a hodge-podge of small appliances.

I brought my own bowl and spoon for breakfast. Around here, dishes face a grim future. Lying shattered on the floor amidst the cigarette butts, unwashed on a table for days on end, or disappeared without a trace. My morning breakfast consists of a cut-up banana and seven Weet-Bix biscuits with milk (or yogurt, if dumpster-diving in town has proved successful). A hearty breakfast like this has proven to keep me satiated for a full 12-hour day of cherry-picking, provided enough cherries are snacked upon during the day to keep energy levels topped off.

I wash my bowl in the sink and head back to my tent to change into my work boots. Activity at the camp has picked up considerably. Rank-and-file cherry pickers mill about. By now it is well past light enough to pick cherries. Around 5:30 am, the first contingent of workers departs the camp, going silently off to unknown orchards in the countryside. Soon I will follow in my own van to see what type of harvest is in store for the day.

***

Who knows what goes on during the day in this camp when most people are gone working? Those who spend their days on the Australian harvest trail are not cognizant of such endeavors.

For, harvest work can come all at once, or not at all. Those lucky enough to have work for the day eagerly take the opportunity to earn whatever money they can. Around here, money earned is used to finance an extended period of holiday in Australia. Those for whom work wasn’t available, the whole day remains for enjoyment. Thus, on any given day there is a lot of hanging around in camp. A soccer game may break out in the field. The make-shift will kitchen gradually fill in the afternoon with workers, watching a movie or playing cards.

***

A day of cherry picking can last only for the morning, or well into the evening. With the amount of work varying day to day based on any combination of the number of workers, amount of ripe cherries, and the weather conditions, the amount of harvest work available is always in flux. In any case, the workers will eventually return to their seasonal camp once more, where evening activities are much more conspicuous than the morning lull. The evening hours sees the camp kitchen full and boisterous. The upwards of 100 people living and working here are unwinding from their days and celebrating the night. Clusters of people are scattered about akin to the furniture. The handful of young Australian pickers sit on a couch drinking beers and alternating practice on a skateboard. A group of young but mature Germans stick quietly to themselves, making and eating their dinner in hushed tones. The French are the most prolific and animated demographic here. They cluster in large groups all over the kitchen area. Soon the French will start their nightly session of Goon Pong. It’s the game of choice at camp, played exactly like beer pong, but the beer being substituted for Goon—Goon being the Australian slang for any form of cheap alcohol. In this case, the Goon of choice is boxed wine, but taken out of the box so that the internal wineskin can be slung around person to person.

All signage put up by the Showgrounds administration, as well-intentioned as it was meant to be, is disregarded by the backpackers. The harvesters roll their own cigarettes and smoke in the kitchen under the no-smoking signs. The butts are discarded on the dirt floor in jest. Dishes are used and left dirty, and half-eaten food litters the tables when the distraction of drinking games becomes too much. Activity will continue long after the posted hours of 10pm, unless the neighbors across the street call management to shut things down

The camp kitchen at night is not the place for me. I make an easy dinner with the limited utensils and eat it among some even-tempered fellow harvesters I have meet during my time here. We relax, we talk smack, but under no circumstances do we talk about cherries. After a while of hanging out, it has come time for me to leave.

As I walk back to my spot on the edge of camp in the mottled lamplit dusk, cheers from the Goon Pong game erupt. Another game has just ended in an apparently spectacular fashion. I settle into my tent between 9 and 10 pm, tired from the day and in anticipation of better cherry picking the next morning. As I get comfortable under my blankets, I pull out my book to read. I’ll be dozing off in a matter of pages. Clamorous uproars continue to emanate from the camp kitchen, fading out of cognition as sleep encroaches upon my mind. The cool air of night begins to settle over the Showgrounds.

And I Live in a Van…

Having left the luxuries of the big city and the comforts of a hostel bed, I have moved on into the Australian countryside in order to earn my pay to extend my stay. And I live in a van… (sorry, but it’s not down by the river).

The campervan culture is very conspicuous in rural Australia, as all the foreign workers (that is, the working holiday makers) flock to agricultural towns in anticipation of the fruitful harvest season.

I bought my van and have joined the ranks of itinerant fruit pickers. Just wanted to introduce everyone who is curious to my new digs.

This is Frank the campervan. He’s a 1997 Mitsubishi Starwagon. At that age, he’s developed quite a number of quirks, but the most important thing is that he’s reliable and a hard worker…sort of like me!

Here’s a look at my gourmet kitchen. Built-in sink, mini fridge, lots of storage…

Here’s my grand banquet dining room and home office…

Here’s the master bedroom. The table folds down and converts to a bed at night. Comfy.

And finally, here’s what I look like driving the van. Australian driving is a daily feat of pure determination!

The Beauty that Surrounds You

It’s a common question that gets asked when travelling.

“Where are you from?”

Answering the friendly chatter, you state where your home is.

“Ah,” muses the asker in polite conversation, “it must be beautiful there.”

As often as we hear this archetypal dialogue, we may not feel like the place we’ve come from is beautiful. But maybe it is. Maybe we ourselves just fail to see the everyday beauty that surrounds us in the places we come from.

As a traveler, visiting places for the first time, I am often struck by the beauty of the places I am venturing. It’s that initial shock—that sensation of something new and different being experienced—that gives the visceral feeling that this place is uniquely beautiful. The novelty of traveling to places unknown draws specific attention to the beauty held within.

In the five-week course of my Australian travels, I have repeatedly been struck by the beautiful landscapes I have seen, ranging from the inner wilds of Sydney itself to the untamed bush on the edge of civilization. Continually I’ve been awed by how different—and wild—and beautiful—it all seems. I feel like the people who live in Australia must daily be astonished by the beauty that surrounds them. How could where I come from even begin to compare?

After a pause, I answer the question posed by my fellow traveler.

“Yes, I suppose it is beautiful where I come from.”

Why do I seem to disvalue the place where I come from, as if all these other locales in the world are more scenic and more beautiful places to be? Is it perhaps the familiarity of where I come from which desensitizes me to the geography of my own homeland? For, where I come from is the known, the familiar, the common, the quotidian. The landscape of home becomes a daily occurrence, one that loses saliency in the day-to-day routine. As the backdrop of daily life, one’s homeland doesn’t seem to invoke that sense of witless awe or grandeur that one may experience travelling to a new place for the first time. In a sense, we don’t appreciate the magnificence of the places we come from to the degree that a traveler would.

But where I come from is beautiful. I know it. I can remember it. There are certain aspects of where I come from that I love—and I’ve come to realize how beautiful they are based on how I miss them. I long for that big lake I’ve known since childhood, that expanse of freshwater so vast that you can’t see across it. To this day, whenever I encounter a body of water I can’t see across, this feeling of nostalgia is invoked within me, reminding me of how beautiful that lake is to me. Similarly, a forest just doesn’t seem right unless it’s composed of northern hardwoods. For all the grandeur I’ve seen of the towering Coast Redwoods or the monumental Giant Sequoias, the prosaic humble hardwoods hold a spot in my heart—one of that comfortable embrace of a broadleaf canopy overhead. And the smells of the forests too—and the visceral sensations! That watery hug of the humidity on your skin on those sticky summer nights. That glorious smell after a fresh summer rain when the plants are green and the worms come out. The soothing sounds of crickets at night and the neurotic blinking of the fireflies. All these things about my home I’ve missed. These things are what home feels to me, and together they form a beautiful image in my mind. Sure, my homeland may not have the imposing majesty of Uluru-Kata Tjuta National Park, or the international status of the Great Barrier Reef, but it is beautiful nonetheless. It is the beauty of a place unique to itself.

Environmental historian Bill Cronon, in his profound but controversial essay “The Trouble with Wilderness,” reminds us that conservation starts at home. We need to start seeing the beauty—i.e. the wilderness—in the places we call home. Travelling to the wild and scenic fringes of the world may invoke in us a sense of grandeur worth protecting, but we need to learn from these sentiments and bring them home to value and protect the places we know as home—whether home is in the central city itself or in the uncouth fringes of the urbanized world. As Cronon puts it:(emphasis mine, and I’ve substituted the word ‘beauty’ for ‘wilderness/wildness’ as a synonym in two places)

“Wilderness [Beauty] gets us into trouble only if we imagine that this experience of wonder and otherness is limited to the remote corners of the planet, or that it somehow depends on pristine landscapes we ourselves do not inhabit. Nothing could be more misleading. The tree in the garden is in reality no less other, no less worthy of our wonder and respect, than the tree in an ancient forest that has never known an ax or a saw—even though the tree in the forest reflects a more intricate web of ecological relationships. The tree in the garden could easily have sprung from the same seed as the tree in the forest, and we can claim only its location and perhaps its form as our own. Both trees stand apart from us; both share our common world. The special power of the tree in the wilderness is to remind us of this fact. It can teach us to recognize the wildness [beauty] we did not see in the tree we planted in our own backyard. By seeing the otherness in that which is most unfamiliar, we can learn to see it too in that which at first seemed merely ordinary. If wilderness can do this—if it can help us perceive and respect a nature we had forgotten to recognize as natural—then it will become part of the solution to our environmental dilemmas rather than part of the problem.”

We need to learn—or maybe relearn—to appreciate the wonderful world that daily surrounds us. Travelling to the wild and pristine parts of the world can invoke the sense that such places are beautiful and worth our protection. But also, in seeing the innate beauty in a landscape that is so unfamiliar, we can learn to see again what is spectacular and worth protecting about the stage of our daily lives—a stage that sometimes seems to become just the merely ordinary. It doesn’t take a particularly observant eye to see the beauty in one’s surrounds; it just takes a perceptive mind to recognize it again when it becomes commonplace. I didn’t need to go to Australia to see beautiful landscapes—although admittedly it is much easier for me to sense it here. Instead, beauty abounded as well in the home I left behind.

Maybe sometimes we need to remind ourselves of the beauty that surrounds us. Maybe we should try and view the places we come from with the eyes of a traveler.

(Photo Note: Three Sisters Formation, Blue Mountains National Park, New South Wales, Australia)

In a Land without Thanksgiving

Today, as many Americans gather with family and friends around a dinner table to partake in the traditional late November Thanksgiving feast, I find myself in a country that does not celebrate a similar national holiday. From its North American origins, the idea of an official Thanksgiving holiday never spread to mainland Australia. Yet, even though I miss the traditions of the holiday as I stay in a land that doesn’t celebrate Thanksgiving, I still find myself having a lot to be thankful for:

- Support from Family and Friends. I am grateful for the encouragement to travel that I have received—and continue to receive—from those at home. But I also realize that there are people out there who are lonely this holiday season or who don’t receive support from others. May we reach out to those who are alone.

- The Ability to Travel Freely. I am thankful for the ability to freely and easily travel internationally without fear of danger, and I’m also thankful that people from other nations are able to travel so as to create cultural interchange and understanding among different nationalities. But I realize that there are people in the world who can’t freely travel from or within their own country, or refugees who are forced to travel from their homes, or people whose safety in daily life remains uncertain. May we create a global society that encourages travel and cultural exchange, embraces refugees, condemns violence and hatred, and is understanding of other cultures.

- The Financial Security to Delay Employment. I am thankful that I was able to have employment throughout the duration of my education, allowing me to save money and create the financial security that allows me to delay future employment and travel instead of working. But I realize that many people today remain financially insecure, cannot find a job, or cannot afford the luxury to not work. May we create a civic society where any worker can get paid a fair living wage, social welfare looks after those who are disadvantaged, and the youngest generation is not burdened by educational debt.

With today’s traditions of thanks and gratitude, take a moment to reflect on the things in your life that you’re thankful for. Also consider how we might craft a society where more people will have more to be thankful for in the Thanksgivings to come.

Yearning for the Open Road

Having landed in Sydney over three weeks ago, I’m starting to feel the urge to break out of the city and hit the open road to explore the Australian countryside. Getting started in another country has been a test in patience so far. My initally-planned one week in Sydney has stretched into nearly a month, due to various difficulties. Most recently is the slow wait for paperwork in the mail as I navigate the process of owning a motor vehicle in a foreign country.

Some of you may have seen my new Australian travelling companion on Facebook, Frank the campervan (note, I wouldn’t have chose the name for myself, but it’s bad luck to rename a vessel). Me and Frank met in Sydney and hit it off right away. We both yearn for the open road and love camping, so it was a good match. Frank is also a Starwagon—I love that he’s a bit celestial…

Me and Frank are making plans to go around Australia. Frank was born to travel and is already a veteran of some cross-country roadtrips. Of course we want to see everything the country has to offer. Here is a little sketch of what may take place over the next few months…

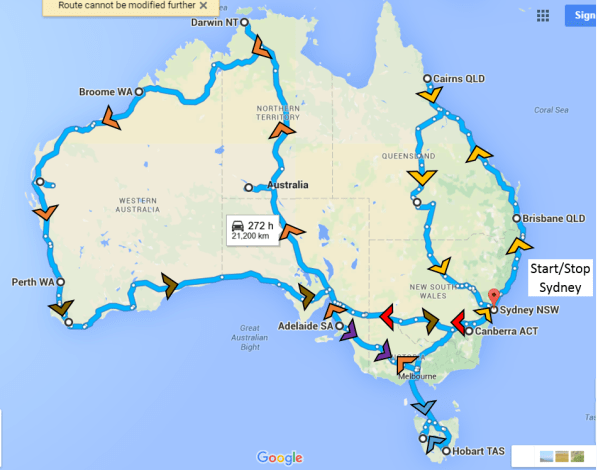

Our proposed route is to visit all of Australia over the course of a year (and maybe a little bit extra too). Overall, the route is about 21,000 kilometers, before any spontaneous side trips are taken. It’s an ambitious distance, but I had good practice in the United States before coming to Australia, driving over 30,000 kilometers in the course of my five month Western US road trip. Here is a month-by-month outline of my plan (follow along on the map—notice the route is color-coded):

November/December: Cherry Harvesting in New South Wales

January to April: Grape Harvest/Wine Making in Victoria

April to May: Berry or Vegetable harvest in Tasmania

June-August: The big holiday drive. Melbourne to Adelaide, through the outback to Australia’s red center, then Darwin to Perth following along the Indian Ocean.

September/October: Grapevine pruning in Western Australia

h

After October, my Working Holiday visa expires. If, however, the $21 an hour agricultural minimum wage puts me in a good financial situation, why not stay and play more?!? Here is a ‘bucket list’ of places I’d like to see in Australia:

- Cities to visit: Adelaide, Brisbane, Cairns, Canberra, Darwin, Hobart, Melbourne, Perth, Sydney

- Climb Sydney’s Harbour Bridge

- See a concert at the Sydney Opera House

- Watch a match at the Melbourne Cricket Grounds

- Go wine tasting in one or more of Australia’s wine regions: The Hunter, Murray, Margaret, or Barossa Valleys.

- See the attractions of Australia’s Red Center: Uluru, Kata-Tjuta, King’s Canyon, Devil’s Marbles

- See the dry Lake Eyre bed and other saline inland lakes

- Spend a night in the Outback

- Cross the Nullarbor Plain in Western and Southern Australia

- Travel Along the Great Ocean Road in southern Victoria

- Visit the wildlife reserve on Kangaroo Island

- Snorkeling along the Great Barrier Reef

- Sailing in the Whitsunday Islands

- Visit the tropical rainforests of Cape York

- Climb mount Koscuiszko, the highest point in Australia (2,228 metres)

- Embark on a 4-wheel drive adventure on Fraser Island’s Sand Dunes

- See the earliest multicellular fossils in the Ediacaran Hills in South Australia

- See the ancient Wollemi Pines in New South Wales

- Learn about aboriginal culture in an aboriginal village or in Kakadu National Park

It’s an ambitious course I’ve set for myself. But then again, that’s the way I like to live. Making trip itineraries is one of my favorite pasttime activities—but it’s all the more enjoyable when the trip plans are real instead of hypothetical. In the coming months, expect to see some outcomes of our travels!

Urban Nature

Sydney is a sprawling metropolis. But it’s also a beautiful city full of parks, greenspaces, and natural reserves. I find the interplay of the natural biological/ecological element in built-up environments fascinating. It’s a niche scientific field known as Urban Ecology, but I like to think of it more like Urban Nature. Here is a smattering of some natural sights I’ve been intrigued by around the city so far:

jfg

Let’s start out with the base…geology of course. Sydney is built upon a vast expanse of sandstone. Add the weathering action from the maritime climate, and this sandstone erodes into numerous cliffs that expose the natural patterning of the rock. Early Sydnians made use of the sandstone, using convict labor to carve steps into the soft rock and quarrying stone for Sydney’s elegant public buildings. (Images: grottos of eroded sandstone pockets; contrast of light rock and dark staining from running water; color patterning; color patterning)

jfg

I wouldn’t be true to myself if I wasn’t fascinated by the new plants I’ve seen here. They may be cultivated as landscape plants, but their wild beauty exists nonetheless. (Images: Fig Tree growing mass of adventitious roots; succulents growing on sandstone cliffs; Jacaranda Tree in full purple blossom, row of unidentified trees in a park)

jfg

One can’t walk around an urban park in Sydney without seeing the ubiquitous Australian Ibis. With its long curved beak and bald black head, it’s a quite different looking bird than what is common in the States. Interestingly enough, the Ibis wasn’t common in urban areas until a series of droughts in the 70’s and 80’s pushed the Ibis into the cities. Though a species native to Australia, its decline in its native habitat and rapid increase in urban areas has led to questions as to whether it’s an endangered species or a pest.

jfg

Another ubiquitous bird in the city is the Common Myna. Unlike the Ibis, the common myna is not native to Australia, and its status as a pest is unequivocal (it is recognized by the International Union for Conservation of Nature as one of the top 100 invasive species). The urban environment, however, provides the ideal habitat for these birds. Adapted to life as a scavenger in woodland environments, the features of a city—the abundant buildings for nesting, open sidewalks for foraging, and plentiful food scraps—provides an ideal home.

jfg

Ferns, being one of the most ancient types of plants, are able to thrive in harsh environments—both natural and urban. They grow wherever a crack in infrastructure provides a small foothold and traps enough moisture to drink. Here these ferns find a home similar to a sandstone cliff in the seaside dock and decaying brick wall.

The Cultural Exchange

I’m in Australia on what’s called a ‘Working Holiday’ visa. The working holiday visa program is a special arrangement between two countries that allows young residents (under 30) of one country to easily obtain a visa with working privileges to the other country. One of the goals of this visa program is to promote cultural exchange between the two participating nations by allowing up-and-coming youth to stay and work in a partner country for an extended period of time. I’m taking it as my homework to promote this cultural exchange between the United States and Australia. Though our cultures are very similar at first glance, I’ve come up with a list of things each country can learn from each other.

What the United States can learn from Australia:

- The advertised price is the price you pay. Taxes (i.e. the sales tax, or what’s called the GST General Service Tax in Australia) are included in the advertised price. No more hidden taxes or surprise charges at checkout time. It seems to be most fair that the price you see is the price you pay. As an American used to forking over just a little bit more cash when buying something, I still feel a little guilty at checkout, like I got away without paying for something.

- Get rid of the penny. I love the penny, but it’s time has come. Nowadays the penny is worth more in nostalgia than practicality. Whereas Americans enjoy advertising things for $X.99 and calculating taxes and transactions precisely down to the last penny, Australians are fine with rounding things to the nearest nickel. It’s easier that way, especially when taxes are already included in the advertised price.

Australian coinage, showcasing it’s unique fauna on the reverse sides of the coins

- Breakfast Cereal: America may be the envy of breakfast cereal variety, but the Australian cereal aisle was built for the health lover. No Froot Loops or Lucky Charms to be found in this country. Instead, Australia is famous for its health cereals, the more wheat and bran you can pack in the better. Most notable of all is Weet-Bix: the driest, most sawdust like breakfast biscuit ever engineered, but oh so tasty! Plus, in a feat of near-magic, a few Weet-Bix can absorb an entire bowl of milk.

Weet-Bix: “Every Aussie is raised a Weet-Bix Kid”

- Little cars and trucks can get the job done. You don’t need to make up for anything by driving a big truck. A compact van or flatbed sedan will work just fine to get the job done. Plus, compacts will help you maneuver into those tight Australian travel lanes. I’ve really been pleasantly surprised here in the city at how compact and efficient the vehicles are. No semi-trucks (at least in Sydney), and the biggest vehicle around is the size of an American mini-van.

What Australia can learn from the United States:

- Smoking is not healthy. So many people in Australia smoke compared to the States, and it’s not stigmatized as a lower-class activity either—in fact, most smokers seem to be wearing business casual. Whereas America has kicked its smokers to the curb, in Australia smokers have free range to roam—but as of recent they have to now be outside. Ashtrays aren’t really a thing here either. Throw your butts straight to the ground, and don’t worry because it’s someone’s job to sweep those butts up later. I would have thought that the cigarette cartons with lovely pictures of gangrenous limbs and mouth cancer would have been a deterrent to light up, but I guess not…

- Bike Culture: With terrain as flat as a Midwestern cornfield and weather as lovely as southern California, Sydney could be a biker’s paradise. Except that the bike culture is nearly non-existent here. As a biker, I’d be absolutely terrified to ride in the narrow, congested lanes of traffic—especially seeing how Sydney-ians drive. Though Sydney has converted some traffic lanes into really nice and safe bike lanes, no one seems to be using them. I’m thinking a big dose of Portland-style Bike Culture would provide the needed fix. It’s a two-way street though: the United States should take a cue from Australia and make bicycle helmet use mandatory.

Bike infrastructure in Sydney: Great when it’s there—it’s just not there in many places.

- Raincoats: With a week of Seattle winter-like weather recently behind Sydney, I’m beginning to think that people in Australia don’t know what a raincoat is. Sure Australia may be the driest inhabited continent, but it still rains here. However, the preferred choice of rain-protection seems to be massive umbrellas instead of rain jackets. A rainy day in Sydney is a hazardous place for a tall person forced to navigate the sidewalks of bobbing umbrellas bustling at perfect head-height.

- Yellow Centerline Road Stripes: All road markings in Australia are done with white lines, as opposed to America’s system of using yellow lines to separate oncoming traffic and white lines to separate traffic travelling in the same direction. Although it seems like a small detail, this is probably the most important factor in why traffic on the left-hand side of the road hasn’t seemed odd to me. With only white markings, every street in the city looks like a one-way street. I suspect this might cause some troubles when I start driving in Australia later…

I’m still ambivalent about…

- The Walk Signals: Green Walking Man and Red Stopped Man. It makes somewhat more intuitive sense than other signals—unless you’re color blind. The jury is still out on which signal is optimal. But one thing for certain is that Australian walk signals seem to favor the flow of traffic. A walk down the street results in a fair amount of time stopped at the crosswalk waiting for the signal to change, even when cross-traffic is stopped as well.

Walk. Don’t Walk.

- Australian Urinals: They are a floor-trough style with a waterfall flush. Fun to use, because it feels like I’m peeing on a wall of cascading water, but it definitely offers less privacy than single-user urinals. Also, although many urinals are flushed with reclaimed gray-water, the constant waterfall flushing still seems wasteful.

- Male and Female Toilets: The proper name of the room to relieve yourself here is the toilet—straightfoward, but less tactful than the American usage of ‘restroom’. Also, the gendered toilets are labeled by the biological sex of ‘male’ and ‘female’ instead of by the gender identities of ‘men’ and ‘women’. Biologically correct, but it seems out of sync with contemporary conversations about gender identity and restroom use.

Pick a Direction and Go with It

So what exactly led me to venture on my own to Australia? The answer isn’t quite so simple, and there’s more than just Australia that prompted the decision. Let me explain…

Ever since we are young, we are told we can be anything we want to. As young children we were asked by earnest adults to imagine what we wanted to be when we grew up. Going through high school, we took career exploration tests and were told to explore any career we could see ourselves doing. In college, we got our free range of majors, being able to even create our own major if that’s what suited us. From early on, those of us lucky enough to come from supportive backgrounds have received nothing but encouragement telling us we are able to do whatever we want to in life.

Then comes graduation. Then comes the quote/unquote “real world” where we are faced with a completely different prospect than what we’ve experienced before. Out of school and applying for a job, we may find that our chosen major is not a good fit for an employer, or that our experiences do not fit the required skills for a desired position. We may begin to experience regrets or remorse about the school or the field of study we chose after four years of scholarship; our interests—indeed ourselves—may have changed dramatically in the course of our education. Faced with uncertain prospects about the future, we may start to wonder if the decisions we made to get us to this point were the right choices to make. A little bit older and more educated now, we look with hindsight to see how our past choices have put a limit on our current prospects.

This situation prompts the genesis of the quarter-life crisis. For us who were told all along we could be anything in life we wanted, we are now finding that belief quite doesn’t hold true. Past decisions, as well-meaning as they may have been, have now limited what we can do in the future. Although we are still young and have many opportunities to change our direction, we find that such a move would require either un-doing or overlooking so much that we’ve already worked so hard to accomplish. At this juncture of our lives, we wonder if we’ve made the right choices up until now. To me, it’s this sudden realization that the world is no longer as open as we once believed that is the defining mark of the quarter-life crisis.

Maybe the quarter-life crisis is new or unique to the Millennial Generation. Maybe it just feels more pronounced now that the world is literally at our fingertips. Opportunities of what can be done tend to increase generation after generation, now seeming to reach a fever pitch in today’s society. Our culture has been breed to ‘have it all’. But having it all—having all options on the table—presents a dilemma. With so many options to choose from, our minds are unable to weigh all the pros and cons of a decision. We become intellectually burdened with the stress of not knowing which choice is the optimum one. And for some of us, the stress of not knowing which of the available options to choose can be paralyzing. This inability to make a decision in the face of limitless options is known as choice angst. Partly through graduate school and weighing my own next steps, I came upon this podcast produced by Radiolab that described the phenomenon of choice angst, https://www.wnyc.org/widgets/ondemand_player/radiolab/#file=%2Faudio%2Fxspf%2F91641%2F. I self-diagnosed myself almost immediately.

You see, as we get older, we have to make decisions in order to move on in life. And those big decisions that we have to make continually feel like they have more and more weight. Because for every decision you make—what job do I want, where do I want to live, who do I want to marry—you realize that you are closing doors on myriads of other possibilities. And those possibilities you decline could be equally as tantalizing as the ones you decide to pursue.

Thus, when I was in the course of deciding what to do after my masters program, I thought of the many different options available to me based on my particular situation. To aid in my decision, I penciled out a list of eight different directions I might go with my life. I knew that more likely than not, I’ll never get to explore all those directions that I imagined. A single lifetime is just not long enough for that. So eventually I just had to pick and direction and go with it. In the end, fruit-picking in Australia was the direction that prevailed above the others. This wasn’t necessarily because I was more interested in fruit-picking than other things, or that I felt spending time in a foreign country would benefit me more than other experiences. Rather, Australia came down to a gut decision. It really just was what needed to be done at the time.

There was no way I could have weighed out the pros and cons of every option I imagined for myself. So instead I picked a direction. And I’m going with it. Some doors may have closed because of this, but other doors will open. There’s just no seeing exactly where all this will lead.